Wang Tuo works with film, painting, and performance to examine the delicate interconnections between contemporary human life, myth, and history. Specially for EastEast, he spoke about his artistic project and its personal and social contexts. Wang Tuo’s recent film Tungus invites you to the borderland between several different spaces and times. EastEast was showing it from May 27th to June 15th.

Tungus is commissioned and supported by the Power Station of Art, Shanghai. It is part of the 13th Shanghai Biennale: Bodies of Water.

Right now, my work is focused on the northeast part of China, which is where my hometown Changchun (长春) is located. I’ve been staying here most of my time for the past few years, working on a series called The Northeast Tetralogy. It is a series consisting of four films and I’m now finishing the fourth one. The entire project keeps growing with time. In 2017 I moved back to China and returned to my hometown. I had left it around 2009 and moved to Beijing to do my Master’s there, and after that I went to Boston and New York. It’s quite an adventure for me, to recognize the situation in China anew, to get familiar with my own hometown. It’s like when you knew someone before and years later you realize you didn’t know him or her that well. Then suddenly you have an opportunity to re-introduce yourself, to get to know that person again— and you see how complex they really are.

I’ve traveled a lot in the northeast part of China and got to know a lot of different people, to live with them, to develop relationships. I was wondering, how am I to describe what living here means? How am I to start this whole project? 2018 was the year when Zhang Koukou killed three people in revenge for his mother’s murder that had taken place twenty two years before. When I read that in the news, I was quite shocked. This man immediately turned himself in to the police. And this entire incident reveals precisely the type of heroes we had before, in Chinese history and literature. Nowadays, China has advanced technologies, but deep in people’s hearts and minds you may still find something that we may call traditional, something that is different from the value systems of the West. This makes one see that Chinese society is extremely complex.

The first chapter of the Tetralogy, Smoke and Fire (2018), is dedicated to the story of Zhang Koukou. The second chapter, Distorting Words (2019), is a sequel, in which several times and spaces overlap, and the execution of Zhang Koukou intersects with the death of Peking University student Guo Qinguang during the May Fourth protest of 1919May Fourth protest of 1919A protest and an anti-imperialist political movement that opposed the Chinese government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles that allowed Japan to retain territories in Shandong. It grew into a broader New Culture Movement of 1915–1921 that fought against traditional Confucian values.. The third one is Tungus (2021), the work we are showing here. I’m now completing the final touches on the fourth chapter, Wailing Requiem—it’s a story preceding Zhang Koukou’s revenge, in which his long-distance communication with his former roommate is intertwined with the apparitions of the last emperor, PuyiPuyiAisin-Gioro Puyi (愛新覺羅 溥儀), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967. The last emperor of China, the eleventh and final Qing dynasty ruler forced to abdicate in 1912.

, Kawashima YoshikoKawashima YoshikoKawashima Yoshiko (川島 芳子), Aisin Gioro Xianyu (愛新覺羅 顯玗), 24 May 1907 – 25 March 1948. Qing dynasty princess of Manchu descent, raised in Japan. She served as a spy for the Japanese Kwantung Army and Manchukuo during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

, and Park Chung-heePark Chung-heePark Chung-hee (박정희), 14 November 1917 – 26 October 1979. The third President of South Korea.

.

Four years ago the project seemed to have a beginning and an end, but now I realize that it’s a black hole. It requires looking at the entire history of Northeast Asia. I’m now a prisoner of this black hole and these four chapters have only been a start. After I finish them, I’m going to take a break and clear my mind before diving back into the history of my hometown, which is linked to the history of the whole region. This is something that is fated. This is something I cannot run away from.

The background of Tungus is the Chinese Civil War and the siege of Changchun in 1948, which is a super sensitive historical incident—for the Communists and the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) alike. Changchun, the former capital of Manchuria, was held by the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China wanted to take it as part of its liberation war strategy. Since they didn’t have enough military force to do so, their plan was to circle the city, to siege it. The siege lasted for more than six months, no one could get in or out of Changchun—which means there was no food supply either. The Kuomintang government wanted to let the citizens leave so that their army would have enough resources and could continue fighting, but the CPC wouldn’t let anyone out, as they wanted the citizens to fight for food with the Kuomintang. There was formed an intermediary circle, a ring around the city, with tens of thousands of people stuck inside it, starving to death. This history is not included in our textbooks.

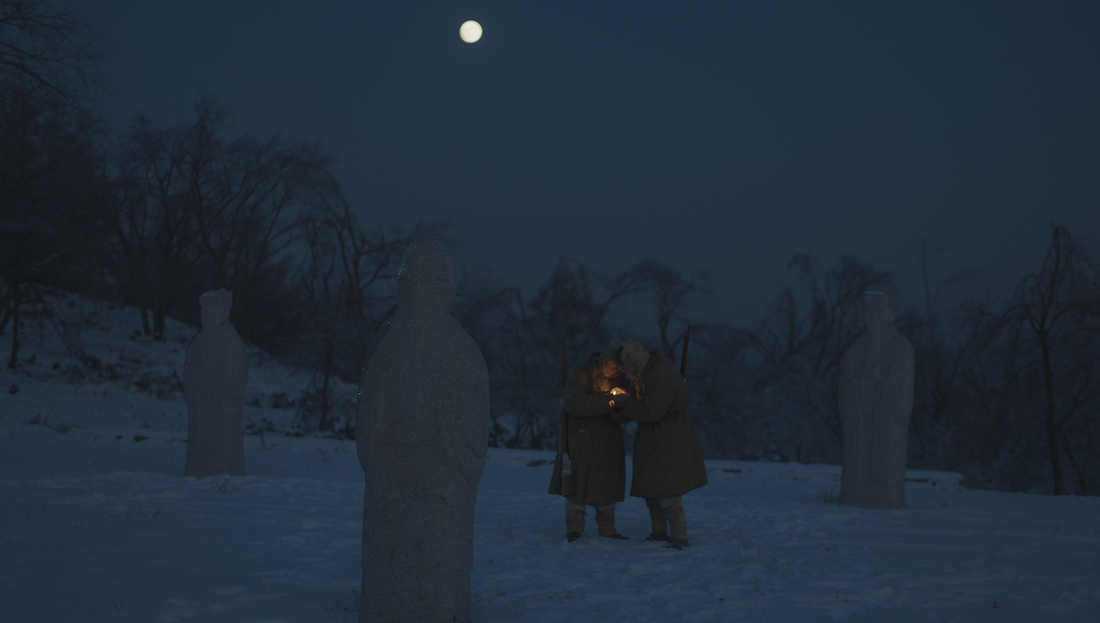

In the film, you can see two Korean soldiers. In some archives, I found the information that the CPC was not even using the Chinese army at those main blockade points. One speculation about this strategy is that Chinese soldiers wouldn’t be able to watch their own people starve and wouldn’t be able to carry out the operation, so they used a foreign army. The soldiers in Tungus belong to the Korean Independent Division. They are trying to flee Changchun. Around the same time, in 1948, there was a parallel history unfolding in Korea—the Jeju uprisingJeju uprisingDuring the Jeju uprising that lasted from April 1948 to May 1948, residents of Jeju Island were protesting against the division of Korea. Between 14,000 and 30,000 islanders were killed and another 40,000 fled to Japan.. There was basically the same thing taking place, the civil war, during which many citizens were killed. It was only in 2000 that the South Korean government released the archives that deal with this incident and gave people a chance to talk about it in public. The two Korean soldiers in the film are from Jeju island—that’s why they want to flee the city of Changchun. It is not really that far from their hometown, so they are trying to go back and try to save their families. But eventually, they find out that they cannot get out—it’s as if they were in a maze. That’s because the consciousness of the countless starving people transformed the geology, it transformed space and time.

Another important narrative of Tungus is the story of intellectuals. The whole Northeast Tetralogy has one important hidden layer, which is the question: how do we, Chinese people, reflect on the May Fourth Movement of 1919, the New Democracy Movement? How do we consider the country’s changes over the past one hundred and two years? The young students in white clothes that you can see in the film are part of these events. You can also see an elderly intellectual in black, based on the late Ming Dynasty philosopher Li Zhi—he travels to 1919 and sees the students that he used to fight with before. Everything that appears in the film ends up being his illusion, it’s only him who is real. He was lying in his bed the entire time, too hungry to move. Everything that was happening was a hallucination caused by starvation. In this hallucination, he has a choice to end it all, to kill himself by hanging. The very moment of his suicide in the hallucination is the moment of his real death from starvation.

To me, what’s most important in this whole process is being able to transform the experiences of Northeast China and my own personal experiences into something abstract. It is important to let the understanding of our complex history emerge from our intimate daily life, as well as place the ideas from history back into it. My stories provide people with access to different times and spaces, and you don’t need any particular historical background to reach them.