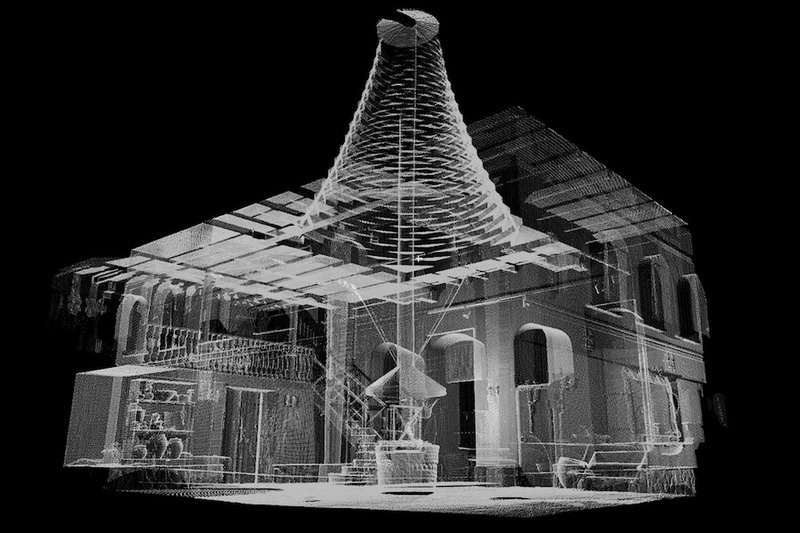

Al Qasimiyah School, Sharjah, UAE. Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023

Images by Ieva Saudargaite (left) and Space Films (right). Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial

The Sharjah Architecture Triennial, a platform for architecture and urbanism, is focused on multi-disciplinary approaches that consider the broader role of architecture, including its relation to social and environmental issues. The curator of its current edition is Tosin Oshinowo, a Lagos-based Nigerian architect, designer, and founder of Oshinowo Studio. In conversation with EastEast, she discusses adaptability, hybridity, unexpected forms of sustainability, and the importance of recognizing spatial and social realities.

For example, in a traditional, pre-industrial African dwelling, the notion of the table and chair were irrelevant because the nature of one’s life and activities did not merit or require it. You would sleep on a mat, you would get up, you would go to the farm. When you came back from the farm, you would sit on a mat underneath a tree, and the only person who was elevated would be a king or a chief of the community. The room was always seen as a place for rest, it was never a place of interaction.

Today, the relationship we have with an internal space is very different. But you can still see the nuances of what it means to be West African or Sub-Saharan African come across in the architecture. And even though this may no longer physically reflect the architectural language of the place, some of these elements are still relevant in terms of function.

Take the reality of self-organizing informal markets that exist in a lot of these cities. These structures that are formalized around the global North in reality still exist here. For example, if you go to an informal market in Lagos, you will notice that all the tomato sellers stay together, as well as all the people selling okras, and all the people selling clothes—because it is in the market’s interest for them all to be located in the same place, and the buyer gets the best price as they go to each person. At informal markets, you never have a fixed price. So they will decide the price based on what you look like. But the thing is, if you go to enough people, you eventually get the best price for the product you’re trying to buy. So it’s in the interest of the market that they stay together, ironically. It is so beautiful when you think about the poetry of this, these self-organizing systems that coexist, that benefit from each other, but actually create an entity that in itself becomes quite sustainable.

You start finding beautiful self-organizing systems that are able to adapt and allow us to coexist in a modern context. It no longer works to think about them in relation to orthodox methodology

Being able to showcase these phenomena at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial means a lot. And what I really enjoyed in the process of curating was the amount of back and forth between myself and the participants. I started to see another set of self-organizing systems occur. It was so interesting to see how people responded after they had received the first prompt. Eventually, we had three strands emerge from the exhibition. The first one is “Renewed Contextual,”,\ which included the participants who were experimenting with materiality, both traditional and modern. These are the practitioners working with upcycling and recycling, introducing gentler versions of modernity. A perfect example of this approach is Al Borde’s project “Raw Threshold” at Al Qasimiyah School. Another participant who did a really beautiful job is Sumaya Dabbagh’s “Earth to Earth.” She works with mud brick walls to create a calming space that just engulfs you.

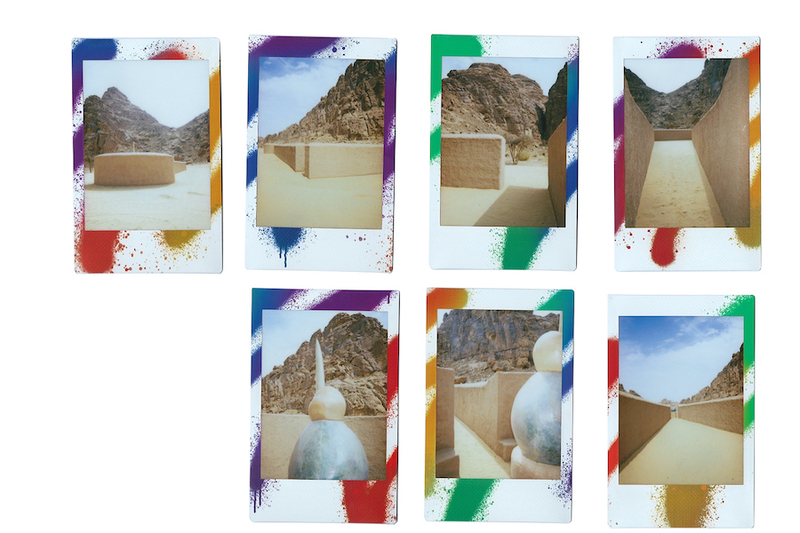

Right column: Cambio by Formafantasma

Al Qasimiyah School, Sharjah, UAE. Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023

Images by Ieva Saudargaite, Danko Stjepanovic and Edmund Sumner. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial

Another strand that emerged from the exhibition is “Extraction Politics”. It includes practitioners dealing with the tensions between modernity, urbanism, and ecology, the reality of what it means to be human and the implication of our consumption on the planet. And we had a loan from FormaFantasma, their project “Cambio,” which was looking at deforestation and the amount of waste that occurs in the pursuit of perfection. And you know, the scale of this is quite disturbing.

Another practitioner who did a brilliant job of showcasing this is BUZIGAHILL from Kampala. In their project “Return to Sender,” they work with second-hand clothes from the fast fashion market. You know, there are droves of used clothes that are sent to Sub-Saharan Africa from North America, from Europe—and a lot of challenges occur with that, particularly because now we are no longer producing cheap clothing with natural fibers. The quality of these clothes is so poor that they just end up in landfills or on beaches.

Al Qasimiyah School, Sharjah, UAE. Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023

Images by Danko Stjepanvoic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial

And the third strand that came about was “Intangible Bodies”. And this has to do with the ephemeral, the spiritual relationship we have as a humanity with our environment. One of the practitioners who did an exemplary job with this, for example, was Sandra Poulson, with her project “Dust the Accidental Gift.” She uses Luanda, where she is from in Angola, as a base reference, looking at the marketplace and the tensions that exist within a city between different economic groups. The areas that were occupied during colonialism were always very hard and clean, while the indigenous populations’ locations were soft ground. You also have a subconscious that comes with this idea of progress. Ultimately, we’ve been sold a notion of progress that is unnatural and detrimental to our ecosystems. Sandra Poulson recreates the marketplace in Luanda with its soft ground condition where one has to navigate between a wet floor and a dry floor, almost dancing as one passes through the city. She also reproduced every single item in the marketplace in papier-mâché. The material smells like slightly wet earth, which is very beautiful.

Al Qasimiyah School, Sharjah, UAE. Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023

Images by Danko Stjepanovic. Courtesy of Sharjah Architecture Triennial

In the process of developing this exhibition, my thoughts and my value system changed because I realized that actually there is no center. Every location, every culture has its value. Before we got to a point of industrialization and globalization, every location in the world had a system that worked. And so many of those have been eroded by a system that came in and imposed the modernity we have all now imbibed. But the reality is that this system is no longer functioning or has significantly detrimental effects. So we need to now rethink what we consider as progress. This really is the point. We have to look back at those traditions and sewas working and now amplify them. We have to scale these because the version we’ve been sold is no longer working.

It is so beautiful when you think about the poetry of this, these self-organizing systems that coexist, that benefit from each other, but actually create an entity that in itself becomes quite sustainable

In the process of putting together this exhibition, I have been incredibly moved. It’s mind boggling how the idea of convenience is creating so much damage. Man has been on earth for thousands of years. All of a sudden, now we all need air conditioning. And we need plastic and every other life convenience: a hundred pairs of shoes per person or three cars. In fact, we do not need all these things.

I do many things: I’ve curated, I’m a practicing architect, I have a furniture company in Lagos: my work is quite hybrid. In the process of putting together the triennial, I became a lot more conscious of the idea of consumption and scale. And as a designer, I very much work off the scale of the one-to-one and the experience of a space: this is quite important to me. It’s also the reason why I’m more drawn to medium-sized projects that are more about the human scale. I also work off an understanding of a cultural context.

In answer to this question, I’m going to give an example. There is a project in Lagos Island, which is the starting point of the city of Lagos: it is where the central business district is and it is near the original residential area of the indigenous people. It’s a very densely populated area and there is a building there, a 75-year-old department store, for which we were asked to do a design proposal. From what my father told me, this department store was the place you went to just before Christmas to get your present. It was a big deal when Lagos was still a colony. It's had many lives: it's been bought by quite a few people, and quite a lot of extensions have been added on. But more importantly, it’s now in the part of the city that no longer has the prestige of affluence it used to. It has a lot of trade, but not the kind of affluent trade it would have been associated with in its heyday. It also has a lot of informal markets surrounding it now, so it is almost impossible to access the building by car; you can only get there on foot.

This department store has been bought by a developer who’s looking to monetize and maximize their assets, so they asked us to do a proposal for a facelift and refurbishment inside. And we suggested they formalize the informal market sellers outside. This is something that nobody would have considered in this environment. The reality is, this building is in a location of Lagos that will always have informal markets outside. If you formalize them, give them a slot and some storage space inside, they can keep their front nice and tidy. This means working with the context. It’s important that, as designers and architects, we work with what we find. We cannot just posit versions of perfection. We have to be consciously looking at the context, the environment, the orientation of the building, and the people you will serve. Our practice has and will continue to be based on these realities.