Bottom: ENDO Kaori’s rooftop farm

All photos courtesy of Aomori Contemporary Art Centre

The Aomori Contemporary Art Center, located in the eponymous city in the very north of the largest Japanese island of Honshu, has been cooperating with the Golubitskoe Art Foundation and the Zarya Center for Contemporary Art in the framework of the program Contact Zones: Far East Exchange. Artist Ulyana Podkorytova was the first ACAC resident from Russia.

Anastasia Marukhina, curator of the Foundation’s research program, spoke with Yukiko Kaneko, the former chief curator of the Aomori, about building international ties and the potential for collaboration between the art scenes of Japan and Russia. With this material, we continue our series of publications in partnership with the Golubitskoe Art Foundation and the Contact Zones project.

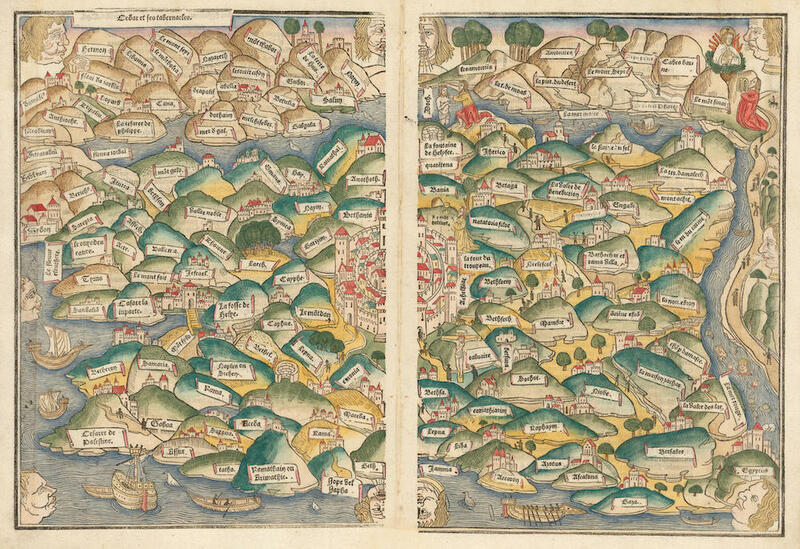

Historically, since the nation was formed, the center of the country was Kyoto or Tokyo and Tohoku was considered undeveloped land from the point of view of those in the center. Due to this understanding of the region, plenty of political issues,including those related to nuclear power plants, have continued to occur in Tohoku. On the other hand, Aomori is known for a large Jomon archaeological site dating back to 16,500~2,500 years ago. It was recommended by UNESCO for world heritage status just this year. Also, there are many traditional crafts such as sugaru nuri (a Japanese lacquer technique), Kogin (embroidery), and Saguri (weaving). Also there are many local cultures and customs—there are different dialects, festivals, and religions that are distinct from other regions.

Furthermore, Aomori has a strong connection with the Hokkaido area because it is very close. Actually, you can see a part of Hokkaido if you go to the very end of the northern part of Aomori on a sunny day. And there are many remains and evidence that people were going back and forth between Aomori and Hokkaido very frequently even before modernization.

In addition, Aomori and Russia, especially Vladivostok, has had connections in terms of trade and cultural exchange after modernization. In conclusion, you can say both that Aomori is the entrance to the Northern world and the end of the main island of Japan. Some may see the sign of the North as an end, but some may think of it as an entrance to the Northern world.

Right: AOKI Noe, Moya –Ⅰ, 2002

All photos courtesy of Aomori Contemporary Art Centre

The ACAC is committed to fully supporting creative pursuits regardless of the artist-in-residence, whether by nomination, open call, or paid residency. Our aim as an institution is to further communicate excellence in contemporary art, construct international networks through these connections, and provide new encounters and learning opportunities between artists, residents, and students in the local community.

The biggest change in ACAC was that the administration changed from Aomori city government to Aomori Public University in 2009. Because of this, ACAC started to focus on higher levels of engagement with the university students although ACAC has involved the students in its project from the beginning.

Second, we changed the condition of the residency in 2020. The past open call residency program asked artists to participate in a group exhibition during the program period. But starting in 20202 we removed this condition for participants. By doing so, it made it easier for dancers, singers, novelists, curators, or researchers who don’t typically present their work in an exhibition format to participate in the program. This change follows the overall situation of the art scene in that a lot of artists collaborate with artists or researchers from other fields.

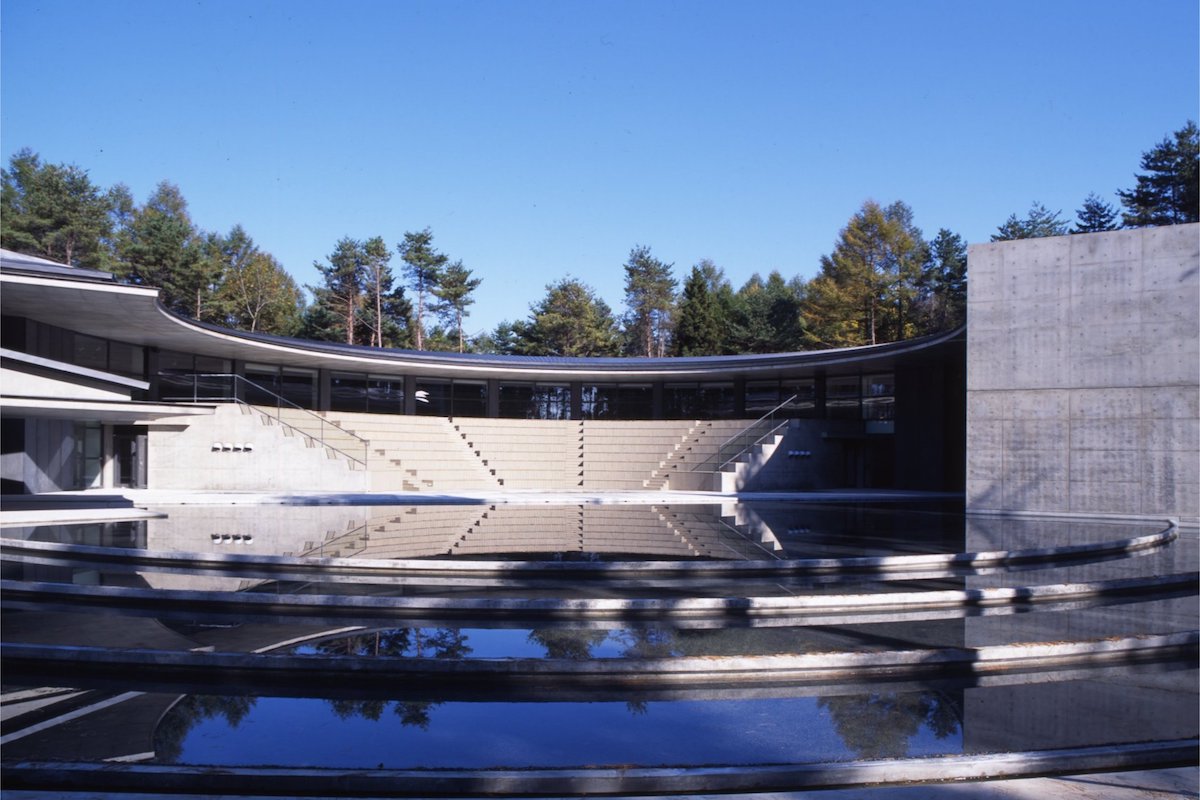

Of course, there are many small changes depending on the conditions, however we could say that ACAC’s core feature is the Artist in Residence program. The reason for that is its building, which is designed for the residency. Our building consists of the Exhibition hall, Creative hall, and Residential hall, and we can say it to lead the path of the artist’s stay and towards them creating new works.

At the time that ACAC was opened, it was the last period of the art museum construction boom by the local Japanese government. So, Aomori city decided to open an alternative art institution that shows new ways of making relationship between art, artists, and local people, and creates a place where art is born from the unique nature, culture, and history of Aomori.

This is why, during the residency period, artists are encouraged to communicate with local people through collaborative production, workshops, performances, school visits, artist talks, etc.

If I could say something:artists make an impact and bring new life to a society. So, if many artists live in Aomori, the community may change toward something interesting.

Of course there are artists living in Aomori, but not so many because there is no art university and there are only a few art related jobs in Aomori. This is why ACAC tries to prompt artists to be involved in the community at residency programs instead of just living in Aomori.

Copyright Ulyana Podkorytova

In addition, artists create alternative ways of utilizing the ACAC building. For example, Nomura Makoto, who participated in the program in 2012, started farming on the roof of a residential hall. It is covered by soil in order to fulfill the concept of “buried architecture” by Anda Tadao, and many wild plants thrive there naturally. In his residency, Nomura cultivated a part of it and made a vegetable field as his artwork. After that, the students of Aomori Public University have been looking after it for the last five years. And last year, in 2020, the artist Endo Kaori created her own field for her production there. She grew cotton and indigo there. This is one of the most interesting stories in which the artists showed new ways of utilizing ACAC’s architecture.

This is why it is meaningful to build a relationship and develop a cultural exchange between ACAC and ZARYA CCA / Golubitskoe Art Foundation that is based on this history.

On the other hand, the area where the Golubitskoe Art Foundation is located is on the western side of Russia and next to the eastern side of Europe. ACAC expects to find some of the cultural diversity of Russia through geological differences and to start a dialogue about it. Also ACAC expects to build good relationships with ZARYA CCA and Golubitskoe Art Foundation through the program. The relationship between each institution will create a new cultural sphere that serves as a network.

Copyright Ulyana Podkorytova

In addition, the biggest reason is that there has been strong economical, historical, and political connections within the Far East region because we are neighbors. Owing to this, each country has experienced a lot of conflict. However, we can build good relationships with other countries because we are neighbors. Art can be one of the tools for it. Art can illustrate a lot of aspects that people don’t recognize in our history, economy, and politics. This is why ACAC believes that interdisciplinary research gives us new perspectives and helps to deepen our understanding of the Far East region, as neighbors who create a future together.

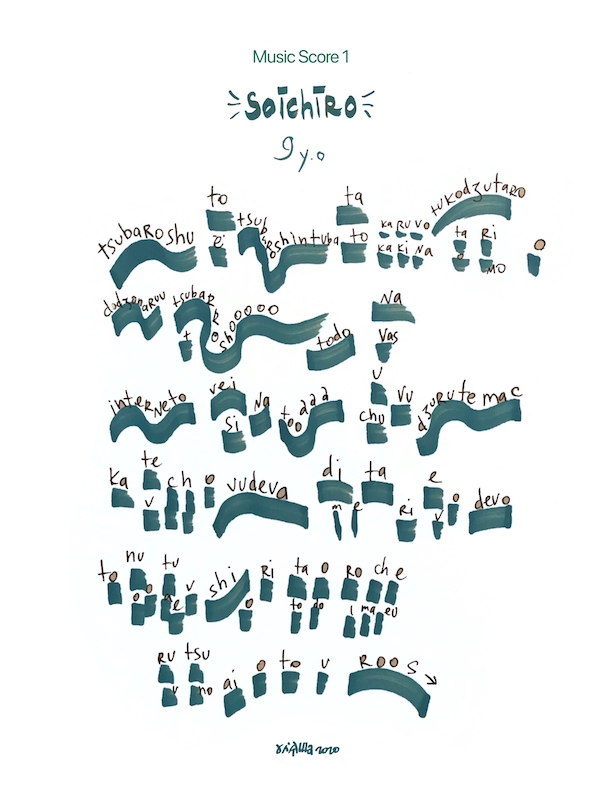

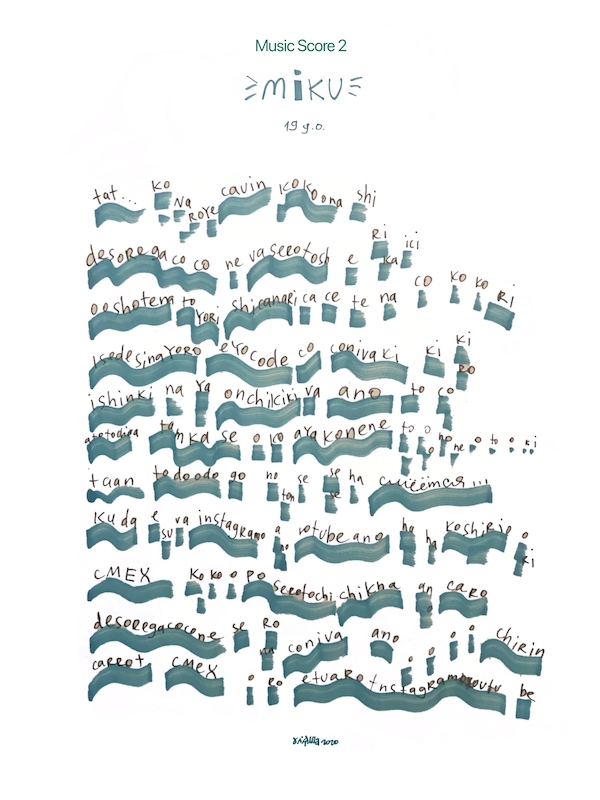

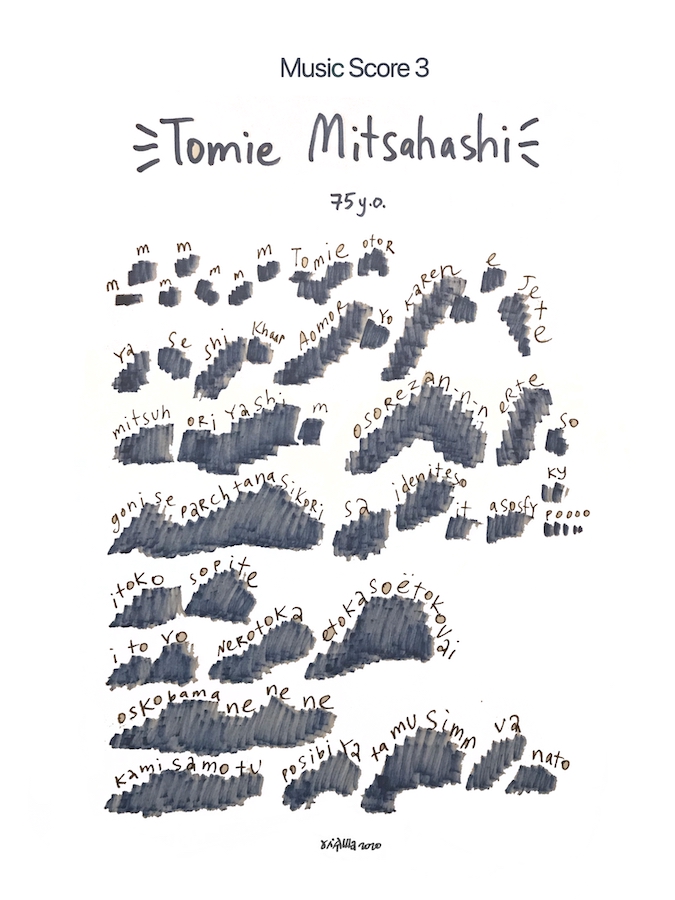

In 2020, she interviewed three Aomori residents, whose ages were seventy five, nineteen, and nine via the internet. Her questions ranged from basics like name and age, to urban legends, Aomori rumors, local gods or hero—the inspiration for the motifs of the local Nebuta festival, to things often seen here and there across the internet. The interview concluded with the participants singing their favorite songs for the artist. Moreover, Uliyana held an artist talk and presented a voice performance as an online public event after her interview.

ACAC was not able to invite her but asked her to participate remotely in 2020. We hope to invite her in 2021 once COVID-19 is over. According to this condition, she proceeded with her project with the hybrid of online and offline modes in which she interacted with ACAC and Aomori over a long term period. Despite the fact that she participated in our program during the latter half of her work and she didn’t have enough time, she made powerful progress in her research. It is the first time we have had this format. This is why these are challenging and interesting tasks for ACAC. Her way to proceed with the project shows us how we can adjust our way of programing in this period of the “New Normal.”

Copyright Ulyana Podkorytova

In 2020, we tried “online” residencies with foreign artists. ACAC was able to conduct it thanks to the cooperation, generosity, and ideas of each of the artists. Not only Uliyana’s practice, but also other artists tried a lot of ways to reach the local community. For example, Amélie Bouvier (France) and Sara Ouhaddou (France/Morocco) created a mechanism for gathering visitor’s comments about their solo exhibition and did so in a way that allows for offline exchanges. They will use the comments that they gathered in their new artwork. On the other hand, Alicja Czyczel (Poland) and local participants sent many texts, photos, and short movies to each other for about three months. It was like exchanging their diaries. Her practice showed that sending the messages over a period of time brings their friendship closer.

Based on these experiences in 2020, we are sure that artists’ practices are opening doors and pushing the limitations of being“online” and are going beyond our imagination, though of course there are still many disadvantages to an online residency. ACAC is continuing our “Remote Residency” through our open call program in 2021, and we are looking forward to creating new ideas with artists. We can use both online and offline efficiently even after COVID-19. So we consider this an opportunity to develop new ways of running a residency.