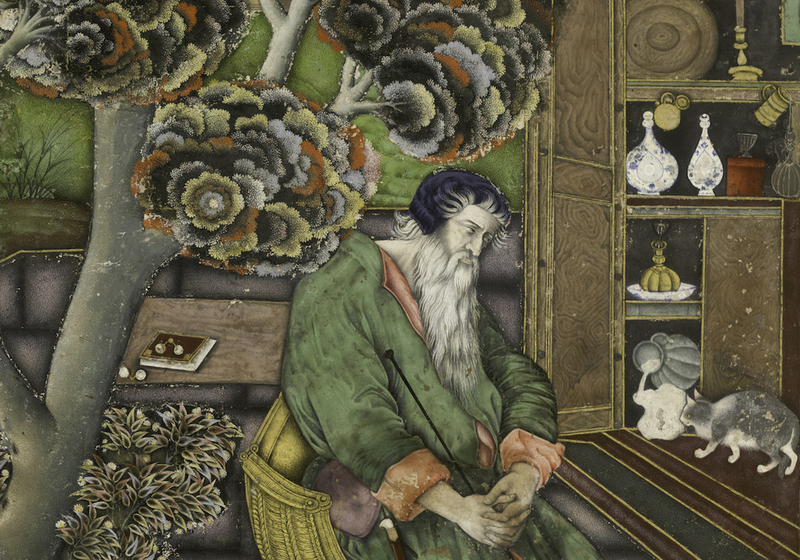

The Shosoin Repository / The Imperial Household Agency

Fragrant agarwood has been revered in Japan for hundreds of years, mainly used for kodo, the traditional incense ceremony that is considered one of the three traditional arts of refinement along the better known chanoyu (the tea ceremony) and ikebana (the art of flower arrangement).

For those unfamiliar, agarwood forms when Aquilaria trees become infected with mold and the tree develops a resin to protect itself. This resin forms in the heartwood of the tree and is what is prized as agarwood or aloeswood, also known as oud wood.

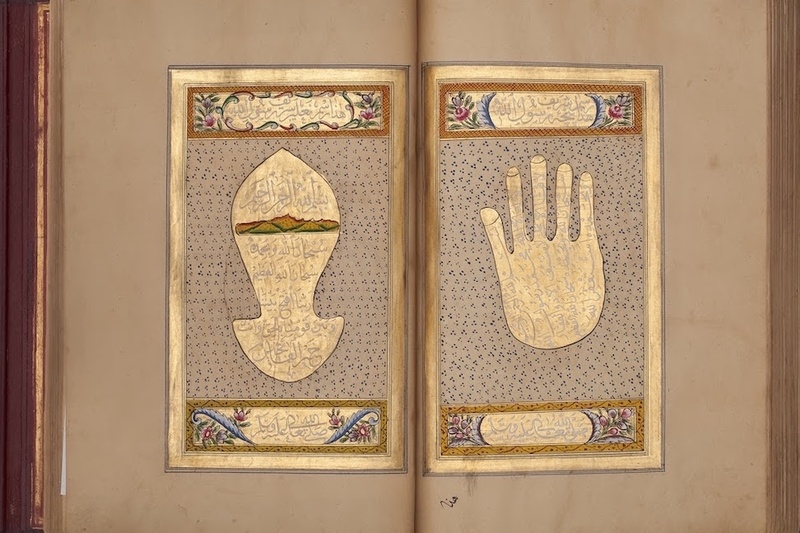

In this rarefied world, there is one piece of agarwood which reigns supreme in reputation and that is Ranjatai. Presented as tribute from China to Emperor Shōmu (AD 724–748), the large log weighs 11.6 kilograms and is 1.56 meters long. The piece was originally named ōjukukō but was renamed RanjataiRanjataiThe name Ranjatai (蘭奢待) is a sort of visual device where the name of Todaiji (東大寺) temple is concealed within the characters. after it was transferred by order of the Empress Kōmyō to the Shōsōin, a treasure repository belonging to Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, once considered one of the powerful Seven Great TemplesSeven Great TemplesNanto Shichi Daiji, the Seven Great Temples of Nanto, are the seven major Buddhist temples constructed in Heijo-kyo (Nara) and its surrounding areas in the Nara period (AD 710–794).

.

The Shōsōin houses a large number of items designated as National Treasures of Japan and after the Meiji Restoration it came under control of the government. Today Ranjatai is considered the property of the Japanese Imperial Family.

Agarwood is not native to Japan nor is the tradition of appreciating rare aromatic woods. As with almost all culture and arts of refinement in East Asia, the original source was China. The appreciation of scent was already a well developed activity among the aristocracy in Tang Dynasty China and it’s likely the practice was brought over to Japan by Buddhist monks or visiting emissaries. What has been lost over the years in China has been preserved, amber-like, almost intact in Japan and the incense ceremony is no exception. Its present iteration is almost an exact facsimile of what the Heian period (AD 794–1185) nobility would have practiced; if an incense connoisseur were to time travel from then to now they would not find anything much amiss.

Perhaps what is most mysterious and ritualistic is that Ranjatai is brought out for exhibition for a short two weeks before the autumn every ten or fifteen years depending on the climate conditions. Indeed, like some sort of saintly relic, it is brought out in hushed tones to a reverent crowd of onlookers who line up to catch a glimpse of what is essentially a piece of extremely old raw wood in a glass case. Obviously they cannot smell it but the mere proximity to such an esteemed object is enough. The last time it was publicly shown was in 2019, within a special exhibition celebrating the enthronement of Emperor Naruhito, eight years after it’s previous display at the Nara National Museum.

The Shosoin Repository / The Imperial Household Agency

Over the years, small pieces were cut from it. In 1465 one small piece was cut as a gift from Emperor Gotsuchimikado to the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. In 1574, another small piece was cut as a gift from the Emperor Oogimachi to the general Oda Nobunaga for his efforts in unifying Japan. Apparently Oda Nobunaga only kept a tiny amount for himself and gave away the rest to various worthies such as the legendary tea-master Sen no Rikyu. In 1877 the Meiji Emperor asked for a piece. Small paper slips attached to the log document these historic cuts.

Typically the most valued variety of agarwood comes from Vietnam and according to Japan’s leading academic on agarwood, Dr. Yoneda of Osaka University, Ranjatai has been identified as either originating from Vietnam or Laos.

Although scent and perfume in the West has feminine associations, the appreciation of scent and the accumulation of rare aromatic woods was almost exclusively a male pursuit in feudal Japan. It was typically the powerful shoguns and daimyos, the warlords who effectively controlled Japan as the Emperor was merely a figurehead until the Meiji Restoration, who would collect pieces of rare woods that they would then name individually. Indeed, Sasaki Takauji, a poet and warrior-aesthete of the Muromachi period (1336–1573) was renowned as the paragon of elegance for hosting extraordinary parties such as a twenty-day seasonal flower viewing at his villa. Some extravagant shoguns would burn entire logs of agarwood during evening parties.

These days it is the Chinese who display such largesse. The Chinese nouveau riche have been buying up large amounts of both new raw materials and old stock held by the historic Japanese incense houses. This has led to a huge price spike to the point that top grade agarwood exceeds the price of gold.