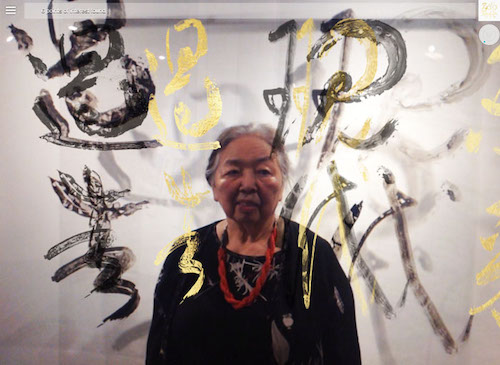

By Tamiko Thiel, with original music by Ping Jin

Video walkthrough of the interactive virtual reality large projection installation

Version 2017, recorded from screen in 2021

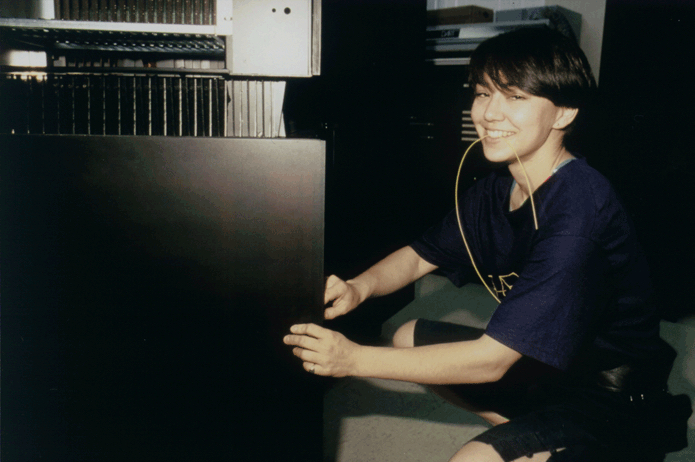

Tamiko Thiel’s career started with a breakthrough: she was responsible for the game-changing design of a supercomputer that influenced Steve Jobs and is now a part of MoMA’s collection. Soon after, she turned to art, pioneering the use of 3D graphics as well as augmented and virtual reality.

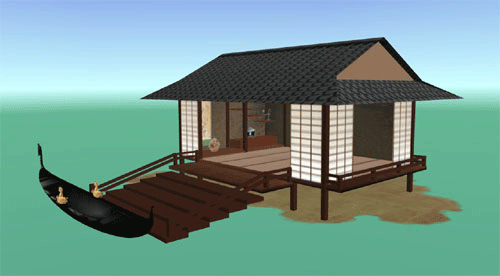

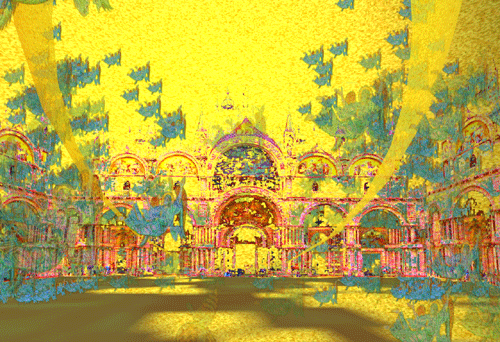

For EastEast, Tamiko Thiel has recorded a new walkthrough of her VR piece, The Travels of Mariko Horo. In it, a time-traveling Japanese woman crosses the borders between the 12th and the 21st centuries, exploring and constructing the exotic and unknowable Occident, in which Byzantine and Venetian imagery collides with Shintoist and Buddhist patterns, and Dante’s Christian universe is seen through the lens of Buddhist cosmology. Tamiko Thiel told our Senior Editor Lesia Prokopenko about her work, her mixed background, and the reality of the virtual.

, where the mouse and windowing system were invented. There were also people from Apple: my best girlfriend told me later that she was on the secret team to design the Macintosh. It was all very intriguing, but it didn’t fit in with my personal interests. So I decided to go to MIT and look for something more exciting. I was in the mechanical engineering department there, but friends from Xerox PARC gave me introductions to the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab, Marvin MinskyMarvin MinskyMarvin Lee Minsky (1927–2016) was an American mathematician and computer scientist concerned largely with research of artificial intelligence. He is the author of Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines (Prentice-Hall, 1967), The Society of Mind (1986) The Emotion Machine: Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the Human Mind (2006).

and his graduate student Danny HillisDanny HillisWilliam Daniel “Danny” Hillis is an American inventor, scientist, author and engineer, as well as the founder of Thinking Machines Corporation, a parallel supercomputer manufacturer. He is currently best known for inventing the 10,000 Year Сlock, which he is building with his Long Now Foundation.

. Danny and I really hit it off, we became great friends. And it just turned out that most of my friends at MIT were at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab. I didn't study AI, they just had the best parties! For the first year, I went ahead with my mechanical engineering degree. And after that, I had all the requirements completed. So I could take whatever classes I wanted, and I discovered what would become the Media Lab after I graduated. They were teaching computer graphics and using computers as tools to deal with visual issues as well as with cultural and social ones. When I discovered that, I decided that I wanted to become a media artist.

After I graduated I was going to look for an art school when Danny Hillis pounced on me and said he was about to start a company to really build the Connection Machine that he was designing as his PhD thesis. He asked, “Could you give the Connection Machine a form that will really convince people this is a completely new machine, like nothing they’ve ever seen before? This is the future of computing.” We were both about twenty five and then a whole lot of people on the team were even younger, they had just got their bachelor’s, like Brewster KahleBrewster KahleBrewster Lurton Kahle is an American inventor, philantropist, and digital librarian. He is an advocate of universal access to all knowledge. Kahle founded the Internet Archive that offers 85 billion pieces of deep Web geology., who went on to create the Internet Archive—he did the chip design for the Connection Machine. So it was a really young company, confronting the old men who had been creating machines like the CrayCrayCray Inc., a subsidiary of Hewlett Packard Enterprise, is an American supercomputer manufacturer headquartered in Seattle, Washington.

or other supercomputers of the time, which were number crunchers. They would have at the most a couple of processors, but could do calculations very, very quickly. Danny’s designs were completely different: with 64,000 small one-bit processors that worked slowly, but simultaneously, so they all do the same calculation on different data points at one time.

This was before big data. Brewster Kahle might’ve even been the guy who invented the term big data, because he was always interested in huge amounts of data. But that was not the way people thought or worked and not the way computers worked. Back in the mid 80s, for most people, it was inconceivable that the internet would ever contain so much data, that data-intensive computing would even be interesting. So the company and the machine were really revolutionary at the time. Sergey Brin, who co-founded Google, learned parallel programming on the Connection Machine as an undergrad—he really took that programming paradigm that Danny Hillis and the other scientists developed, and applied it to the server farms that Google is now famous for. This technology is what has enabled artificial intelligence to be the breakout technology of our time.

Below (color): Connection Machine-2 and DataVault mass storage device

Below (black & white): Connection Machine-1

The structure looks like eight cubes plugged into each other, and really spoke about the CM’s internal routing network designed by Nobel physicist Richard Feynman, who was our big hero and worked with us during his summer vacation. So basically, I played around with his description and his sketches, and eventually was able to really change them spatially: he could draw them up to the fourth dimension, but I had to draw up to the twelfth dimension. I wrote about this in my article on the design of the Connecting Machine. We didn’t have 3D computer graphic design tools at that point—we were doing everything on paper. But I was able to come up with a way of depicting that structure, so I could repeat it endlessly.

The blinking of the lights coming through the translucent doors essentially shows you the machine “thinking,” shows the internal workings of the software running through its computations. And of course, with a computer, that’s the important thing, not the size, not the shape, but really, you know how the software works internally. So that was my first professional artwork. Of course I was really delighted when, thirty years later, the Museum of Modern Art in New York took it into its collection!

I created The Travels of Mariko Horo as a reflection on Christianity versus Japanese Shintoism and Buddhism. When I came to Catholic Bavaria I encountered all the Catholic saints, the corner niche of a building with a sculpture of Maria built into it, or at some crossing in the middle of nowhere there will be a Christ on the cross because someone died there in a car accident. And when you go to Upper Bavaria, many houses have some sort of painting on the wall, images of St. Florian to protect them from fire or some sort of indication of the Catholic faith. My Japanese grandfather converted to become a Methodist minister, so in America I grew up in a Protestant culture, which is really very abstract, there’s a cross but no Jesus hanging on the cross. When I arrived in Catholic Europe, I realized it was like Asia—like Japan, where in some little tiny niche, there’ll be a little temple with some Buddhist figures, and there’ll be ropes tied around a rock or a tree to mark them as being sacred. These are all animistic beliefs that underlie all the older world religions. I recognized this world in the Greek and Roman myths I loved to read as a child—and then later in Catholic Europe, where this older animist past was covered by a thin veil of Christian imagery.

In The Travels of Mariko Horo I was looking at Europe, specifically at Venice, from the viewpoint of an Asian steeped in Buddhism and Shintoism. There is an entire genre of Japanese pre-modern art imagining foreigners and foreign lands, and I took that as my point of departure for Mariko Horo, my time-traveling fictitious alter ego. She creates the exotic West in her imagination, interpreting Western art images with a worldview shaped by Buddhism and Shintoism.

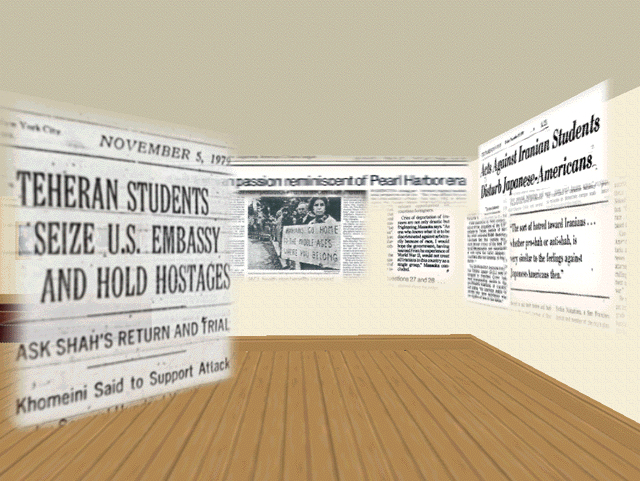

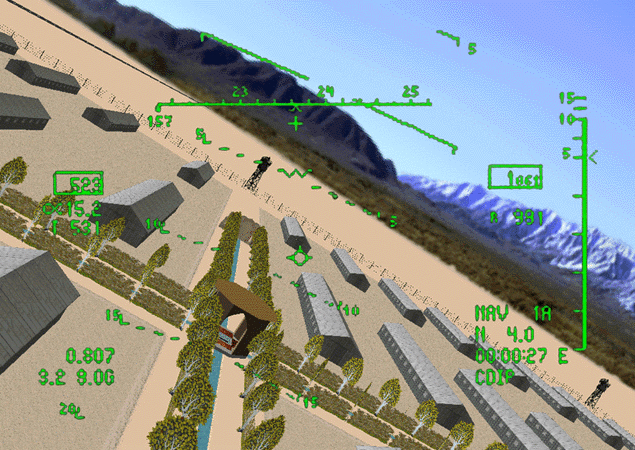

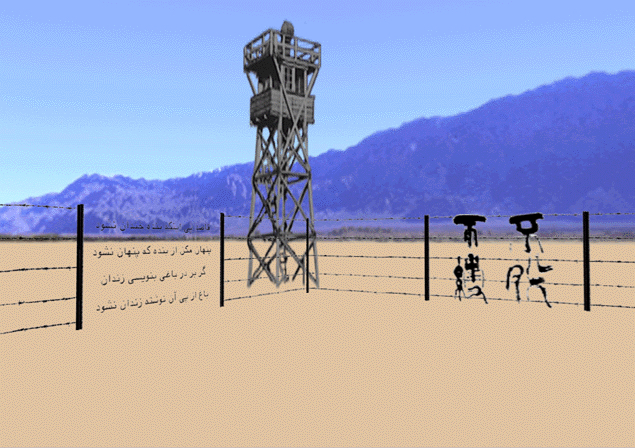

With the VR technology that all of a sudden was in my hands, I first thought I could use this to simulate video installations that were too complex and expensive for me to implement with real video equipment. It turned out it was still too early to do that, but with VR, I had no spatial restrictions. The first art project of my own that came out of that was Beyond Manzanar, completed in collaboration with Zara Houshmand, in which I created a simulation of a part of the Manzanar Incarceration camp where 10,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned without trial solely on the basis of their ancestry in World War II. We then overlaid the camp with surreal elements of Japanese culture and the historical incarceration, together with elements of Iranian culture and the threat of mass incarceration that Iranian Americans had faced in 1979-1980 during the Iranian Hostage Crisis. Virtual reality was a way for me to create huge virtual worlds that couldn’t exist otherwise, enriched with layers of cultural, political, social meaning and commentary.

My German American father was a professor of architecture and urban planning, so I grew up with him talking about the wonders of European city planning and of Japanese stroll gardens. In the stroll gardens you turn a corner, and all of a sudden you see a completely different vista that you hadn’t expected. I was always hearing about the design of space and the experience of sequences of spaces. The work of my father’s is really the theory that I use to create virtual worlds, and also the theory I use when I teach about creating virtual worlds. Merging the real and the virtual is what I’m interested in.

I started doing AR in 2010. A friend who also did VR, Mark Skwarek, invited me to participate in an AR intervention he was organizing at MoMA New York—without their knowledge or approval. I was totally jazzed when I realized that I could create site-specific works in AR without having to re-create the entire site first, as I had to do in my “site-specific VR” artwork. The next year I led our intervention into the 2011 Venice Biennale, the two interventions were recorded in several books to become part of the media art canon—and we were all off and running as AR artists!

LP: What about the cohabitation of the technological and the biological? In recent years, your works have been dealing a lot with ecological issues—the way species and environments mutate (Gardens of the Anthropocene, Wild Gardens, Unexpected Growth, Evolution of Fish, etc).

TT: Ecological issues crept into my AR practice very early, starting in 2011 with Newtown Creek (oil spill), a piece about the extremely polluted river that forms part of the border between the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens. It runs through areas that have become very expensive real estate, but there is almost no access to it and many residents don’t really realize it is there. I slowly started realizing that climate change was a serious issue (helped by my artist friend Mechthild Schmidt-Feist, with whom I would stay in New York and who drummed into me how awful the situation was already). I started “mutating” plants, flowers, algae into science fiction scenarios to “visualize” a nature out of control, a nature that started fighting back against the destruction that humans are wreaking on the ecosphere. Especially with an invisible art form like AR, which the users have to actively install on their smartphones to see at all, I felt I had to provide a positive inducement for users to view my works. So I create beautiful scenes that lure users into viewing the work, and then when they look more closely the works reveal the dystopian destruction of ecosystems.

Additionally through my Japanese background, I see flowers and plants as sculpture, and I love to be able to create these forms that are somewhere between realistic and abstract—computer graphic ikebana in some sense, the Japanese art of flower arranging. The human or animal form is so much more demanding, but with my science fiction plant scenarios I have full artistic freedom!