In her book Invention Of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (1997), Nigerian scholar Oyeronke Oyewumi describes how the imposition of Western gender categories influenced the social relations in Yoruba society. Feminist researcher Victoria Kravtsova discusses the importance of this work for the development and expansion of decolonial thinking.

In the 1990s, a “decolonial turn” took place in the social sciences, which was first described in Russian by Madina Tlostanova. This “turn” presupposes a rethinking of modernitymodernityModernity is the cumulative designation of the historical era characterized by industrialization, urbanization, secularization, the development of state institutions, and civil society. The decolonial “option” asserts that modernity always has an underside—coloniality. This term denotes a system that arose as a result of colonialism, where "Western" societies are positioned at a higher level of development and non-Western societies are forced to “catch up.” from the perspective of its “dark side,” coloniality. Decolonial scholars have criticized postcolonial studies—an earlier form of criticism of colonialism—for their “Western” epistemological foundations and suggested that in the future such criticism should be based on local practices and knowledge. Particularly interesting for us are the works that analyze how the modern understanding of gender was formed under the influence of modernity/coloniality. Maria Lugones described how not only race but also gender was invented during colonization. She and other decolonial and indigenous scholars demonstrate that within the hierarchy created during colonization, white women experience one form of discrimination and non-white women are discriminated against twice: as women and as non-whites. Discussions about the point at which “non-Western” societies became patriarchal, as well as descriptions of communities where the understandings of gender differ from “Western” ones, occupy an important place in the literature on gender and decolonization. An example is Invention Of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (1997), in which Nigerian scholar Oyeronke Oyewumi describes an epistemological shift caused by the imposition of Western gender categories on the social relations in YorubaYorubaYoruba (Yoruba: Ọmọ Yorùbá) is a group of peoples inhabiting sub-Saharan West Africa (Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Ghana).

communities.

Oyewumi points to a paradigmatic difference between “Western” and “African” feminism. According to her, this book is not about the “women’s” question, since such an understanding is an export product of “somatocentric,” that is, body-focused, Western thinking (1997, XV). Oyewumi's book challenges the basic tenets of feminist literature of the time, where gender was understood as the fundamental organizing principle of any society; where there is a universal category “woman,” which is invariably subordinate to the universal “man.” Oyewumi criticizes the approach of Western feminists, calling it “sisterarchy”: they reproduce the same hierarchical imperialism of Western thinking that they seek to destroy. Together with black feminists and feminists of color, she insists that women should no longer be perceived as a homogeneous group, since not all stories of discrimination are the same.

In Western societies, only a woman possessed a body, while a man was a “walking mind.” In colonized societies, everyone was reduced to the body

According to Oyewumi, although “Western” gender theories argue that biological sex and gender are not the same, in fact, even such subversive ideas as the queer theory of Judith Butler only reinforce the inseparability of sex and gender. She describes the basis of “Western” science as “body-reasoning” or “bio-logic”: the body is constructed in it as simultaneously biological and social. Oyewumi believes that “Western” culture is so concentrated on the body because the visual component of it is very strong: the main sense organ here is vision, which invites one to distinguish and thereby produce the Other. For her, the priority of vision is associated with the Cartesian dualism of body and mind, where the body is a prison from which you need to break out. In this paradigm, the Other for the Western subject is the one for whom the body is more important, who is governed by affect and instinct and not the mind. In Western societies, only a woman possessed a body, while a man was a “walking mind.” In colonized societies, everyone was reduced to the body. Oyewumi believes that even such critical directions of Western thought like Marxism are also “somatocentric.” Although sociological categories such as “working class” are social, they are still rooted in biology: for example, when someone mentions “corporate leaders,” we imagine only the bodies of white men.

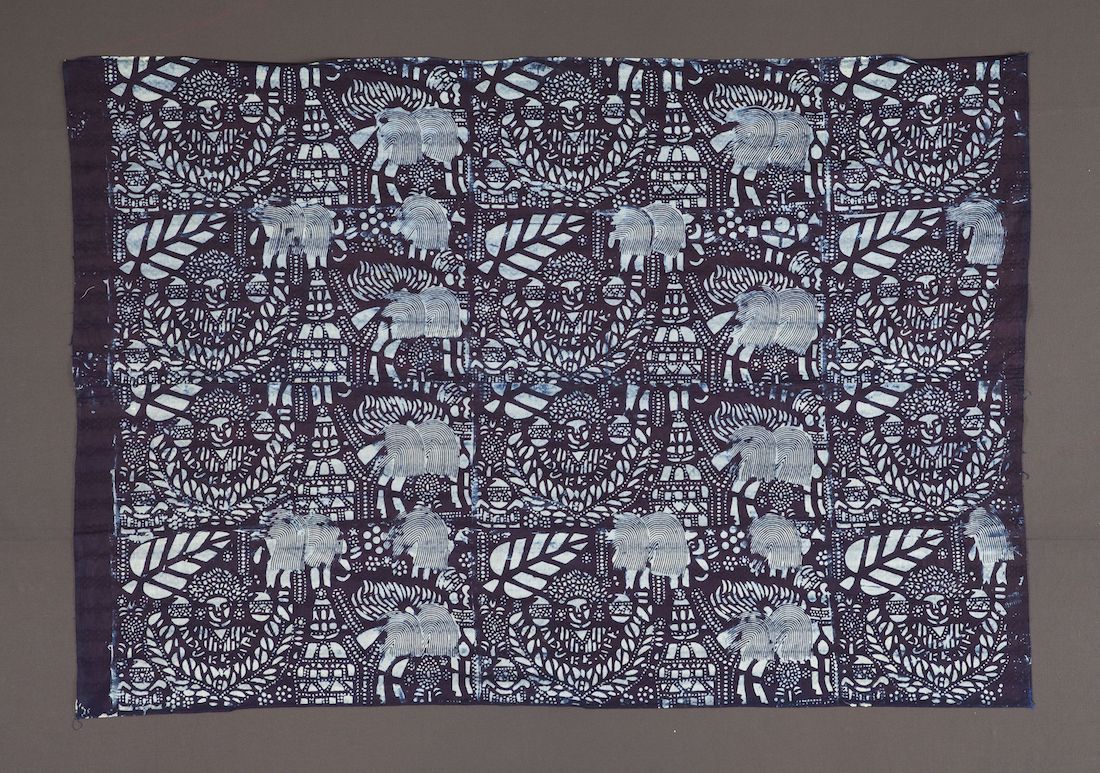

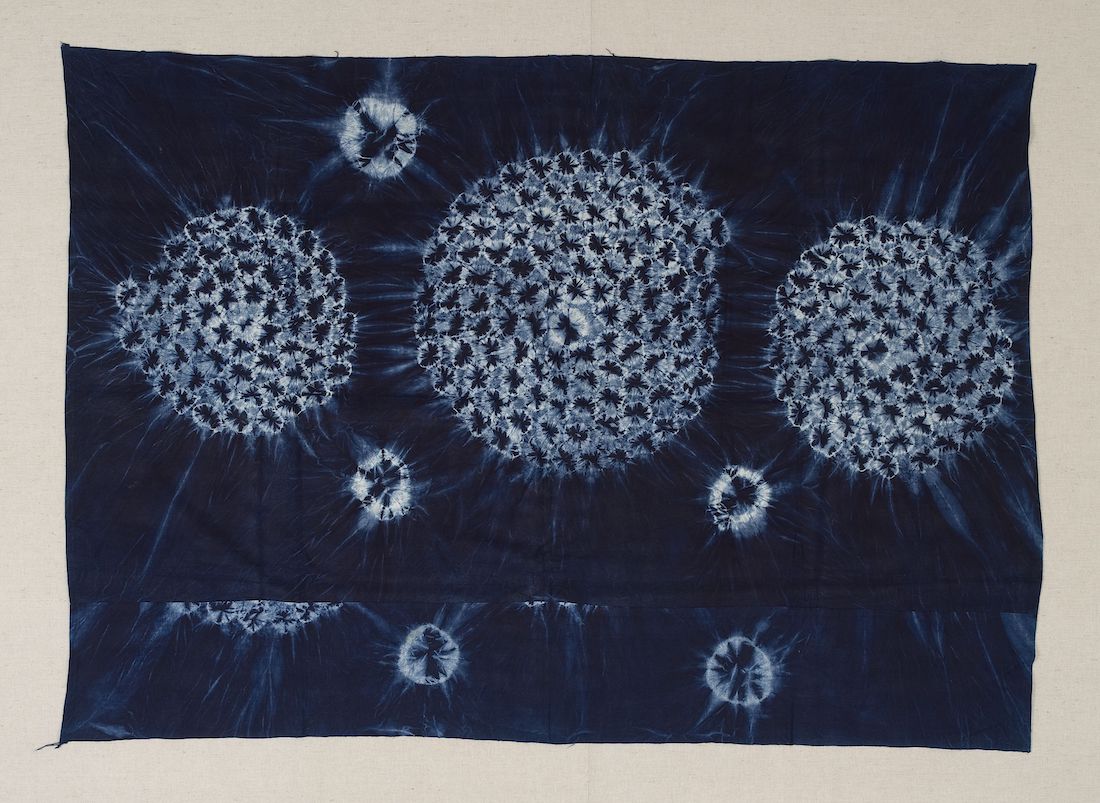

Adire cotton capes made by patterned dyeing of fabric with indigo pigment. This cape is traditional clothing for both men and women: it is wrapped around the body and the ends are tied together. You may learn more about this technology here.

2008/59/23, 2008/59/22, 2008/59/21 / Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

Oyewumi emphasizes that she does not mean that people from African countries should not get acquainted with Western theory—on the contrary, it is necessary in order to adequately respond to the challenges of global capitalism. However, it is also important to write one’s own story. Whereas in Western science the presence of other gender orders in the world is described in the logic of their “discovery” by the West, Oyewumi writes about Yoruba from the Yoruba perspective. She notes that while in Western culture the word “worldview” is used, for Yoruba culture the term “world-sense” (1997, 3) is more appropriate—a perspective on the world where vision is superseded by other senses, the main of which is hearing. In this perception of the world, Oyewumi explains, gender categories cease to play an essential role. Oyewumi is not trying to present the Yoruba society as free from hierarchies—they were there, but were constructed not between people of different genders, but depending on their age. Identity in Yoruba society was fluid: it was constantly shifting under the influence of who the person was interacting with at a given time. However, Western sciences, rooted in biology, describe this society in familiar terms. African science, institutionalized after colonization, also pays little attention to local specificity. “For many African intellectuals, Africa remains only an idea” (1997, 25). They study Western theories most of the time, and African knowledge is supposed to be simply absorbed “through the mother’s breast milk” (1997, 26).

Anafemales could be at the same time rulers, mothers, children, priests, and occupy any position in social structures, depending on their situational status

Since in pre-colonial Yoruba society there was no social hierarchy based on anatomical differences, Oyewumi uses the words “sex” and “gender” as synonyms and introduces new terms for her research: “anatomical female” and “anatomical male” or “anafemale” and “anamale.” In Yoruba society, she writes, social relationships were influenced by social factors and anatomy did not determine who could rule and who could trade in the market. Neither family nor other social structures depended on anatomy. Anafemales could be at the same time rulers, mothers, children, priests, and occupy any position in social structures, depending on their situational status. According to Oyewumi, words in the Yoruba language translated as “man” and “woman” have nothing to do with the gender binary: they are not in the same inter-relation as “wo-man” and “man,” there is no hierarchy between them. The woman in the West had no power and no publicity, which was not true for the Yoruba obinrin. This word, like okunrin, is nothing more than a designation for reproductive anatomy. As an example, Oyewumi names prostrations in front of the elders—obinrin do them on their knees, while okunrin lie down completely. This happens not due to a different status in society, but because of the possible pregnancy of the obinrin. Even though the reference to anatomy is present here, these categories are not dimorphic, that is, they do not imply a strict separation between the two genders predetermined by biology.

In the Yoruba language, names and pronouns have no gender. For example, “child” is a neutral word that the Yoruba still prefer over “boy” and “girl.” Reproduction and growing up are the two pillars of human differentiation for the Yoruba. Oyewumi gives the example of marriage, which in “Western” feminism is usually understood as the “enslavement” of a woman. In Yoruba culture, the anatomical woman did not conclude an alliance with one anonomic man, but entered a family. Then, not only her sexual partner became her oko (a term that is usually translated as “husband”), but also all his relatives with any anatomy. The hierarchy within one’s own kin was lined up according to the time of birth and the hierarchy within the kin of the “husband”—according to the time that they entered into the family. Both structures were hierarchical, but an anafemale had different status and opportunities in the family where she was born and in the one she entered. Not noticing this, Western anthropologists described Yoruba gender relations as contradictory. For instance, women could do the same things as men, but had to kneel in front of them. In describing this, they did not take into account the fact that anafemales kneeled before all “elders” in the family they entered—including other anafemales: there was no single leader in the Yoruba families, and power, although not in equal shares, was distributed between everyone.

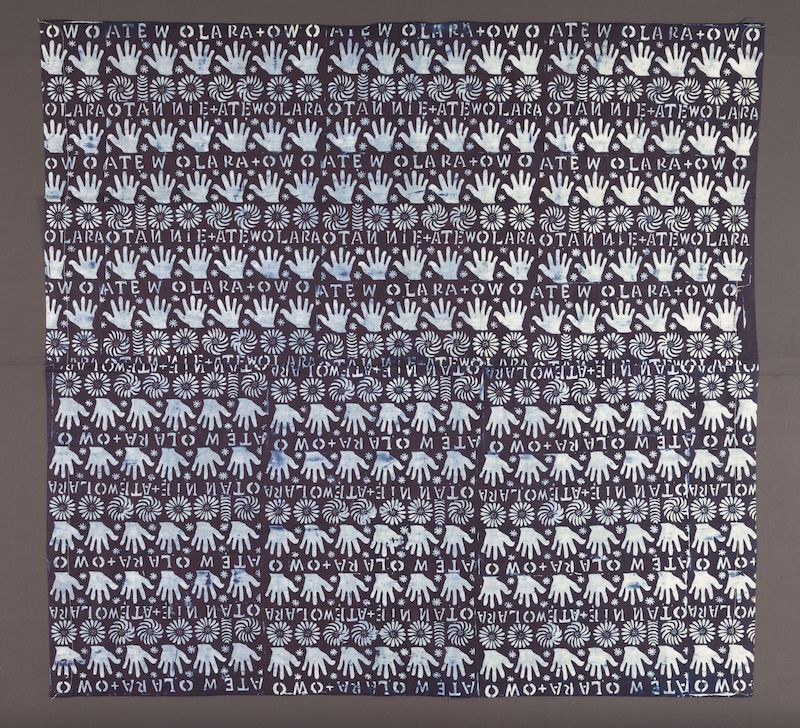

2008/59/18 / Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

Another example of the patriarchal nature of Yoruba marriage that anthropologists usually cite is the existence of a ransom for a woman to enter a new family. Criticizing it, the investigators did not take into account that the ransom provided only the new family of the anafemale the right to her sexuality and offspring. The husband's family had no right to her personality, work, and property. The main purpose of marriage was children, after the birth of which the mother retained financial independence and both she and the father could be polygamous. The anatomical female also did not have to do household chores and cooking, she could trade or work in the field. Anafemales mothers cooked, but men did too, and often the food was simply bought. The professional activities of both anatomical men and anatomical women were also related to the kin—an anafemale from a family of hunters could more easily become a hunter than an anamale from a family of merchants. Yoruba did not have a gendered division of labor. Oyewumi argues with the quantitative arguments of Western science that there were fewer women in the prestigious Yoruba professions. These studies do not take into account, for example, which child a particular woman or a particular man was, or whether they were children of the first or the second wife. Gender categories were understood as the most important, although in reality they could not matter much less.

The history of Africa was oral until it began to be recorded by the colonialists. Therefore, written historical sources, as a rule, translate the perception of local events through the prism of Western categories. In the chapter “Finding a King in Every Man,” Oyewumi writes about how Western assumptions of how roles are usually distributed in society led to the transfer of power among the Yoruba to be interpreted as taking place along the male lineage: a woman could be a regent, but not a ruler. She refutes this assumption, bringing up historical examples of anafemale rulers. Today, finding one is almost impossible, although Oyewumi met such a ruler in one of the villages during her research. Western scholars also made other mistakes: for example, they described the ancestral songs performed by the Yoruba as produced only by women, although both men and women took equal part in their creation. Also, trade has been misinterpreted as an area of female activity. Oyewumi also problematizes homosexuality attributed to the Yoruba culture, as in the absence of binary gender categories it is impossible to understand it here in the same way as it is done in the West. Oyewumi writes that polygamy and sex before marriage were normal for Yoruba. However, sexuality could also be limited—for example, anamales often abstained from sex until they saved up a ransom to marry. Therefore, assumptions about either excessive conservatism or the shameless “savagery” of the local gender order are both incorrect.

Colonization did not eliminate, but brought gender discrimination into Yoruba society. Women in Africa have been colonized twice—as Africans and as women

As Oyewumi writes, gender as a category was not relevant to the analysis of the Yoruba societies prior to colonization. After colonization, however, it was impossible to study gender orders in Africa without considering the influence of the West. Some researchers describe the transformation processes of gender relations in Yoruba society as positive, because women, for example, received property. Here again, the fact is not taken into account that women were not only part of the “husband's” family, but also remained included in the kinship structures of their own families and owned property regardless of marriage. Colonization did not eliminate, but brought gender discrimination into Yoruba society. Women in Africa have been colonized twice—as Africans and as women. Christianization and the imposition of the European economic system led to their exclusion from the public sphere. The autocratic colonial system did not imply that anafemales could be rulers. Certain gender relations were imposed: for example, the church forbade intercourse outside of marriage. Within the educational system established by the colonialists, boys were more readily accepted into school, and special educational institutions were opened for them. Education for women became available much later. Gender was introduced into the local religion: Orises (gods) who did not have any gender became predominantly men. In addition, customary law was introduced, where women had a subordinate status. Gender roles in Yoruba society have also changed due to the transformation of the economic system. An institution of land tenure was introduced: previously belonging to the entire kin, land was then assigned to men. Men were again involved in building and maintaining new infrastructure, such as railways. Traditional economic spheres, such as trade, were also undergoing transformations, during which women were forced into the household and became dependent on men. The “invention” of African women by the colonialists meant that they became invisible.

2008/59/19 / Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

Oyewumi problematizes the fact that the Yoruba language is usually used by researchers only to work in the “field,” and its own significance is not recognized. Even the Yoruba themselves continue to write about Yoruba in English, reinforcing the universal status of modern/colonial categories. For Oyewumi, the existence of binarism in the English language meant that it would be reflected in the way it was used to describe Yoruba society. Therefore, the Yoruba language is non-binary, and English is the opposite. Throughout the book, we repeatedly see examples of how gender-neutral Yoruba words were endowed with masculine gender—“son” instead of “child,” “man” instead of “person,” “king” instead of “ruler.” The Yoruba also borrowed binary English words such as “madam” and “sir.” The more people in Africa used European languages containing binary categories, the more they internalized them. This is noticeable, in particular, in the literature of local writers.

Black and postcolonial feminists have shown that “woman” is not a universal category, and it is important to pay attention to other logics of discrimination

The “patriarchalization” of Yoruba culture that occurred during colonization is supported today by the politicies of international organizations: the UN is an agent of the Western patriarchal system and women's and feminist organizations export Western understanding of gender throughout the world. The book points out to those involved in feminist activism or research that it is always necessary to be attentive to local specifics. When examining Yoruba society, for example, one should ask different questions—not “What is the gendered division of labor in this society?”, but “How is difference and inequality constructed here?”. In Oyewumi's book, little space is given to describing how Yoruba society functions nowadays. However, she mentions that the Yoruba resisted the establishment of a heteropatriarchal order, for example, by founding their own independent churches where women had equal rights with men. Other practices are found in Yoruba and other African societies that undermined the enforced gender order. You can read about them, for example, in the anthology of African gender studies edited by Oyewumi.

Oyewumi has made a major contribution to the development of transnational feminist thought. Black and postcolonial feminists have shown that “woman” is not a universal category, and it is important to pay attention to other logics of discrimination. Decolonial scholars like Oyewumi are expanding our understanding of what gender is and how its formation relates to colonialism. In the countries of the former USSR, a similar approach is used, for example, by Alima Bissenova from Kazakhstan. This perspective has also been criticized—for example, for being overly “fascinated” with pre-colonial societies, and for the fact that these ideas can easily be adopted by right-wing nationalist movements. Nevertheless, demonstrating the possibility of a different distribution of gender roles in society is of key importance for the development and expansion of feminist and decolonial thinking.