Jun Kitazawa is a Tokyo-born artist who currently lives in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. In his projects, he works with various communities to create spaces that are “neither private, nor public,” to introduce a sense of lightness into what are at times critical circumstances, and to explore the possibilities of everyday life and different ways of home-making. Jun told EastEast about his initiatives in Japan and Indonesia as well as what he’s been learning from his homelands.

All images courtesy Jun Kitazawa

I’m from Japan, but I’m living in Indonesia now. I worked in Japan for around ten years, with community residents all over the state, both in the countryside and in cities—because my work always implies collaboration with other people. But later, some of the long-term projects with local residents just came to their logical end. For example, the project with people living in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster area—around 50-60 km from the nuclear station. The area was damaged by the tsunami more than by the nuclear accident—entire villages disappeared beneath the waves. The residents I worked with in Japan lived in the sea-side village that was destroyed by the tsunami. Four years later, they got their new houses—and just like myself, they have changed. For four years they had lived in temporary housing, but after their situation had changed, in 2015, my projects were finished too. I was seeking change as an artist too.

When I moved to Jakarta, I was so shocked—I had real culture shock. I was born in Tokyo, and the reason why I became an artist is connected to my life in Tokyo. When I was a highschool student, communication with other people would always confuse me. In my teens, when I was conversing with others, I would always think: why am I talking about this? Why do I know what I know? Expressing myself, I’m always feeling conscious about what I’m conveying. And this became my artistic thinking. But I’m still wondering where the way I express myself is coming from. Why can I express this or that, why can I use the language that I’m communicating with, what is the identity of my expression? This was an important question for me. Becoming an artist was my answer. In my daily life, I’ve always been creating. When my parents sent me to school, I was playing a student—we are always playing someone in society.

And this constructed daily life is so systemic in Tokyo. You know, if you need to go somewhere, you never have to wait for more than ten minutes at the station. In Tokyo, everyone works very hard, and we cannot create our rules by ourselves, our daily lives are already being constructed by someone else. So I wanted to let my art projects out into this constructed society, to create an alternative daily life. With projects like Living Room and Sun Self Hotel, I used the names of ordinary places to create fictional spaces. But ten years later, I was done creating the alternative daily life as a long-term project in Fukushima, as well as with Living Room and Sun Self Hotel. We need to always keep changing, so I wanted to join a daily life that I didn’t know. That’s why I moved to Indonesia.

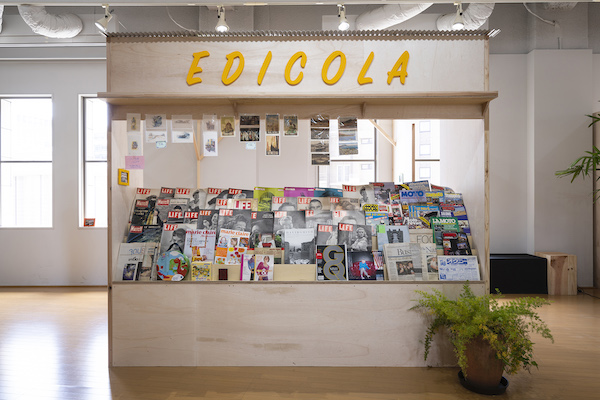

Jun Kitazawa started the first Living Room by having the interior of an abandoned clothing store painted white. Used carpets and furniture were collected from households in the neighbourhood, furnishing the newly emerged “living room,” where people could spend time at their will, chatting or reading books. From 2010 to 2016, the project was carried out in Kitamoto Danchi (Kitamoto, Saitama Prefecture), Ryogoku Honmachi (Tokushima, Tokushima Prefecture), Takanosu (Kitaakita-city, Akita Prefecture), Sakaemachi-Ichiba (Naha-city, Okinawa prefecture), Izumicho Kaikan (Mito city, Ibaraki prefecture), Kujiragaoka arcade (Hitachiota city, Ibaraki prefecture), and in Sankhu (Kathmandu, Nepal).

Living Room is one of my representative projects. It’s a long-term undertaking addressing the present-day social situation in Japan. My projects don’t just come from my own initiative—I always join the community that I’ve suggested my project to. Living Room had to do with the transformation of space: I changed the vacant store into a public space. Many shops are closing, because in the recent twenty or thirty years a great number of malls appeared in suburban areas—most people stopped going to the stores near their own houses. The population of Japan is decreasing too…

My projects often have to do with the idea of home. Home has many meanings. A house can be only one of them, but home is also about a feeling, not just a place. Many people who join my projects do not have a home. One of the examples are the people who lost their homes after the tsunami. And in the cities too, many people participating in the Living Room project didn’t have a "home" of their own either. In the area where I created Living Room, one of the locals had a mental disability and didn’t have a feeling of home in the community. Some people cannot feel at home anywhere, but they join my projects to experience it. This is similar in all of my initiatives.

In Jakarta, society is not so rigidly constructed as in Japan. There was no particular reason why I chose Indonesia—it was all about the first impression. I didn’t know what to expect further, but looking back, I can explain what I felt at the time. There was no pre-constructed daily life—from my own point of view, not from the point of view of the people of Jakarta, of course. But I saw how people living in Jakarta were creating their daily lives for themselves: they would build houses out of materials found in the streets… It might be called a slum, but it’s artwork as well. I understood why I was creating my art projects in Japan: I wanted to intervene with pre-constructed patterns, but there wasn’t anything like that in Indonesia. After that, having encountered a fundamentally different daily life, I think I upgraded myself, got a new concept of a dual locality. In Tokyo, the reason why I wanted to make my projects was an essential question for me, but they were also created by the society itself. Artists themselves are being created by the society. But when I’m asked about the dual locality, the dual common sense, I can depart from the local rules, both Japanese rules and Indonesian rules. Now I’m looking for the similarities and differences between the two communities. For two or three years now I’ve been working with Indonesians and other immigrants living in Japan. There are so many different people from other countries living in Tokyo, but locals cannot see them, because the Japanese society is very closed and introverted.

Neighbour’s Land is the project I conducted in 2018, after I moved to Indonesia. It took place at YCC, in Yokohama. Yokohama was one of the first places in Japan that opened to other countries. The American Navy first entered Japan from the harbor in Yokohama in 1853. So, Yokohama has a long history of connecting with other countries, both in a good sense and in a bad sense. As a result, there are many people from around the world living there: from America, the Philippines, Indonesia, as well as those from European countries. I offered them to join my project and create a fictional land, a fictional country in the exhibition space.

In my view, Indonesian society offers so many opportunities, there are already so many gathering places. Many people cannot rely on the government: the ones who live in slums, or people with disabilities. But the atmosphere of the neighbourhoods can help them. What I was doing in Japan as an art project already exists in the communities of Indonesia. In a sense, it’s a much more inclusive society. If the society in Indonesia doesn’t fail, they will preserve their intrinsic discipline and their gathering places. The reason why I want to keep doing my projects in Indonesia is because many of their participants aren’t aware of what they already have. I think it is important to notice the beauty there, and I still have the motivation to show it.

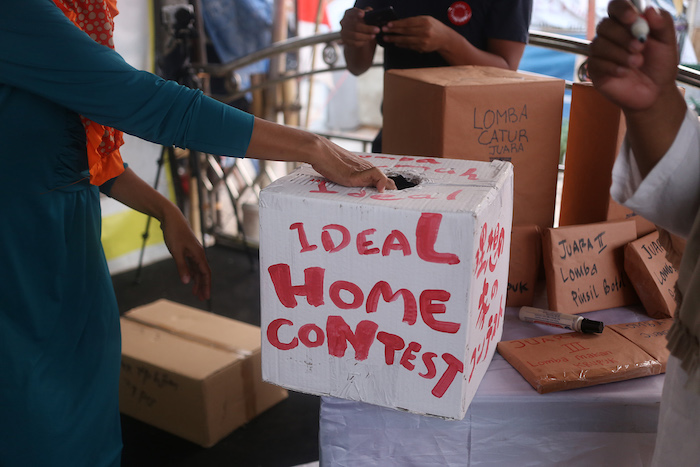

One of my main projects in Jakarta is also connected to the concept of home: it is called Ideal Home Contest. Because of the urban development in Jakarta, there are numerous areas that are like small villages within the city area. In Indonesian, they are called kampung—it’s a typical phenomenon in Southeast Asian cities. Kampungs become targets for destruction during government-driven urban development. So, I worked with the former inhabitants of one of the kampungs that had been demolished. In 2017, I met the residents of Kampung Akuarium—I was invited there by my friends. When Indonesia was occupied by the Netherlands, Dutch companies constructed lots of buildings in North Jakarta, one of which would later give the name to the kampung. Later, Japan occupied Indonesia, and after Indonesia got its independence in 1945 many people from the countryside started actively moving to Jakarta and settling in the available areas.

In April 2016, the Kampung Akuarium people were asked to leave the village so that the government could build apartment houses there and turn it into a tourist area. Eleven days later Kampung Akuarium was destroyed entirely, all of the houses, everything. When I came to Kampung Akuarium in March 2017, nearly one year after the demolition, many of the people were still living there, in tents or in improvised constructions. The landscape shocked me. The people of Kampung Akuarium reconstructed their settlements on their own. They brought electric cables, got access to water… But in the media, it was presented in a controversial way—some of them said it wasn’t the government, but the residents who were guilty, because it was regarded as illegal to settle in this area. This has been one of the most disputed areas in Jakarta at that time—there have been numerous publications, including one in National Geographic, and many NGO’s have been helping the residents.

Seeing this, I started asking myself: what is a home? The inhabitants of Kampung Akuarium had to move, they had to create their dwellings themselves. There are all kinds of people living in Jakarta, and many of them can not imagine what has been happening in this area. But those who are being forced to move have to constantly think of what a home means to them, what they want to get back is not just the land, but the soul as well, the feeling, the connection; not only the visible, but also the invisible. The question I got for the people living in Kampung Akuarium, in a situation that other residents of Jakarta could hardly imagine, was “What is a home? What is an ideal home?” Humans in general are always moving, they have never stopped moving around. The common belief in Japan these days is that Japanese culture was formed in a vacuum, but that’s not true. There have always been numerous connections—because humans are always moving. Throughout our long history, we’ve all been constantly searching for an ideal home.

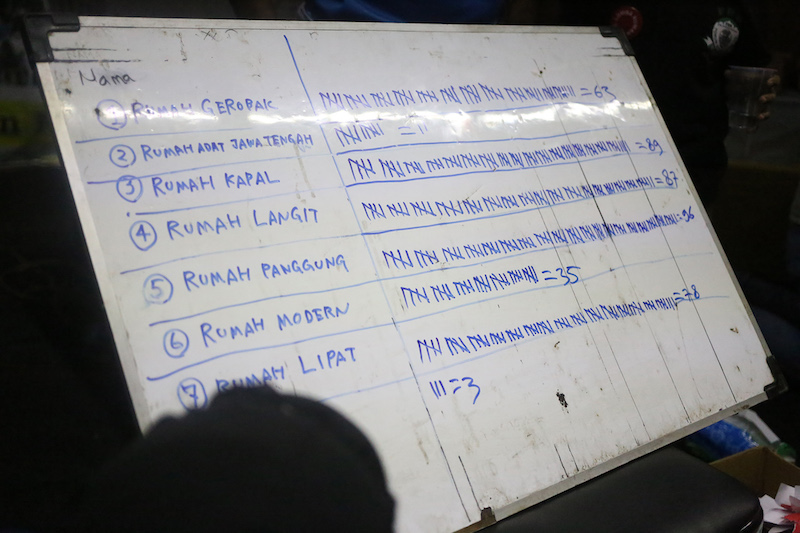

My project in Kampung Akuarium was aimed at thinking about what makes an ideal home. Many of the kampung residents celebrate the Indonesian Independence Day by organizing various contests—like eating contests where people compete to see who can eat their food faster. There are all kinds of contests being held on that day. And Jakarta is frequently facing political conflict, but the people there always love having fun. I wanted to connect my questioning of the political situation with the Independence Day celebrations, so I organized a new contest: although everything that it was about was already there. This way, it could be fun, and it could be an art project as well. The contest for the residents of Kampung Akuarium was about creating an ideal home. I was going there daily for about three weeks, and we would be discussing everything. The residents put together seven teams and each of them created a model of an imaginary house. There was a House in the Skies, a House with a Stage, a Folding House… The House in the Skies was a dreamy idea coming from the children of Kampung Akuarium. They said, “If we have a house in the sky, no one can come and destroy it.”