The exhibition Qatar Between Land and Sea. Through Arts and Heritage has opened at the Russian Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg and will be available until August 22nd. It was organized by the Cultural Creative Agency in partnership with the National Museum of Qatar, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, and the Sheikh Faisal bin Qassim Al Thani Museum. We present comments from major art historians and curators who worked on the show: they discuss the exhibited artifacts, some key phenomena of Qatari culture, and how the leading museums of the Gulf preserve local traditions.

Director of Curatorial Affairs

Deputy Director for Research and Collections

Curator of Archaeology and Early History at the National Museum of Qatar

Dedicated to bringing the history of Qatar to life, the National Museum of Qatar strives to actively voice the nation’s heritage and culture, and to demonstrate the extensive network of ties with other nations from all around the world.

Designed as a chronological and immersive space, the Museum tells the story of Qatar and its people, exploring Qatar’s rich heritage and history from the earliest times to the present day. The story unfolds in three chapters, over eleven galleries. The first chapter focuses on the geology, archaeology, and natural environment of Qatar, where visitors can experience images, artifacts, and models—from the formation of the peninsula and first human settlements, to the amazingly diverse natural environment that we know today. The second chapter explores the history of life in Qatar, looking at how people lived on the land and on the coast for centuries before the discovery of oil. In these galleries, visitors can listen to the stories of the people, see the objects they crafted and traded, and listen to their poetry and songs. The final chapter of the Museum tells the story of how Qatar became the nation that we know today. From the 1500s to the present, the galleries explore the challenges and triumphs that have shaped the modern state and also look beyond—to Qatar’s vision for the future.

In an effort to celebrate cultural relations between Russia and Qatar, the National Museum is displaying a selection of objects at the Russian Museum of Ethnography.

Director of Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museums

Exhibited artworks reveal the common thread of cultures that connect communities from as far apart as North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. They introduce Islam’s visual culture and its far-reaching traditions, manifesting the beauty of memorabilia that lies in the stories of the museum’s founder, Sheikh Faisal bin Qassim Al Thani. The objects represent but a selection of Sheikh Faisal bin Qassim Al Thani’s modern version of a Cabinet of Curiosities, the historic and eclectic room of marvels from the Renaissance that amazed connoisseurs and collectors throughout time.

On display, objects span over a hundred years, ranging in size: from an intricately decorated glass lamp to engraved ivory boxes, or precious gemstones and jewellery never exhibited before outside of Qatar. Although it could be thought that artifacts from Qatar are an intrinsic part of its Islamic heritage, art from the Gulf region embraces not only the art created in the service of Islam.

However, Sheikh Faisal bin Qassim Al Thani’s complex of Museums is much more than a series of gallery spaces. We want to inspire people to learn through our collections, exhibitions, and public programs, both locally and internationally.

Founder of FBQ Museums

My love for history and collecting heritage artifacts began when I was young. My father, may his soul rest in peace, was a passionate traveller and lover of culture. He was keen to share his enthusiasm by taking me with him on his travels to visit museums and ancient cities everywhere. I soon realized that my mission was to find objects that express my cultural heritage—artifacts from Qatar and the Gulf region.

As the size of my collection increased, people became more interested and started asking about it. To start with, the collection was located in my private majlis and available only to those who wanted to see it. Nevertheless, although I was glad to show these treasures to anyone who showed interest, I wondered what I could do about all the people who had no opportunity to contact me personally. Therefore,

I decided to display my collection in a private museum, which grew and grew over time as if self-propelled. The existing artifacts are very diverse and not limited to a specific civilization or culture, so every person who visits the museum finds something that they can relate to.

While some artifacts are highly valued in terms of appraisal, others do not necessarily have a significant material value. But in terms of historical and cultural relevance for the Arab world, they are all priceless. They speak to you; they tell stories about Islamic civilization, our past, and our ancestors' culture. My aim is that the museum will serve as a beacon for the next generation of young people to follow the same approach by taking care of our history, our culture, and encourage them to collect artifacts.

Curator at Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum in Qatar

Heritage is the spirit of the past, present, and future in relation to humanity. Qatar enjoys abundant cultural wealth and a remarkable patrimony. The state of Qatar shows a great interest in different areas of cultural life, for instance, by the establishment of libraries, museums, theaters, and art centers. Besides this, many traditional popular professions are at the core of the government’s plan to be preserved and fostered, such as the sea, hunting, and desert-related activities.

Folkloric Qatari culture has a unique character as it has been present in this blessed land throughout all Arab-Islamic history. People have celebrated their beliefs with pride since Qatar’s earliest ancestors sacrificed their blood to their land. The celebration of cultural patrimony informs the West and the rest of the world about Qatar’s distinct traditions and customs as witnessed by historical places that highlight Qatari heritage, such as the shapes of ancient houses and markets, the Fort of ZubarahFort of ZubarahIn Arabic, Zubarah is a low hill, a pile of stones. The Az-Zubarah Fort is one of the main attractions in Qatar., and other distinctive places across the country.

In this direction, culture and heritage represent the roots of Qatar’s identity, for which the country stands out compared with other Islamic nations. Qatar’s confidence in civilization through culture has led to successful advancements across many fields of human knowledge. Qatar has never stopped transmitting its history through a renovated form of storytelling (hakawati) in order to keep narrating untold stories of people and their lands.

Art historian

But no: the argument that museums are new to Qatar can hardly really explain much. The country's current cultural landscape refutes it: hyper-modern, it combines Western architectural and museological traditions with local imagery. To name but a few examples: the rarest Arab manuscripts are stored inside an alien-seeming angular structure, the Qatar National Library designed by Rem Koolhaas; its repository’s stone corridors, reminiscent of archaeological excavations, are situated in the middle of the building, at the bottom of an amphitheatre of bookshelves. By the old jetty for dhows (traditional fishing sailboats), an artificial peninsula was created for the Museum of Islamic Art, a quintessential example of Muslim architecture translated by the architect Ieoh Ming Pei into the straightforward language of minimalism.The futuristic building of the National Museum of Qatar, designed by Jean Nouvel, borrows the form of a desert rose, whose petals cover the restored old museum building, now itself an exhibit. The inherited material evidence of Qatari history—from palaeontological finds to the pipes carrying the first oil—is integrated into a high-tech immersive space made up of videos, sounds, and smells, simulating local nature, leading the visitor from the beginning of time into the present and attempting to construct a new national identity.

Against this background, the Sheikh Faisal Museum deliberately stands out. Its collection is too vast to fit the mission of cultural heritage preservation; rather, it seems to invite comparisons with sixteenth-century cabinets of curiosities, in which stuffed animals, herbaria, minerals, works of art, and ancient artifacts coexisted as equals. In this respect, it makes sense to see the Sheikh Faisal Museum as an allegorical “Majlis of Things,” providing representation for objects that so far speak for themselves. The traditional majlis is neither a house nor a museum— it is a space where the private and the public intersect, where absolute hospitality reigns, and where the decoration includes the best carpets and objects dear to the owner. The potentially open model of the collection, inviting all things and beings living and non-living, distinguishes it from the boundaries of museums with their “maniacal conservation” of the past, which paradoxically only formalizes the final breakthe final breakBruno Latour and Catherine Porter. We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press, 1993. with the past by putting things in showcases. Museums simultaneously recognise the impact of the objects on display and neutralise the possibility of their political participationpolitical participationAngels Without Wings: A Conversation Between Bruno Latourand Anselm Franke // Animism: Volume 1 / Ed.by A. Franke. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010. P. 86–87

.

Perhaps the answer again lies in the double meaning of the word “majlis.” Circling back to its definition as a space of hospitality, we also learn this: when an Arab tent welcomes guests, this traditionally involves a performance by a hakawati—a storyteller (the word is ultimately derived from the Lebanese verb haki: to tell, to talk). The principle of a hakawati narrative is to pause halfway through a story and move on to another one—within which yet another may lurk, often told by a new narrator, and so on, seemingly to infinity.

Art history PhD

The Qatari way of life is depicted in the following thematic collections: pearl diving equipment, falconry utensils, weapons and military tools, rugs and carpets, camel and horse riding tack, religious manuscripts, clothes and jewellery, musical instruments, coffee ceremony articles, and selected household items.

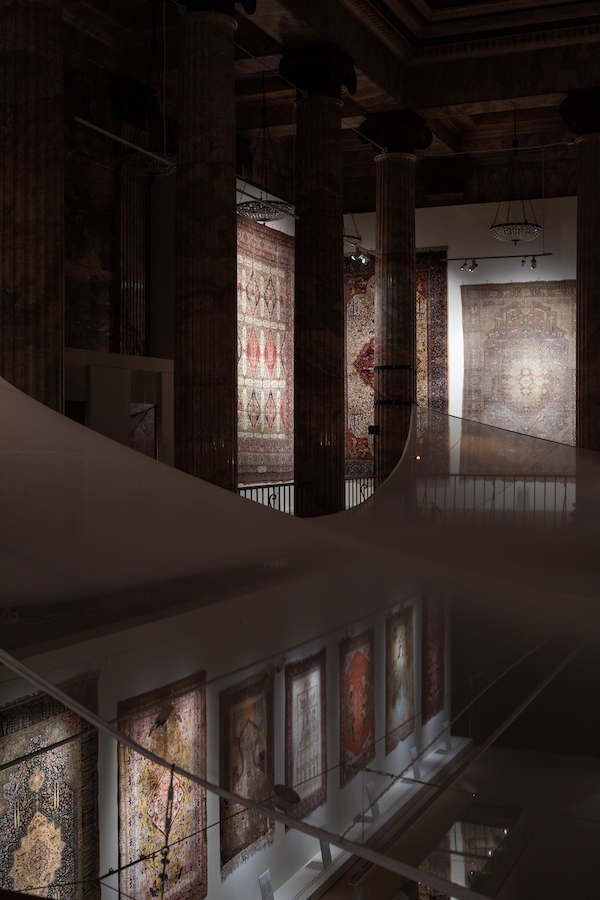

Oriental rugs are the collective name for the highly decorative carpets made from sheep, camel, and goat wool, cotton, silk, and linen in various Asian and Middle East countries.The technique has not changed much over the centuries, though the portable looms of nomads were simpler than the stationary ones in workshops and manufactories.The rugs displayed here were made in the centers of artistic weaving in Turkey, Iran, and India from the eighteenth to the early twentieth century. An early example of the craft is a prayer rug from eighteenth-century Turkey. Its central motif is a mihrab (prayer niche), which is surrounded by Quranic scriptures and facing qibla, the direction towards the Kaaba in Mecca.

This type of prayer rugs is made to hang on the majlis walls, pointing towards the Kaaba in Mecca (Saudi Arabia). Caring gestures such as this one would help guests orient themselves at the prayer time if left alone in the house. Nowadays, to find Mecca's direction, prayer apps and digital geolocators are available extensively on modern phones.

Right: Rug. Kashan, Iran, early 20th century

Medallions, animals, and a Farsi poem feature in this Seneh-knotted Iranian rug.

FBQ 7395, FBQ 7401 / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum

Prayer rugs serve for individual prayers, keeping worshippers clean during the ritual: by physically separating them from the floor or ground, the rug symbolically separates them from the outside world. The most classic Oriental rug is the Persian carpet (from what is now Iran). The Iranian technique is characterized by the finest workmanship and sometimes includes the introduction of gold or silver threads. A woollen carpet manufactured in Kashan at the start of the twentieth century exhibits the typical medallion composition with floral and animal motifs. Between them, mirrored images of wild animals appear, among which we can recognise lions, leopards, cheetahs, tigers, fallow deer, and goats. The images on such rugs resemble manuscript illuminations—which is not accidental, as the models were often commissioned from miniaturists.

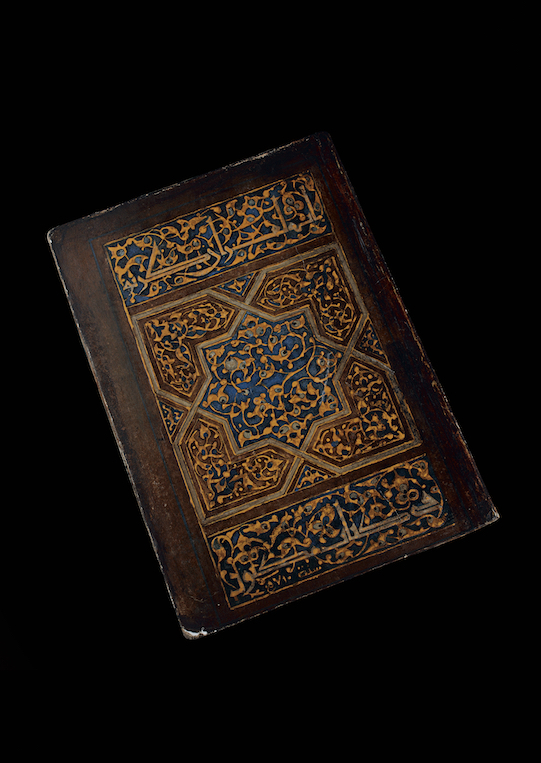

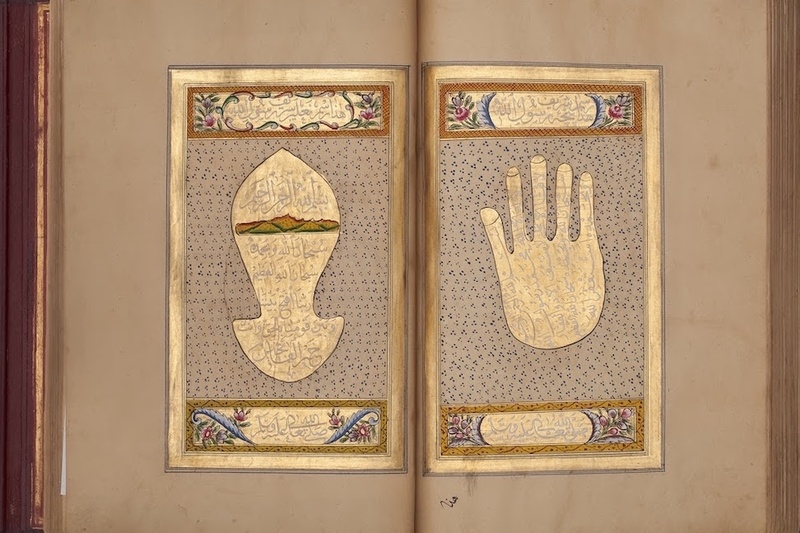

In every culture that has writing, written words have a special value—spiritual, but also material. Even after the invention of printing, books did not immediately become widely available. Sacred writings were and remain the most commonly produced printed matter on the planet; they also prevail among the surviving ancient books. It is not surprising, then, that this section of the exhibition is fully dedicated to the Holy Quran. A particularly striking example is the seventeenth-century Quran from Bukhara. Its leather cover is decorated with a polygonal mesh pattern reminiscent of glazed tiles. The religious prohibition on representing humans promoted the development of geometrical and vegetative decor in Muslim countries.

The heavy and translucent fabric was worn by women in the desert to protect their skin from the sun.

Right: Face Cover (Battoulah Al-Rayasi) Qatar, 20th century.

This battoulah al-rayasi (nujum) is trimmed with gold embellishments. A battoulah al-rayasi (nujum) would be worn by a wealthy woman, such as the wife of a pearl merchant or boat captain, in public spaces, including the majlis if men were present. Fine examples like this would be worn for religious or wedding celebrations.

FBQ. 8959., QNM.2012.259.1. / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum, National Museum of Qatar

The clothing of Qatar’s inhabitants has generally retained its national character, though, in recent times, it has undergone some changes under the influence of European fashion. The basic garment of the male population is the robe called kandura. Under it, Arabs wear an undershirt and loose loincloths forming a kind of trouser. Most men’s clothing is made of natural white fabrics (linen, cotton): they reflect light and attract less heat while also denoting dignity and nobility. The bisht, a cloak most often made of camel’s hair, can be black, coffee-colored, or beige and sometimes features embroidery on the edges. Unlike the kandura, the bisht is not meant for daily wear but only for important receptions and major celebrations such as weddings.

An integral part of the Qatari women’s wardrobe is the abaya: a floor-length unbelted long-sleeved dress, most often simply black, but sometimes sumptuously decorated. Outside, women traditionally hide their faces under a burka, which includes a headscarf covering the head and face except for the eyes; in seldom cases, a metal construction called the battoulah is used, covering part of the forehead, nose, and lips. A burqa is not compulsory in present-day Qatar; women may wear any long dress with a modest neckline and sleeves at least up to the elbows.

It is in jewellery that the Oriental tendency towards opulence finds its most eloquent expression. In Qatar, fashioning jewellery from precious metals and gems is a traditional family craft.

Right: Necklace (Murryah Um Tablah) designed to protect the wearer from evils. Qatar, 20th century

FBQ. 2042.1–4, QNM.2012.597 / Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani Museum, National Museum of Qatar