In August 2020, cofounders of the ethnographic label Ored Recordings Bulat Khalilov and Timur Kodzokov accompanied by DJ and curator Nikita Rasskazov went to the Adyghe village of Ulyap in Russia’s North Caucasus to research and record local traditions of criminal chanson and Soviet banquet songs. After the expedition they wrote an article for EastEast, dedicated to the multi-layered identity of region inhabitants, permeable genre boundaries and the way local musical thought can turn any elements of culture into a part of its heritage.

From a musical perspective, the region has everything: family ensembles, solo performers, and traditional music projects. On previous occasions, we travelled to Adygea for the region’s epic storytelling and melodies to accompany healing rituals. These songs and tunes are no longer performed as everyday practices, but the works themselves are still alive in the memory of local musicians and in archival recordings.

However, this time, we chose a less obvious, more unusual topic: a Circassian variation on the Russian criminal chanson and Soviet banquet songs. The format of the expedition allowed us not only to capture one of the less-studied layers of the region’s traditional culture, but to theorize about the borders of tradition, authenticity, and understanding of what constitutes “native” and “non-native,” since the Circassian chanson is a blend of ritualism and kitsch, local and supranational.

Any conversation about traditional Circassian culture has to start with the story of the Caucasian War, which ended in 1864 with Russia’s colonization of the Northwest Caucasus and the subsequent deportation of the Circassians to the Ottoman Empire (and thence to Syria, Jordan, and other countries). And we should not forget that Soviet authorities split the Circassian ethnos into three republics and three different (from an administrative point of view) peoples: the Kabardians of Kabardino-Balkaria, the Circassians, or Cherkess, of Karachay-Cherkessia, and the Adygeans of Adygea (the Black Sea Shapsugs are also often considered part of this group).

Striving for unification and proclaiming unity on the one hand and defending sub-ethnic identity and cultural specificity on the other create, while not exactly contradictions, a diversity of views on culture

Most Adyghe see this longstanding separation—first with the help of the war machine and then the administrative system—as the biggest problem. For this reason, Circassian activists today are particularly focused on unifying the various tribes and diasporas.

Dedicated social media communities and channels publish texts, videos, and even memes with a unifying message: one nation, one language, one name—Circassians. In fact, there are two names: while to an outside audience they are Circassian, they describe themselves as Adyghe. Many activists deny later definitions and identities (like, for example, the broad Soviet definition of “Adyghe” instead of indicating a specific Adyghe subgroup). They are calling for an end to the practice of splitting them into sub-ethnoses, to choose one language instead of dialects and proclaim themselves as one united Circassian nation. In the opinion of some activists, although this would eliminate certain dialects, it would return to the Circassians the unity that was lost or taken away during the Soviet era.

Striving for unification and proclaiming unity on the one hand and defending subethnic identity and cultural specificity on the other create, while not exactly contradictions, a diversity of views on culture and self-representation, even within a specific background. To an outsider, the majority presents a common Circassian identity, while among themselves, they defend the right of sub-ethnic groups to self-determination, uncritical disputes, and even a competitive spirit.

This multi-layering also strongly affects the situation in music since art (whether traditional or served up as traditional) is one of the chief instruments of self-representation. And the culture within the Adyghe community—when people play music not for concertgoers, not for audiences on YouTube, or visiting TV crews—encourages a regional sound. Yet in Russia, “serious” and “professional” art coverage often ignores local subgenres in favor of standard mainstream pop, which is based on the ideas of those who led the typical regional ensembles of the Soviet period.

ULYAP—THE BIRTHPLACE OF CIRCASSIAN CHANSON

Ulyap is a small mountain village, or aul, in Adygea. According to official sources, it was founded in 1861 during the Caucasian War. Since its very foundation, Ulyap has been home to Circassians of different tribes: Kabardians, Abzakhs, Besleney, and others.

Researchers, journalists, and the Adyghe themselves today speak of Ulyap as an oasis of Circassian music. During our preparations for the expedition, we were informed that there are many accordionists in the village. “There you can go into any house—you’ll record somebody!” they told us.

This is not far from the truth since music, and the accordion in particular, has always been part of the unofficial Ulyap brand. This genre, so revered by the locals, is lyrically characterized by a love of courage and a romantic view of the criminal world. “In Ulyap, we sing well, drink well, and beat well!”

Criminal and traditional music converged in a remarkable way in one local variety of chanson (in the way the term is understood in the post-Soviet world): during a banquet, traditional and ritual melodies would smoothly segue into prison hits like “Golubi letyat nad nashei zonoi” (“Doves Fly Over Our Prison Camp”), and folk songs about Nukh Aberegov would become chastushki (two or four-line rhyming couplets) about the criminal world and the rejection of communism. Adyghe chansonniers added a Circassian backing vocal to these songs, inspired by the region’s epic sagas, and began to beat the rhythm not on the Caucasian dhol drums or drum machines typical of pop cabaret, but on traditional percussion instruments.

The liminal nature of Ulyap chanson is expressed not only in the blurring of the boundaries between Circassian musical tradition, prison folklore, and Soviet hits, but also in the context in which the genre exists.

THE HOME OF ADYGHE CHANSON

Until recent times, banquets and weddings were the main ceremonies where this music was played. Both rites are important events that both formed and preserved the musical culture of the Circassians. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, there was a custom in the Caucasus—and to this day among the Circassians of Turkey—called mekhsymafa. A kind of cross between a men’s song club, a collective musical performance, and a prayer, mekhsymafa was a banquet involving music and the consumption of an alcoholic drink called mekhsyma. Today’s feasts may not be so obviously sacral, but in Ulyap, it is nonetheless usually during a banquet that music is played.

One of the main audio documents of Ulyap chanson, which we used as a reference point and which inspired us before our trip, is an anonymous cassette with recordings by a duo called “Murat and Ilyas.” In just over an hour, they appear to deliver almost the entire repertoire of Ulyap criminal chanson. There is no way of confirming this officially, but it seems likely that the cassette was also recorded during a banquet: the clinking of glasses and plates, heated exclamations, and other noises are excellent confirmation of this.

The dzheguako chansonnier

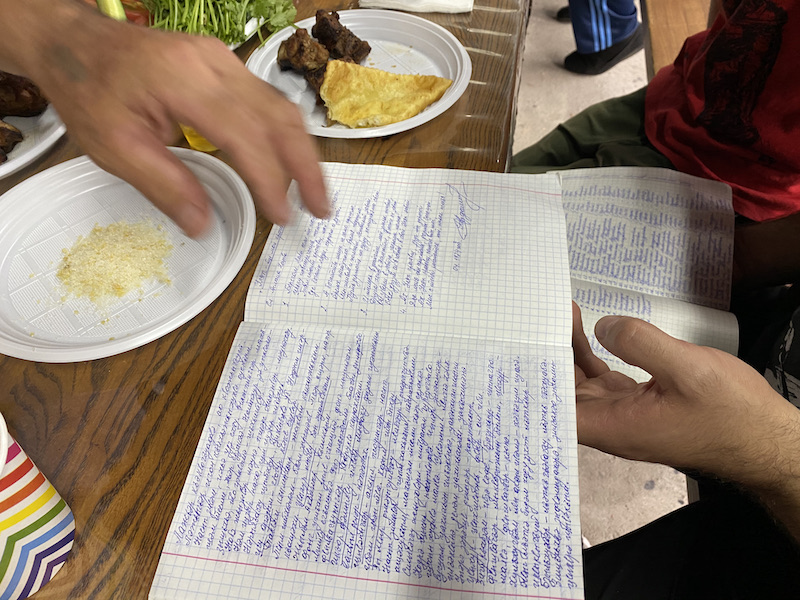

Yura Nagoyev, who became our chief guide to Ulyap chanson, is a musician, improviser, and connoisseur of local traditions. As Nagoyev strongly believes that a banquet is the best occasion to sing these songs, he suggested doing the recording not in a studio but during a spontaneous dinner with friends. Therefore, the recording couldn’t be any more authentic: Nagoyev talked about music not as an ethnographer but as a lover of convivial conversation.

He fell in love with music in the early 1980s, when working as a long-distance truck driver. To begin with, he just listened to Adyghe virtuoso accordion players at weddings and then taught himself during long journeys. Today Nagoyev is one of the most prominent accordion players and wedding musicians in Adygea. In the past, a wedding could last for several days, and a musician was always one of the key elements of the celebration. In fact, Nagoyev recalls how at weddings, he would have to play for eight hours in a row, and while dance and wedding tunes were always in demand, the repertoire of rough banquet songs also went down extremely well since it was almost always appropriate for the occasion.

During the recording session, Nagoyev talked about his life as a long-distance truck driver, how he had played music at weddings and read poems and jokes in the Adyghe language, Russian, and Ukrainian. He easily overcame the borders between different genres and formats. For him, it was important while on record to convey everything that was precious both for him personally and for Adyghe culture in general.

The Ored Recordings expedition prompted Nagoyev to draw a parallel: in 1911, the British company Gramophone made a recording of Magomet Khagaudzh, one of the most prominent accordion players and dzheguako (minstrels) of the last century. “This way, with the help of the British, we’ve been able to hear how Khagaudzh played. His music has been preserved, and now it will never disappear. This is important,” stressed Nagoyev.

Another interesting parallel to be drawn here is that Yura Nagoyev could himself be described as a modern dzheguako. The storytellers and bards of the past preserved the epic sagas, sang about heroes and traitors, performed rituals, and performed songs about topical issues. And while Yura only preserves strictly local musical traditions, improvises with established texts and melodies and does not create new ones, the similarity with dzheguako performers in his work and character is unmistakable.

Although the boundaries of “folk music” and “other music” are blurred, musical thought and the aesthetics of tradition are capable of turning any elements of musical culture into a part of their heritage

For the second day of recording, Yura gathered most of the old-school Ulyap accordionists and traditional percussion instrumentalists in order to introduce us to different performative variants of local traditions. It was all pretty official: even the head of the district administration came to greet the musicians and ethnographers. Yet this didn’t prevent anyone from creating the atmosphere of a boisterous feast once again.

On the one hand, the Ulyap musicians said that the music, accordion, and simple songs were their greatest patrimony and would never disappear, but on the other, they lamented that five years had passed since they last gathered to sing together.

Curiously, all the musicians at the table associated the couplets of banquet songs with traditional Adyghe culture, even if they were in Russian. And despite the bandit theme of some songs, primarily it was not thieves and the tumultuous 1990s that they discussed, but the Caucasian War, the problems of globalization, and the preservation of traditions. That is, the content of the songs was not that important in itself—the references to the traditions of the epic and the general mood were of far greater importance. As became clear from conversations with its connoisseurs and performers, Circassian chanson is reminiscent of Greek rebetika—song-based folklore inspired by criminal circles and the urban poor. For a long time, the Greek state did not recognize rebetika as a genre worthy of documentation or preservation, but today it is a growing tradition that has become well-known far beyond the country’s borders.

Ulyap songs might have enjoyed a similar destiny, but most of today’s performers are attempting only to preserve their musical traditions and are doing almost nothing to develop them. And for academic ethnographers and young folk enthusiasts, there are more attractive genres—from the Nart sagas of the Caucasus to songs from the times of resistance to Bolshevism and the White movement in the Russian Civil War.

Ulyap tradition has, however, seen some development in the realm of pop music. A number of pop stars, many of whom began their careers on the folk stage, set these village hits to a beat, creating turbo-folk hits that were popular all over Russia. Echoes of Ulyap chanson can be heard in the music of Magamet Dzybov or Azamat Bishtov. And it’s important to note here that even under the spotlights of the big stage, this unpolished, coarse manner of performing street songs, as well as their traditional musical basis, have been preserved by Adyghe pop stars.

Ulyap chanson and those who perform it, like Yura Negoyev, are the best confirmation of our initial assumptions: although the boundaries of “folk music” and “other music” are blurred, musical thought and the aesthetics of tradition are capable of turning any elements of musical culture into a part of their heritage. One of the biggest hits in the genre is the song Aminat. The lyrics vary from performer to performer, and depending on the context, the sound also changes: during a banquet, it is a blend of Adygean folk melodies and late-Soviet love songs, while on stage, it is an ordinary pop hit.

All photos by Bulat Khalilov and Nikita Rasskazov