Viewed on a historical scale, borders are in a state of constant change: lands merge and split, gates are set up and taken down. Borders function in a state of simultaneity; they are often ghostlike, intangible and yet more real than real. What is the function and meaning of borders? Which borders are benign and which are malign? How can one cross both real and imaginary borders? Who sets these borders in place and why? Is it possible to live in a world without borders? How do humans and non-humans live within and without borders?

For our (no)borders issue we consider these vital yet tricky questions. To begin the conversation, we've asked the finalists of our open call to briefly reflect on borders by describing some personal memories of their encounters with them.

YIANNIS CHRISTIDIS

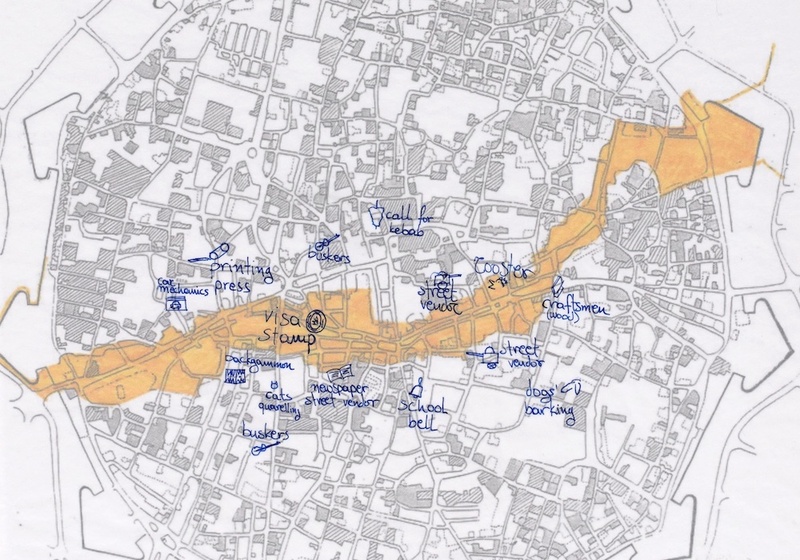

Assistant professor, sound researcher, lives in Cyprus

Are borders human-made constructions defining in vain a temporary ownership? Or rather contested reference lines facilitating a formal normality among and between entities? To me, borders seem to constitute absurd, both spatial and conceptual instruments enabling the hegemony to constrain, maintain, and enforce its power. Several times I had to cross such structures, while conducting ethnographic research in the divided city centre of Nicosia, Cyprus. As the limits of the northern and southern parts of the area are defined by the borders of a third (non)space, it feels that it is us, people, who violently confirm our fluidity and transitory beingness, by forcefully placing a pausal stage in our everyday activity. In the North, most residents are Turkish Cypriots, while the South is inhabited by Greek Cypriots. In order to cross, I had to stop by the checkpoint. And every time, a paradox hybrid feeling of being searched, observed, objectified, and un-named was emerging. Showing my identification papers, being checked, receiving the permission to pass—all of these make up a robotic process that perfectly fits the existing de-humanized context.

Over the land, though, sound ignores borders. I observed and recorded loud sounds from one space travelling freely to the other and vice versa. I also observed the people crossing with me. Workers, tourists, visitors: the sound of their footsteps, talks, sometimes laughter or a phone call compose the human transgressive resonating presence. Consistent microsonic qualities which form constant trajectories, messengers of life and border discourse to the other side.

The aural similarities and differences at both sides, alongside the (non)space in between, confirm, to my perception, that borders constitute forceful representations of authority. While they are believed to define and maintain history, I personally see them as planted assemblies which define policies, but worst of all, less privileged peoples’ lives.

Architect, historian, curator, and assistant professor at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft)

In Brazil, 120 kilometers from the bridge over the Araguaia River, Marabá is the most populated city on the banks of the Transamazônica Highway, a military-led project cutting through the Amazon rainforest, literally paving the way for its colonization in the 1970s. In the heart of the Industrial District of Marabá lies the Carajás Railroad (EFC), operated by the now privatized Vale do Rio Doce. Ten companies settled there in the 1980s to establish a hub to transform ore from Serra dos Carajás into pig iron, the raw material for steel production. This is when I moved to the settlement with my family. My father, then an engineer in his late-twenties, was offered a promotion to relocate with his young family, appointed to work on the town’s construction for a Rio de Janeiro-based contractor. I was four years old and my sister was three when we first arrived; I was six when we returned to Rio, my hometown.

As if I had crossed a border of Eden, this was the most intimate contact that I have ever had with a still raw and yet to be domesticated nature, but not just with any forestland: with the “forest of the forests.” I am unsure as to whether the grandiosity that characterized that overall environment refers to my own scale back then. Or perhaps it refers to the magnificence of nature—both flora and fauna—including gigantic trees and hanging vines with which my sister and I, and even my parents, were amazed to play with. Or to the attempt to control it that was underway: new construction, a town being built from scratch, huge glades, a lot of mud, and scared and desperate animals crossing newly paved highways, often being captured or tragically hit. It goes without saying that such big extractive and infrastructure projects have historically been implemented worldwide, and in Brazil in particular, to the detriment of biodiversity and indigenous peoples. During our stay in Carajás I undertook my first trip to Brasília, which—as I became an architect and scholar dedicated to the work of Brazilian modernism, Oscar Niemeyer, and his collaborators—I will also never forget. Lucio Costa’s monumental axis punctuated by Niemeyer’s purist palaces contrasted greatly with my own Transamazônica reality. Both developmentalist projects of modernity and modernization are, nevertheless, completely interrelated.

Architect and photographer, Doctoral Fellow of the Institute for History and Theory of Architecture (gta) / ETH Zurich, based in Zurich and São Paulo

Most of my experience crossing borders happened in the free trade zone between the European Union and Switzerland. While products, currencies, European nationals, and wild animals come and go every day, humans from the so-called ‘third-world’ like myself get generally recognized, stopped, scanned, and interviewed on either side of the border. While this is most of the time just a minor hassle for someone with a visa, it is a protocol reminder that a foreigner will never belong or be fully “integrated.”

As an architect and photographer, I enjoy the argument of Ariella Azoulay that the photographic camera redefines the lines of belonging and forges a new citizenship beyond borders: “Against the political order of the nation-state, photography (...) paved the way for universal citizenship: not a state, but a citizenry, a virtual citizenry, in potential, with the civil contract of photography as its organizing framework. Citizenship in the citizenry of photography asks not to be stopped at borders and plays a vital political role in making sure other cultures are accessible, in all of their prestige or misery, deeming local cultures to be worthy of documentation and public display.” As such, rather than a citizen of any specific nation, I see myself as a citizen of images, a collective world open to all.

Artist and researcher, based in Istanbul

17/12/20—A Territory Surfaces

A late arrival, fall was thick the past two weeks. A concentrated dryness drowned everything in hues of brown and yellow as the leaves separated themselves from the trees and, for a long moment, joined the horizontal plane of the ground. In time, they’ll re-join the vertical flow through a passage into the subsurface and enter the tunnels hidden behind tree barks—a tangled web of differentiations, a slow guessing game of interiors and exteriors. Perhaps next spring, what’s below will be above—will I be able to tell the difference? But, for now, the leaves function as a unifying surface on a scale that my eyes impose. From my previous trips to the woods, I know that there is a stream in front of me with a 5-liter plastic bottle stuck in it and that I’m sitting next to a fallen tree, but the contours of my surroundings, the ends and the beginnings, disappear under the blanket of yellow, brown, and green patches. This stable invisibility, hiding insects, mud, and all the other existents that threaten my body’s boundaries and smoothness, gives me comfort. The dryness of the leaves carry the potential of a rustle, a signal that announces the arrival of trespassers. I rest settled, knowing that my temporary territory is safe and sound. How easy it would be, I think to myself, to draw the surface I see, and how challenging and unsettling it is to imagine everything hidden beneath.

Curator, based in Paris

The dying person is in the situation of a human who leaves his home without the key and can no longer enter because the closed door opens only from the inside.

Vladimir Jankélévitch

This happened to me during a trip from Paris to St. Petersburg to visit my family. On my way back I stopped by Helsinki. I had a friend there to visit, Finnish artist Nina Ross, and when my plane arrived I was—for the first time in my life— the first person in the queue to the check desk. I gave my Azerbaijani passport to the most pale-blue-eyed and blond person I had ever seen . . . and we started an hour-long conversation in which the question if I was Syrian or not was repeated at least fifty times. Further on, the question “Are you Syrian?” would always be coming back in between two or three other questions about why I was entering Europe. After half an hour, another employee was called to join and ask me the same questions all over again. Before he appeared, we were waiting for him, and I had the time to talk with friendly passengers waiting behind me. The border officer then shouted at me saying that I lied because I was not “traveling alone.” He was screaming, turned mad by his own role and his own repetitive questions . . . when a third employee asked me if I was Syrian I decided to stop speaking English, switched to French, and stopped answering, getting mad myself, calling them racist, losing control too. I felt blocked for no reason by the European border, not allowed to go back.

PhD student, based in Singapore

It is paradoxical, but the idea of belonging to the nation is often conceptualized from being the outsider or being the “other.” I grew up in the Sultanate of Oman as a “Desi Khaleeji,”“Desi Khaleeji,”South Asians who feel at home in the Gulf or the Khaleej where my parents were educators. My awareness of borders was carved early in life at passport controls, where I was often asked curtly by the immigration officer, why did I want to travel alone at such an early age? It was the mid 1990s, and overseas travel to the Gulf was not perceived as emancipatory vis-a-vis travel to the West from India. At passport control in the Gulf, I saw that the indigo blue passport was not being held in high esteem, although this has dramatically evolved in the Modi era, with increasing close relations with the GCC Sheikhs, Emirs, and Sultans. These experiences either shaped one’s understanding of the borders in a forked manner as it makes one more aware of the sense of being an outsider and strengthens the national identity or it makes one run for a passport with greater travelling power. For me, the sense of being a brown man was reinforced every time I faced racist or discriminatory taunts and this othering reinforced my commitment to maintaining my indigo blue passport, even though I have lived overseas in the Gulf and South East Asia for most of my life.

Borders are “om(an)ipresent” and define my actions/activities in the everyday towards navigating them subconsciously in a manner to make them irrelevant through the Weapons of the Weak approach (invoking James C. Scott’s seminal work).

London-based art historian and doctoral student

Born soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall, my childhood overlapped with some of the most seismic political events of the late twentieth century which included two that most affected my Yugoslav-Georgian family—the almost simultaneous dissolution of the USSR and Yugoslavia. As my Serbian grandparents were being evacuated from Kosovo in 1998, ethnically Georgian refugees were fleeing the war-torn Abkhazia. I came to regard borders as fragile and fluid entities that could be re-negotiated or re-imagined, for good or for bad, at any moment in history, rather than physical and symbolic boundaries that protect citizens and define where one state’s sovereignty begins and another’s ends.

Liberals of Western Europe, where I now reside, extol the principles of the free movement made possible by the frictionless borders of the European Union. Whilst open to the members of its own club, opportunities afforded by the soft borders of the EU remain an unattainable dream for hundreds of thousands of refugees who embark on treacherous journeys to a new life in Europe. This “openness” is therefore contingent on the “hardness” of the EU’s external borders with countries such as Russia or Turkey. A report I recently came across stated that since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, European countries have built or started building 1,200 km of anti-migrant fences, which is equivalent to the distance between Paris and Vienna. Whilst Trump’s Wall has received wide coverage internationally, perhaps less talked about were Europe’s anti-refugee fencing projects of 2015, the first of which was the razor-wire fence constructed by Hungary on the border with Serbia. The bitter irony is that in 1988 Hungary was the first Eastern Bloc country to dismantle its fortified border with a Western-aligned country. Many historians believe that the opening of its border with Austria set in motion a chain reaction which led to the end of the Cold War.

Anthropologist, student at the University of Tartu, lives in Helsinki

In the past, I often used to visit my grandfather near Zelenogorsk. To get to his house, one had to take a long train ride from the Finland Station, then change to a bus, get off at the 21st kilometer near a former military settlement with holes in its walls, and from there—to walk forty more minutes through the woods to a small farm that my grandfather had moved to in the 1990s. On the way to the dacha, the forest was full of abandoned military fortifications: there used to be a Finnish and later a Soviet military training ground. When I was a child, I thought the ground with its numerous empty cartridges, forest bunkers, trenches, and hangars were the remnants of the old Finnish border. The border-zone, which in fact used to be closer to Saint Petersburg, was perceived almost like a space of its own, a specific territory. Demolished buildings, war debris, and barbed wire lines appeared as a part of the vast landscape of half-abandoned ruins that caused fear and anxiety. But also—as a hope for an accidental discovery that would enrich and relieve me of the need to take any effort later in my life.

Now I am living a quiet life in Helsinki and returning home to Russia does not seem the easiest thing to do, I really miss this old “border” rubbish and disorder, which enables me to rethink stories related to the impact of different boundaries on human capabilities.

Artist working with sculpture, video, and text, based in Los Angeles and Belarus

In the summer of 2016, I was visiting a friend in Berlin. On my last day there we went to the flea market; I got a postcard circa 1942 and some GDR stamps depicting Engels. We had a late night and the following morning I slept through my alarm and missed the flight to London. As I was looking up alternate tickets I discovered that one could also get to London by taking the bus. I thought it was quite sweet that one could take a bus to an island. (I feel like there is a joke or a marketing ploy in there, e.g.: “Want to go to a ________ (faraway place?) Just take the bus!”)

I did, and the bus started making its way through Europe. There were no border checks—so the way I knew which country I was passing was by seeing the mobile provider change in the upper right corner of my phone and by receiving a text message welcoming me to the said country and informing me how much texting/data/calling would cost. After about twenty hours the bus got on the ferry to cross the English Channel. I remember a 1970’s-style lounge in orange hues and standing outside in the night looking at the water—but that could also be a memory from a different ferry and a different year. Only the mobile provider would have the precise information on the time and location; but not on the hue or the style of the lounge (I think? I hope.)