Right: Pakistani camel herder from Gwadar in Ibri, Sultanate of Oman getting water from a Sintex tank at a large camel farm

Photographed by Manishankar Prasad in 2019

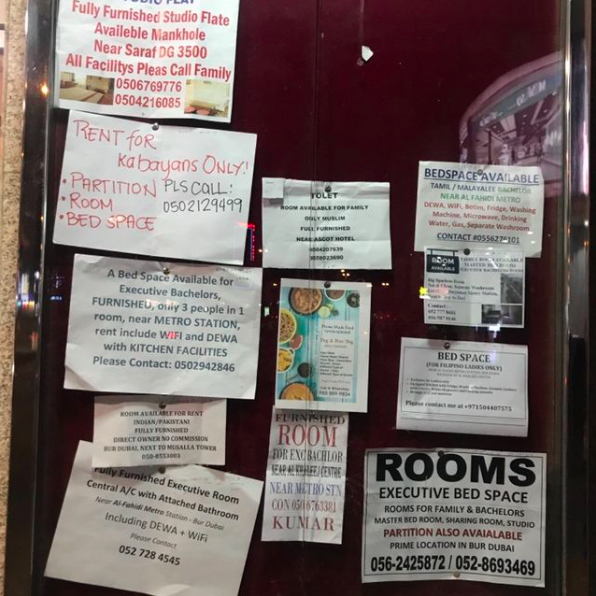

What is it that defines belonging and homeland in an era of pandemic travel restrictions and forced digital co-presence? We are publishing an essay by Manishankar Prasad, a finalist from our (no)borders open call, in which he speaks to the personal experience of being a migrant of South Asian descent in the Gulf and identity-constructing strategies such communities have there.

The pandemic has stiffened borders. Borders with a capital “B” have made their way back, impacting transnational families in a hard-hitting manner. Academic theories on globalization valorizing cross border flows are met with the reality check of entry permission denials, pre travel medical tests, and a massive loss of expatriate/migrant jobs in the light of the pandemic economic lockdown compounded by low oil prices. The migrant demographic recalibration has been underway since the 2014 oil price crash, with nationalization requirements particularly in Oman and Saudi Arabia (NitaqatNitaqatA program of Saudization that works to increase the employment of Saudi nationals in the private sector. program), which are undergoing fiscal turbulence. Lower expat numbers are front page headlines in Oman presented in a celebratory vain. These optics are however a double-edged sword, as the post-oil Gulf is moving from being an investor to being a magnet attracting investments. On the other hand, migrant fulus comes attached with people. The institutional investors may find a new asset class in response to a mega trend, however migrants come to invest their sweat equity (if not hard financial capital) and build solid communities irrespective of the residential fluidity of the region. Multi-generational migrants build economies and are cultural ambassadors of the KhaleejKhaleejKhaleej literally means “gulf” in Arabic and refers to an area that was home to many generations of migrants who were present before the discovery of oil.

wherever they are afterwards.

As a second-generation migrant in the Gulf, the passport and the visa are a reality one is born into/with. The structural transience is made evident in our daily lives in the way that a couple of suitcases from a past vacation do remain unpacked. I am unlike my parents, who came to the Gulf from Mumbai to work as academics and had a complicated relationship with the region, with an underlying clarity that they had to prepare a lifetime for retirement back “home.” They are both unhappily retired in Mumbai and regularly reminisce about their days in Oman.

My relationship like other Gulf kids is not foreclosed by borders, as borders define our existence. Our resistance against the residence permits that we renew every two years has led our imaginations to ferment alternative modes of belonging that are border agnostic. The manner in which I have attempted to “make sense” of our layered relationships with the region is through the lens of “emotional citizenship,” which triggers tangible possibilities of belonging beyond borders.

My years of “participant living” based ethnography in Muscat and Dubai with migrants who have family histories in the region since the 1960’s makes for a fascinating exploration into “post-border” resilience strategies. Many of these migrants do not know their home countries at all and are Desi KhaleejiDesi KhaleejiMulti-generational migrants of South Asian Decent. This category was formulated by the author to create a conceptual category of belonging as an anchor in contrast to the structural transience which dominates the discourse.’s who identify with the region. A good illustration of the long term community are the Hindu SindhiHindu SindhiSindhi Hindus make up a large percentage of the traditional mercantile community in Dubai.

and Kutchi Bhatia Caste BaniaKutchi Bhatia Caste BaniaKutchi Bania's of the Bhatia Caste are a mercantile caste fromthe Kutch region of present day Gujarat state with strong links to the Indian Ocean Region Trade Ecosystem.

or trader communities in Muscat and Dubai, where the Gulf is “bayt” even if they have Western passports and an Overseas Indian Citizenship card and have retained the frugal pre-oil ethos, which helps them navigate any choppy economic waters.

Top right: A laundry shop manned by migrants from Uttar Pradesh in Bur Dubai

Bottom left: A private car park next to the Al Fahidi metro station in Bur Dubai, a historic melting pot of cultures

Bottom right: This is the traditional commercial district of Ruwi in Muscat, the capital city of the Sultanate of Oman. This street is home to many migrant eateries next to the Ruwi Bus Station

Photographed by Manishankar Prasad in 2019

There is an avalanche of literature emphasizing the “rootlessness” of second and third generation South Asian or Egyptian expats/migrants who grow up in the Khaleej or the Gulf. The narratives of permanent temporality are taken for granted, as there is no etched-out pathway towards citizenship in terms of a transparent points based system in line with that of Canada or Australia. Oman and Bahrain have articulated citizenship application requirements; however, only a few hundred people have become naturalized in Oman, mainly from the Hindu Bania Community. The United Arab Emirates recently announced the possibility of Emirati citizenship for elite global scientific talent. Andrew Gardner’s book on Indian Migrants in Bahrain details that the number of expat families who have achieved Bahraini citizenship can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Photographed by Manishankar Prasad in 2019

I have worked throughout the region as a writer and have lived there for a large part of my life. I am the most at home in the region, while the country of my passport takes a bit of effort to get used to. The residency status is linked to one’s employment and the pandemic has been the final nail in the proverbial coffin when it comes to having a sense of place. I carried out ethnographic research in 2017-19 with a dozen multi-generational South Asian expats in the UAE and Oman to find out about their aspirations and their notions of belonging in the region. During the pandemic, while I was stuck in Pune in the light of denial of entry permissions, I felt helpless; however, I continued the research through digital ethnographic modes which sowed the seeds for conceptualizing digital emotionality. As a second generation KharjeeKharjeeArabic term for "expatriate", I worked with a similar third generation Indian Bania businessman in Muscat while helping him to make the move to digital, which gave me a front row seat into the deep connection that multi-generational migrants have in the region, despite the economic air-pocket that they are currently experiencing. Borders do not hinder me in creating post-structural spaces for the articulation of belonging in an era of being remote.

My research participants were completely raised in the region and two of them were specifically born in the UAE. Three decades of living in the region does not provide them the sense of deep belonging; the Sword of Damocles is dangling over their heads, as their visas are linked to their jobs. The sense that I got from my conversations is a vibe of despondency about ultimately packing up and going to a place that is alien, whether it is South Asia or the West. One South Asian male respondent was expressing his disappointment at spending a ton of money reading his undergraduate science degree at a premier university in the UAE. In the unofficial caste system of the Gulf, a local degree and a South Asian passport will fetch one a lower pay than a fresh graduate who is a Western degree recipient on an OECD passport. Since the pandemic hit, my interview respondents have been planning their paperwork for Canada.

Scions of business families have it easier, as they hold investor visas that are more stable although these are also connected to a renewal every two years, which is subject to ownership and shareholder documentation. UAE, as usual, is the first mover in the region, as it has rolled out a permanent residency scheme for prominent businessmen and their families known as the “Golden Visa.” This scheme is by invitation and is specifically targeted for members of the power elite within the expat community.

Theorizing belonging for the middle class and affluent expat/migrant community has been framed by Indian American Migration Academic Prof. Neha Vora as “consumer citizenship” in her seminal book, Impossible Citizens, where the money spent in the local economy builds ties of belonging. I would like to (re)frame our notion of belonging in a visceral sense, an emotional connect with the region. I grew up singing the Royal Anthem and celebrating the Omani National Day with more fervour than my passport country’s Independence Day. This “emotional citizenship” does not evaporate even when we are overseas in our countries of origin, as we follow local news on Twitter and are connected to the everyday in the closest manner. “Emotional citizenship” as a new analytical category is sans expectations of acceptance in our adopted lands, which take the form of “temporary cities” (in the words of urban theorist Yasser Elseshtawy), built by millions of migrant laborers who received an opportunity to financially support families back home.

Right: A barber shop in Bur Dubai run by men from Lucknow and Dhaka. The salon doubles up as a space for conversation in a transient city

Photographed by Manishankar Prasad in 2019

In a post pandemic era, many thousands will head back home, some will hope to return as and when the situation improves. But these families will carry Dubai, Muscat, or Manama in their hearts, as the “bayt” will always be the Gulf. The reality is that even when migrants/expats retire and head back to their countries of origin or the West, they never feel comfortable and they long for the good old days. These emotions are barely taken into account in academic studies regarding identity and belonging in the Gulf. The region was a land of opportunity for their parents, but their children made the region theirs own. Every region has its flipside, however most research on the region focuses on its negative aspects, especially the Kafala systemKafala systemThe system of expatriate labor governance in the Gulf that ties the fate of the employee to a single local employer, considered by many to be restrictive in regard to human rights.. The region also presented many lives with the resources to live better when our passport countries failed our families. The post-pandemic Gulf will need its migrants, albeit in fewer numbers, but it will be home for me always. The shwarma and mint shai at Turkish House Restaurant in Al Khuwair, Muscat, the neighborhood in which I was raised, is an indelible memory that no border can erase.

Instagram has emerged as a site of curating a sense of everyday belonging, as I have followed my favorite places for hanging out over the weekend in Dubai, such as Jameel Arts Centre, the contemporary art gallery in Dubai, or the mobile first exhibition at NYU Abu Dhabi. The ability to follow the developments was a reassuring anchor of continuity, as the body was in the passport country but the mind was in the Karak Chai shops in Mina Bazar, Bur Dubai.

On a personal level, as a writer my creative practice is influenced by my positionality as a “Desi Khaleeji.” As I write this article, my hope is the narrative on the Gulf migration moves beyond the pathos of borders as a limiting instrument.