Miniature from Miraj Nameh manuscript, 1436

Turc 190 / Bibliothèque nationale de France

During the night of the 27th day of the month of Rajab, the angel Jibreel woke up the prophet Muhammad and sent him on a night journey (Isra) to Jerusalem, followed by the ascent (Mi’raj) to heaven, where the prophet met other prophets, angels, and Allah, and then visited hell. This story has inspired Islamic writers and artists for centuries and was perhaps most vividly captured in 1436–1437, when the youngest son of Timur (Tamerlane), Shah Rukh, who became the ruler of the Timurid EmpireTimurid EmpireDuring its heyday it included today’s Iran, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Afghanistan, most of Central Asia, as well as parts of modern Pakistan and Syria. after a short, internecine war and the death of his father, ordered The Book of the Ascension (Miraj Nameh). The illustrated manuscript was made in Herat (a city on the territory of today’s Afghanistan) and by the end of the 15th–early 16th century ended up in Istanbul in the library of the Topkapi Palace. In 1672, at the modest price of twenty five piastres, it was purchased by Antoine GallandAntoine GallandChristiane Gruber, The Timurid Book of Ascension (Miʿrājnama): A Study of Text and Image in a Pan-Asian Context, Valencia, Spain, 2008.

, who would later become famous as a translator of One Thousand and One Nights.

At the time of the purchase, Galland was in the service of the French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Charles-Marie-François Olier, marquis de Nointel and, among other things, was responsible for searching for and acquiring books, coins, and antiques. During his trips, Galland spent more than ten years in the Ottoman Empire and the Levant, received the official title of Antiquarian King, and took part in the compilation of the Oriental Library—a monumental encyclopedia of the East, which he completed after the death of its main author Barthélemy d'Herbelot. Galland translated from Arabic, Turkish, and Farsi, kept diaries, and towards the end of his life was appointed the Chair of Arabic at College de France.

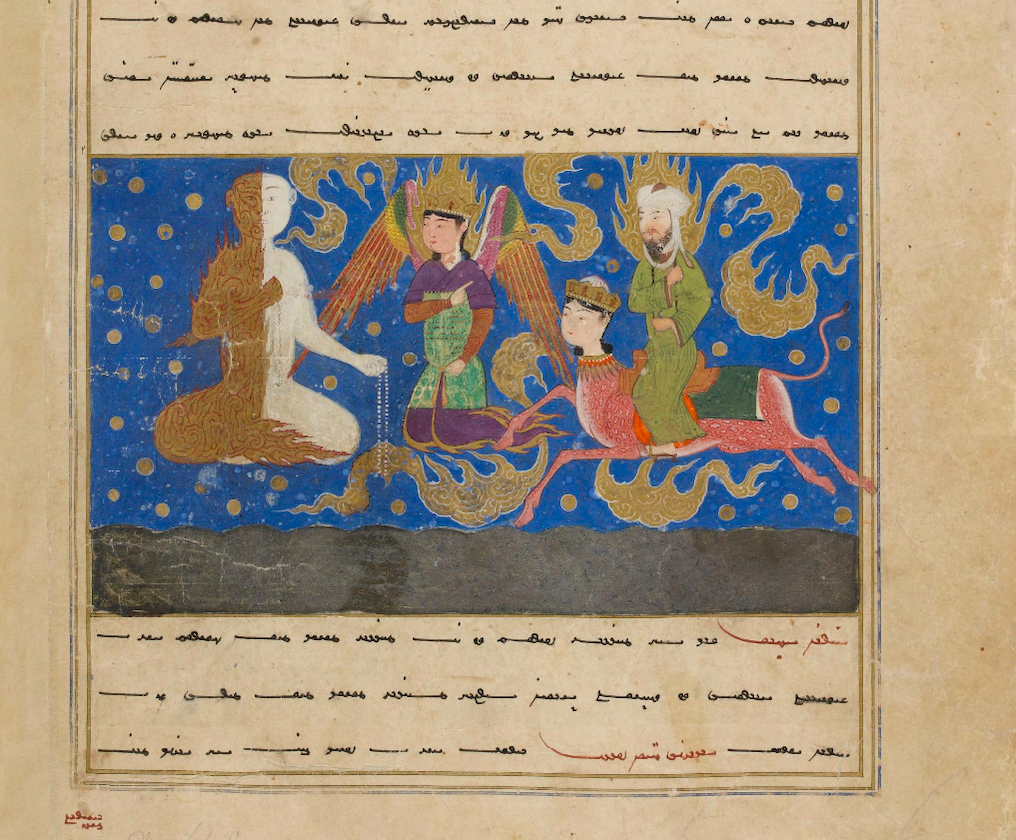

Folio 11r: “...I saw a white rooster. Its head was below the throne [of God] and its feet were firmly gripping the earth. I asked Gabriel: ‘What is this rooster?’ Gabriel answered: ‘This rooster is an angel that counts the hours of the day and the night. When prayer time arrives, he cries out and recites a tasbih. Upon hearing its voice, the earthly roosters also cry out and recite a tasbih.”

Folio 11v: “...I saw an angel, half of which was made of fire and the other half of snow. I asked Gabriel: ‘What is this angel?’ Gabriel answered: ‘This is the angel whose voice is so booming that, when it recites a tasbih, men say that it thunders.’ It held two rosaries in its hands.”

Folio 15r: “...and I saw an angel with seventy heads. On each head there were seventy tongues, each of which recited seventy different kinds of tasbihs.”

Folio 22v: “...I reached a sea of fire. Gabriel said: ‘On the Day of Resurrection, this sea of fire will be thrown into hell, and the inhabitants of hell will be tortured by this fire.”

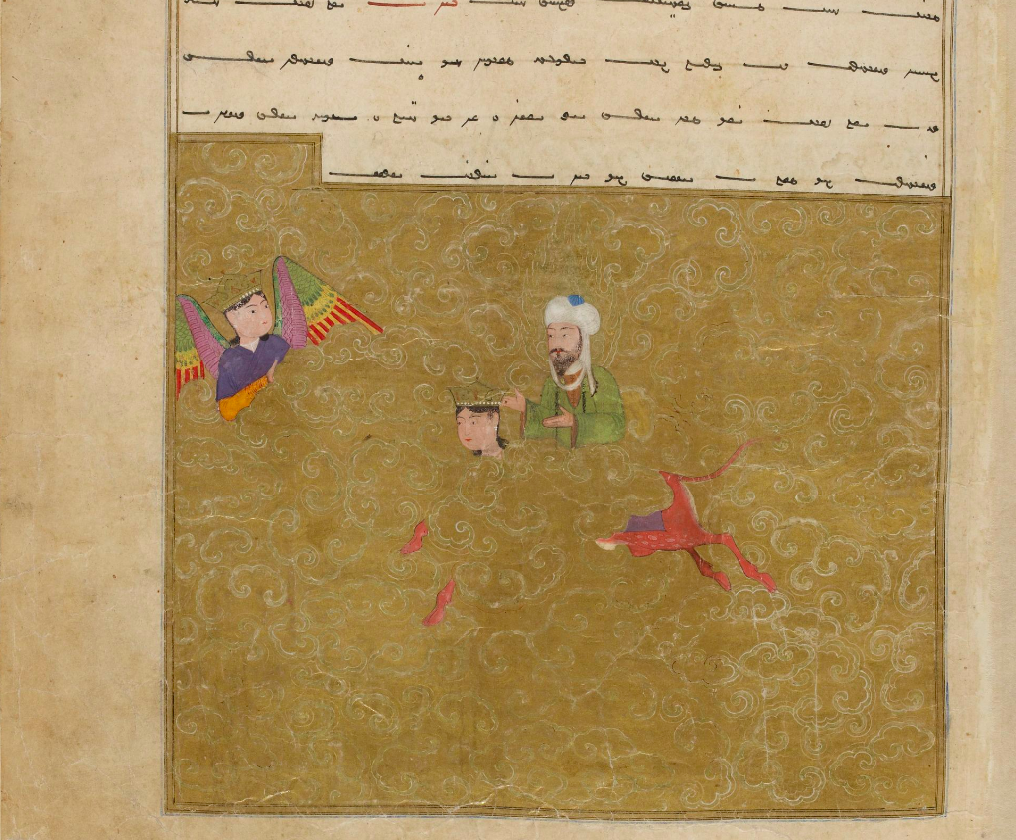

Folio 28r: “...That heaven was made of light (nur). There did not remain an empty spot the size of a house [because] the angels were filling it up completely.”

Folio 32r: “...I saw a large angel [with] seventy heads, whose size equaled this world. On every head there were seventy tongues. Day and night, it recited a tasbih to the Lord Most High. Next to it was an angel that was so large that if one were to place all the earth’s seas onto its eye, they would not reach the other eye.”

Folio 36v: “Then Gabriel said: ‘Oh Muhammad, now go to the station of proximity and prostrate yourself.’ When I arrived at the station of proximity and prostrated myself, I saw the Lord Most High with the eye of my heart.”

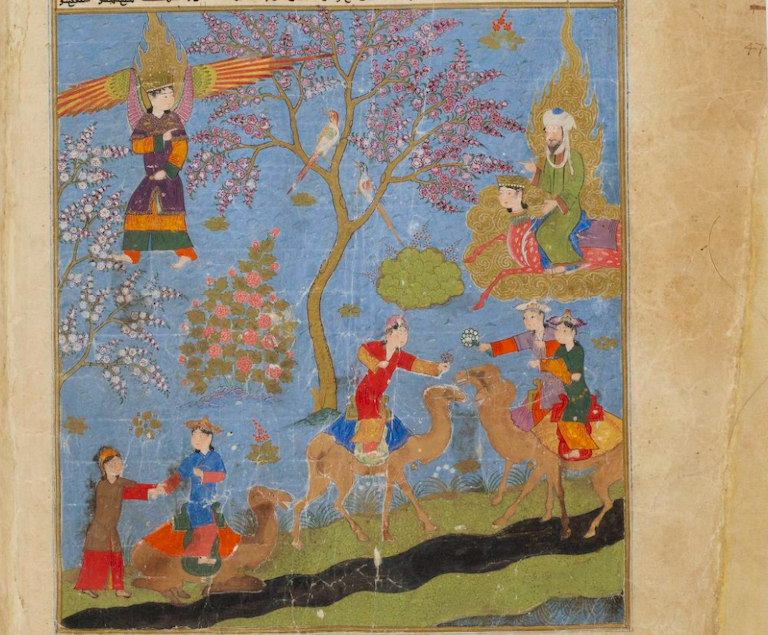

Folio 49v: “The Lord Most High created [paradise] for my communities. In a garden, I saw many huris, some of whom were sitting on chairs, and some of whom were holding each other’s hands and were playing. Birds were coming toward them and sitting atop those huris’ heads. On Fridays, they rode camels to visit one another and they went laughing and playing. Then they greeted one another.”

The acquisition of Miraj Nameh was an ordinary episode in his biography and we can trace the further fate of this amazing artifact: in 1675, Ambassador Nointel presented the manuscript to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Minister of Finance and de facto head of the Louis XIV government, who was a collector of an extensive library that in 1732 became part of the Royal Library—the predecessor of the National Library of France, where the manuscript has been kept to this day.

According to the inventory of the 17th century, sixty of the sixty four miniatures have survived up to today. It is noteworthy that the manuscript is written in Chagatai (Chagatai Turki or Old Uzbek) using the Uyghur script. Due to these circumstances, it was not possible to decipher the text until the 19th century, when Jean-Pierre Abel-Remusat—a French sinologist and curator of Orientalist manuscripts of the Royal Library—managed to translate a few fragments. Half a century later, Abel Pavet de Courteille, another orientalist specializing in the study of Turkish languages, transcribed the whole text into Arabic script and published it with French translation in 1882. Today researchers recognize Timurid Miraj Nameh as unique evidence of the Timurid Empire’s flourishing book culture.

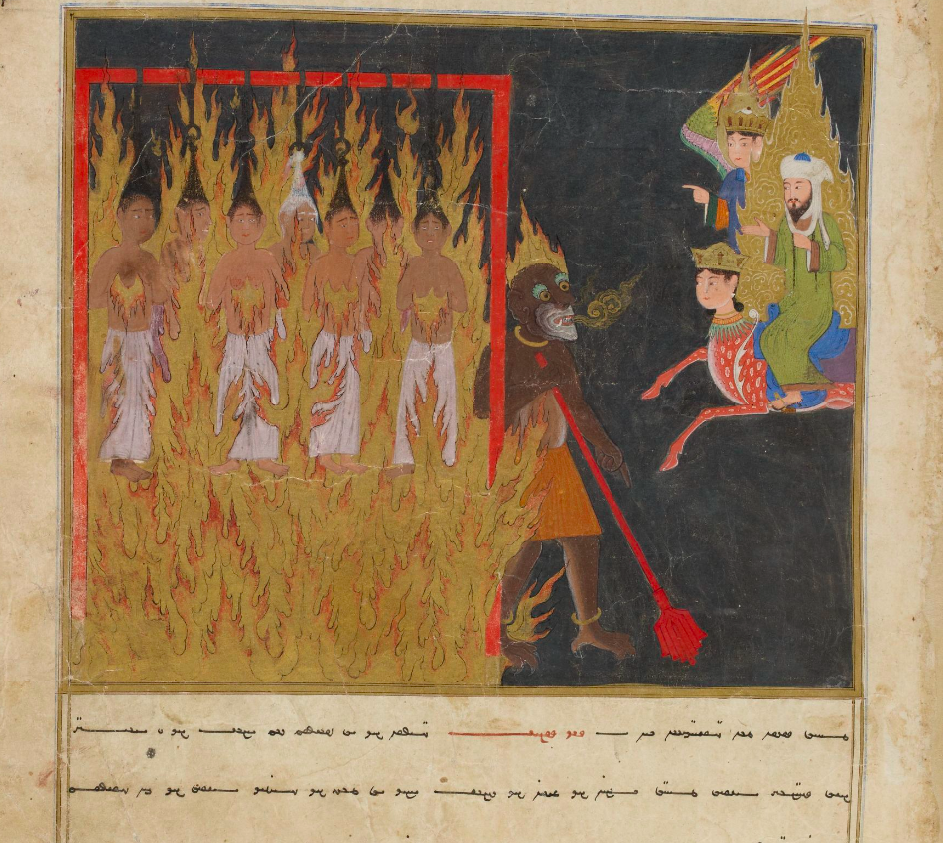

Shah Rukh, Tamerlane’s son who had ordered the manuscript, moved the capital from Samarkand to Herat, where workshops were created that brought together calligraphers and artistscalligraphers and artistsZuhra Rakhimova. The Early Herat Miniature of the First Half of the 15th Century. San`at Magazine, 2010-4. from different regions. This has meant that the illustrations not only reveal continuity with the book heritage of the area, but also feature artistic borrowings from the Chinese and Central Asian Buddhist culture of miniatures. They can be noted in the depictions of the faces, as well as in angels’ hairstyles and poses: the angel of fire and snow, sitting in the lotus position, multi-headed angels, and scenes from hell are worth special attention. This still does not negate the fact that The Book of the Ascension, similar to others of this kind, was a tool used to spread Sunni influenceSunni influenceChristiane Gruber and Frederick Colby, eds., The Prophet’s Ascension: Cross-Cultural Encounters with the Islamic Mi’raj Tales, Bloomington, Ind., 2010.

both within the region and in relations with the Chinese Ming empire.

Out of sixty miniatures, two-thirds depict a flight to Jerusalem on a winged human-headed creature called buraq and the ascent into the heaven, when Muhammad meets other prophets, numerous angels, and appears in front of the throne of Allah. This is followed by only three miniatures that depict the paradise promised to the righteous, where Muhammad sees houris in the gardens, and, finally, a series of miniatures with the torments of hell that await those who would not be allowed into paradise. The complete book can be viewed on the website of the Bibliotèque nationale de France.

Folio 53v: “Then I saw a tree in hell. Its size was five hundred years’ way, its thorns were like spears, and its fruits like demons’ heads. Gabriel said: ‘This is the Zaqqum tree. Its fruit is more bitter than poison. The people of hell eat [of] it. It does not stay in their insides; [rather], it goes right through them. At the base of this tree, I saw a group of people. Angels were tormenting [them by] cutting their tongues. Their tongues grew back again, and they cut [them] again. I asked: ‘Oh Gabriel, who are these people?’ Gabriel [answered]: ‘These are those learned men (culama’) who said to people: ‘do not drink wine, do not fornicate, and do not commit evil and perverse deeds,’ who, not following their own principles, committed themselves these reprehensible and wicked acts.”

Folio 55r: “I saw another group of people. Angels were cutting off their flesh and feeding it to them. ‘Who are these people?,’ I asked. Gabriel answered: ‘These are the people who derided Muslims to their faces and said evil [things] behind their backs without fearing the Day of Resurrection.”

Folio 59r: “I saw another group of women in hell who were hanging by their hair. From their noses emerged of a flurry of fire. I asked: ‘Who are these women?’ Gabriel answered: ‘These are the women who showed their hair to the na-mahram.’ Those people who saw [their hair] coveted them. Evil deeds occurred between them, without them fearing this Day [of Judgment].”

Folio 61r: “I saw another group of people whom angels were tormenting by pouring poison down their throats. It [the poison] was coming out from their posteriors. I asked: ‘What have these people done?’ Gabriel answered: ‘These are the people who consumed the goods of orphans without fearing this Day [of Judgment].”

Folio 63r: “I saw another group of people around whose necks were suspended heavy millstones and whose arms were fettered with chains. Angels were torturing them ruthlessly. I asked: ‘Who are these people?’ Gabriel said: ‘These are the ones who do not pay the tithe on their possessions. With satisfaction in their hearts and not fearing this Day [of Judgment], they were not able to absolve the greediness in their hearts by paying the tithe on their possessions.”

Folio 65r: “I saw another group of people whose tongues were dangling from their mouths. Their heads were like pigs’ heads, and their legs and tails were like [those of] donkeys. I asked: ‘Who are these people?’ Gabriel answered: ‘These are the people who, not fearing the Lord Most High, give false testimony.”

Folio 65r: “I saw some people whom they [the angels] were killing and revivifying, saying: ‘They shed blood without permission.”

Folio 67r: “Then at the gate of hell, I saw some coffins in a place. Inside them snakes and scorpions were emerging and entering again. When I asked Gabriel [about them], he answered: ‘These are people who are proud of heart, evil of nature, and haughty. These snakes and scorpions torment them until Resurrection. They remain in agony.”