Smithsonian Institution

I

The quarantine has, in an astonishing fashion, turned us into impromptu sociologists of the everyday life. It has, with its considerable power, impacted what was mundane, causing us to reflect en masse on the new ways in which we organize and structure our lives. The most notably problematized element here is the home, which we have discovered anew. Our constant presence within four walls, working from home, as well as distance learning for our children, have redefined our home, forcing us to reconsider its arrangement and reconfigure its space for new tasks, such as setting up a work office with an acceptable environment for video-conferences, dedicating a space for exercising, and so forth. Home has suddenly become densely populated, its social space congealed, as not only family members are present constantly side by side with us, but also neighbors who have, just as us, been self-isolating and reminding us of their presence through various means. It is as if home has stopped functioning as an exclusively private space; it's been filled with new hygiene practices and acquired new meanings related to safety. It has become a kind of shelter, where the front door is a boundary or portal into a dangerous world.

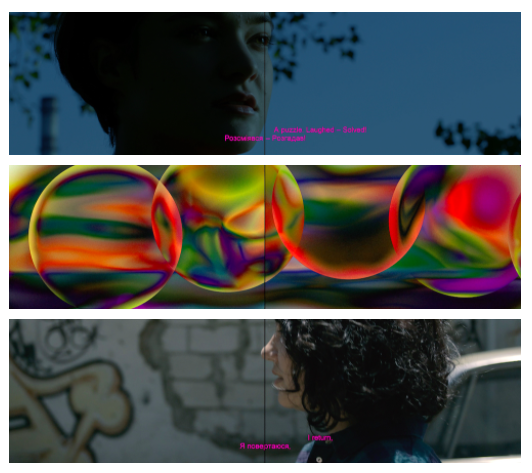

The experiences and feelings caused by restrictive measures do not only give rise to new topics of investigation, but allow us to return to the old, to revise them or look at them from a new perspective. For me, the migrant home—a subject that I had previously investigated with my colleague Olga Tkach—became just such a topictopic“Dom dlya Nomady?” [in Russian, “Home for a Nomad?”] (co-authored with Olga Tkach), Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research, № 3, (2010): 72−95.. While self-isolating in my old St. Petersburg flat, I have often directed my thoughts towards my friends and acquaintances, my informants—migrants from Central Asia, who came to St. Petersburg to make a living. How are they faring during quarantine? Do they feel confined or could they redefine and normalize their situation? Did they return home to Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan or did they stay home in St. Petersburg? How did they reorganize their everyday life? Did they even see a need to do so? I find answers to these questions to be important from the point of view of research, since migrants—modern nomads—are constantly, as it were, living in the mode of reassembling their home.

II

“Nomads”, “roamers”, “highly mobile people”—this is only a very short list of possible names given to contemporary migrants. They are all people for whom migrations are “thinkable, feasible, and even profitable”“thinkable, feasible, and even profitable”Xiang Biao, “The Making of Mobile Subjects: How Migration and Institutional Reform Intersect in Northeast China”, Dialogue, 50, (2007):70. and movement is naturally embedded into their life projects and trajectories. The contemporary migrant is very mobile: not only do they move across space, but they also radically change their entire life, time and again altering and renewing their place of work and residence, their support networks, and so forth. For them, mobility becomes the answer to any challenges, any changes in structural conditions and biographical contexts. For instance, my informants—migrant workers from Central Asia, who had come to St. Petersburg for a living and whose life trajectories we had followed for five yearsyearsThis essay is based on materials gathered within the framework of a project “Transnational and translocal aspects of migration” (“Транснациональные и транслокальные аспекты миграции”). The project was realized at the European University in St. Petersburg in 2015-2019 under the guidance of S. Abashin and with financial support from the Russian Scientific Fund (РНФ).

could, in the two months in which we didn’t see them, “go home for good”, in order to then quickly return, changing their sector of employment, their sexual partners, and so on. Such a nomad realizes an entire repertoire of life projects simultaneously, while at the same time invests in all kinds of scenarios with the expectation that one of them will definitely work out, turning out to be the most acceptable and fortunate. Let’s take the example of Rakhmonbek, a migrant from Tajikistan: he is investing money into building a house in his homeland, expecting to eventually return, applying for Russian citizenship in order to stay in the Russian Federation and simultaneously gathering information about possible migration to Sweden. His strategies are not at all unique: most of my informants, just like most of my colleagues, live in this mode of multiple life projects.

Migrants move along poorly-structured trajectories, and we could instead talk about a certain circulation between various locations, where they temporarily stop.

Researchers note that considerable changes are taking place in the phenomenon of migration itself. Currently, immigration (moving from one place of residence to another) and labor migration are ceasing to be the dominant migration scenarios, with other kinds and types of migration becoming more widespread: for instance, climate migration, where freelancers move to warmer countries during winter; migrations of retirees who, in order to maintain their previous living standards in the face of shrinking income, change national contexts; or academic sabbaticals as practices of temporary leave from the mundane in order to search for creative inspiration. The causes of migration change; they usually either have a mixed character or are not determined at all. Thus, young people coming en masse from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan to Russian urban centers to make a living do not only actualize the scenario of a guest worker, in the frame of which one’s entire migrant life is built around labor activity. They are often also actualizing a scenario of adventure, related not as much to their desire to earn money, but to acquire new impressions and experiences or form a new circle of contacts. I quote my research diary:

It is a pleasantly cool evening in Dushanbe. It is dark. You can still hear the trickle of a fountain, not yet turned off for the night. My colleague and I are sitting at an outdoor cafe, discussing the events of the day. At a neighboring table, a noisy crowd of men are speaking Russian loudly, which attracts our attention. They are discussing work trips to Russia. A young man, clearly the expert in the group, tells his friends rapidly and effusively: “Right now, in Moscow, on Sparrow Hills...” He makes a short pause, trying either to remember or to better, more vividly, formulate what is happening on Sparrow Hills. “...chicks are dancing topless!” His voice is laden with all of hidden joy, pride of his involvement, and provocativeness towards the group. “Imagine—money there flows like a river! There, you can spend in one evening—just one evening—8 thousand rubles in a club...well, what is it to them?! They have it...” His story ends with regret: “Ah, if only I could be in Moscow now...” The crowd is silent. In this silence, their unity is felt: “If only they could all be in that Moscow, so fabulously and impossibly beautiful! (July 2017)

Contemporary migrations are not linear displacements from one place to another. People do not follow strictly fixed routes and their movement does not take place between the so-called “sending” and “recipient” societies, in which they stay for a long time. Migrants move along poorly-structured trajectories, and we could instead talk about a certain circulation between various locations, where they temporarily stop.

The peculiarities of contemporary migrations are related not only to movement as space, but to a special kind of time flow for the migrants—a flow which we can designate as “extended temporality.” On the one hand, the migrant carries out short-term life projects with concrete goals—marriage, building a house, providing education for children. On the other hand, the goals change, getting intertwined with one another, and migration ends up being long-term, despite the short-term character of those life projects. This temporality could last years or decades and its boundaries are not set. Furthermore, migrants live in an “instant time”, the concept of which has been discusseddiscussedZygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge, MA: Polity, 2006), 123-129. by Zygmunt Bauman. The peculiar character of this time is, among other things, related to its concentration in the present: the life of a migrant is instant in the sense that it unfolds in the here and now, he is practically beyond the past and the future, as they are taken outside the limits of actual, instant life. The past drifts away and is barely related to what is unfolding in the present, while the future is blurry and almost entirely unformed due to the short-term character of charting life projects. It is localized beyond the limits of migration and appears where this latter will probably end. And yet, migration does not have any kind of precise ending.

Investigating changes in the constitution of a home, as well as the practices and senses related to it, bring us closer to understanding the social transformations unfolding in our communities

The above are merely some contexts and benchmarks required in order to understand the peculiarities of the migrant home: how it is created, which social sense and symbolic meanings are attributed to it. I would like to claim that investigating changes in the constitution of a home, as well as the practices and senses related to it, bring us closer to understanding the social transformations unfolding in our communities. Thus, for instance, the disappearance of larders and mezzanines from our homes testifies not so much to the fact that we no longer need to stock up on supplies or to the rapid turnover of our object surroundings, but to the essence of the contemporary consumerist society. And yet, panic shopping sprees, with people buying everyday necessities, have made the question of storing all the more timely, pointing to a temporary reformatting of society from the mode of consumerism to that of the pandemic.

III

The home of a migrant is primarily a temporary home. It is a home where no future is constructed and no present unfolds. Life in “instant time” has given rise to many new forms of homes, among which are various hostels, mobile homes, co-living spaces, and so on. And although a migrant home is usually a rented property, all these new forms are present and combined within it.

It is a home devoid of things. A nomad remains a nomad: they cannot allow themselves to become cluttered with things, they do not settle in or take root. At any moment, whenever external circumstances or their personal situation change, they are ready to fold their entire life into a bag and move on:

Gulnara has kindly invited me to her place. She rents a room in a big communal apartment prepared for resettlement; the apartment is now occupied by other migrant workers, just like Gulya. The space makes an astonishing impression. The room is sterile and faceless, hence appearing uninhabited. It has practically no traces of life. Nothing is piled in a corner, nothing is awaiting its hour of sorting and tidying. There are no neat stacks of clothes or dishes. No cute trifles which we accumulate throughout our lives—souvenirs from trips, magnets, silly and pointless presents which we often receive for our birthdays and for some reason keep, photos of relatives, pictures on the walls. Not a thing. Amidst this sterility, a glass with a toothbrush looks rather bizarre. This toothbrush is like a sapling on a faraway planet, a promise of life in a science fiction film. Or rather, a shade of life. And who knows whether it will survive! This room feels unhomely and dreary. Now I understand Gulya, who had long refused to invite me over and told me that she did not really like being at her place. Her few belongings are stuffed into a bag. Her entire life, her personality, which I could have read through her room, it all is folded and hidden. Or rather, I think, it is not hidden, but not unfolded, not embedded into this space. This is not Gulya’s room, this is just a room (excerpt from research diary, winter 2016).

The peculiarities of a migrant home are related to organizing domestic life. A temporary inhabitant is practically devoid of that day-to-dayness which creates a home, they are not very involved or interested in setting a home up and outfitting it. In a foreign space, populated by multiple people, a person is embedded into a special mode of taking care of the home. In this mode, care-taking practices are dosed and limited: there is a certain roster for cleaning, and one cannot always cook when one wants to. When living in a rented place, it can be forbidden to decorate the home, thus making it your own, or you may simply not want to do it. However, I do not believe that one loses his home in the absence of a certain mundane domestic day-to-dayness; it is rather that the home changes its traditional forms and content. Now it is temporary and mobile, it can be packed up rapidly and moved around in space.

A migrant home is not a place one returns to but a place one leaves. The bulk of a migrant’s activity and his entire life unfold outside the walls of a home

A migrant home is a communal place, one where many people live simultaneously. The overcrowding of such homes stems, undoubtedly, from the desire to save money. A migrant who has moved to a new place of residence in order to make a living scales down all of their spending, sending money to their family in their homeland or setting it aside for later, along with their entire life. It is difficult to eke out some privacy in such a communal home, and one’s own space shrinks to the size of a sleeping spot. Furthermore, even this spot may not be fully yours. Abror, a migrant from Uzbekistan, who at the moment of my study had lived in St. Petersburg for six months already, told me that he is “almost never home”—in a flat which he rents with eight more migrants from Central Asia. There he has “his own spot” on the floor where he sleeps at night. During the day, when Abror is working, his spot is occupied by a guy from Tajikistan who works night shifts. And, it seems, they have not even met each other.

The migrant home does not become a place of residence for a single family. The social bonds which bound those living in a migrant home can be constructed on starkly varying grounds, and their constellations are surprising and at the same time very understandable:

Gulnara is from Uzbekistan; she is a widow. She has three adult sons; they stayed home, unemployed. Gulnara is in her early fifties. She is a little uncomfortable with her age and with the fact that she is the migrant worker in her family, not her children. Gulnara’s room is long and narrow, around 1.5 or 2 meters by 5 meters. It has two folding beds and two large checkered oilcloth bags, the kind that were typical for shuttler traders in Russia in the 1990s. The second folding bed is for a young man from Tajikistan. Gulya said that she felt sorry for him: “He can’t live with his older brother, the brother’s got a family. So he lives with me, to me he’s like a son...” Taking on a roommate is an attempt to overcome the loneliness of which Gulya speaks of so often. The need to take care of someone is quite consistent with rational considerations—renting a room with another person is twice as cheap (research diary, winter 2016).

The migrant home is contracted not just spatially, but also functionally. When asked what he does at home, Abror answered that he comes back from work, takes a shower, eats dinner, and goes to bed. Before falling asleep, he goes on his phone—to call family, use social media to talk to friends, who are migrant workers just like him, to watch films. In the morning, Abror leaves without eating breakfast because, he says, there are too many people in the kitchen. Hence, a migrant home is not a place one returns to but a place one leaves. The bulk of a migrant’s activity and his entire life unfold outside the walls of a home—whether he is spending time at work, taking a walk in the city in search of new experiences, or surfing the internet on his phone, detaching himself from the outside world.

Smithsonian Institution

IV

Alfred Schütz wrote that soldiers returning from war in essence never return. The unique life experiences they accumulate at war stay with them, severing former soldiers from their past lives, not allowing them to return home. I think that in this case migration can be correlated with taking part in military action, although I would like to hope that migration experiences are not as traumatic. And yet, impressions of new places, of other cultural contexts, of another kind of mundanity all force you to take a fresh look at your life and redefine your own place in it. A temporary withdrawal from home life causes a kind of alienation towards it. In my opinion, the following note from my research diary, made in summer 2017 in Dushanbe, could illustrate this thesis:

Nigora went home to Tajikistan. I found that to be a bit of a pity—it was very interesting to occasionally meet in St. Petersburg and talk about all kinds of things. Now we are meeting here, in Dushanbe. I could barely recognize her. In St. Petersburg, Nigora dressed very simply, almost inconspicuously. Her hijab was the only thing that sometimes attracted the attention of passers-by. Here she is dressed in bright colors, wearing equally bright make-up. Admittedly, this way she looks rather fitting and harmonious, also in her own way inconspicuous among the equally brightly-colored clothing of the general population. We are both happy to see each other again; we share each other’s news. Nigora tells me: “I work at a hairdresser’s from nine in the morning to nine in the evening. I have only one day off every month. I rent a room with two other women. My kids live with my ex-husband’s parents.” I had heard this exact same story several months ago. Nigora had used the exact same words to tell me about her life in St. Petersburg. Now it seems to me that Nigora has never returned. She just earns a little bit less and is controlled by her family a little bit more. Nigora tells me that after her return she was ill for a long time and how much she wants to go back to Russia. She tells me that life as a migrant has changed her a great deal and that she could never be like she was before. And although Nigora has returned, I don’t know whether she could return completely (June 2017).

And yet new life experiences and models of behavior are not the only factors contributing to alienation from that home which “stayed at home”. It turns out that withdrawing from one’s former mundaneness and daily life also makes one’s former home alien. Many of my informants have told me that trips home on vacation often bring no joy—it is not easy to fit back into one’s former pace of life, immerse oneself into forgotten domestic matters, rebuild relationships with family members. The wife of one of my informants spoke of the same thing, having remained home in Tajikistan: “Things have piled up while he [husband] was away, but he has come for just a few weeks and doesn’t even want to change a light bulb, as if he is not home at all...”, snapping in frustration: “I wish he would leave soon, it is somehow more normal here without him!”

New communication technologies contract space and allow migrants to not only stay in touch with relatives, but literally live with them in real-time. I was surprised to learn that a migrant’s contact with his home and conversations with relatives in his home country are structured around the domestic everyday. I accidentally witnessed a phone call between a close acquaintance—a migrant from Tajikistan—and his wife. Rakhmonbek asked his young wife in precise detail about what she had bought in the shop that day and whether she had swept the yard. It turned out that such conversations are very frequent and represent an attempt on behalf of those who live far away from home to fit into domestic life. These conversations create an illusion of home being present and of their involvement in it. However, I suspect that these conversations have their own peculiarities, related to the selection of information and the power dispositions of participants. It appears that in this case alienation and a redefinition of home are inevitable, as it is difficult or completely impossible to return to it. The home which “stayed home”, just like the home in the place of migration, becomes somewhere you leave, not somewhere you return to.

V

It could appear that for contemporary nomads home effectively disappears. I noticed that in describing the migrant home in my research, I have formulated many things negatively, using the modifier “not”, denying it some essential characteristics and de facto counterpositing it to the home of a sedentary person. Obviously, this happens during the formation of a phenomenon, when it is first crystallized without having its own naming and language of description. Nevertheless, I would like to produce a positive formulation of the migrant home, which would better correspond to how it is perceived by its inhabitants. I would describe it as a light home. It is not merely a home which is left (without always being returned to), it is not merely a home which is easily packed into a bag or back-pack and carried around with the person. Home still exists, but it, in an astonishing fashion, is devoid of its materiality. Contemporary nomads do not reject home—it is always present in their worldview, but in this dematerialized mode.

Home is present in the imagination, in projects for the future, but its location in time and space is unknown and is instead a desired state of peace

Thus, for instance, home entered the picture in every conversation about the future. Here we must note that talking to my informants about the future has been rather difficult; in these moments the contemporary short-term character of life projects became obvious: people don’t know what is going to happen to them down the road and do not try to make long-term plans. Nevertheless, they have dreams for the future and they are all similar, which is unsurprising. Migrants connect their future to an end of movement; it begins where migration ends. This being said, this future is devoid not only of temporal and spatial dimensions. Informants have avoided questions about where exactly they would live— the future has become deterritorialized (“Well... I don’t know where I’ll be… Where will I turn up? Perhaps here [in Russia], perhaps in Tajikistan. Perhaps somewhere else. Who is to know?!” Burkhon, a thirty-seven-year-old migrant from Tajikistan). But in this future, there would always be a home, tightly related to family and symbolizing peace and prosperity: “Me in the future? [pause] I would like my own home. I sit in it, surrounded by grandchildren. All is well...” Zebuniso, a twenty-eight-year-old migrant from Tajikistan). Thus, home is present in the imagination, in projects for the future, but its location in time and space is unknown and is instead a desired state of peace.

In the present, home comes down to a number of meaningful minutiae. For some, it is photographs of family on the smartphone, for someone else—an object, which they brought with them into migration and which with time became imbued with immense symbolic meaning. Frequently, the objects or photographs are not even related to home, but a story about home is created around them. For instance, Abror, a twenty-year-old migrant from Uzbekistan, spent a long time showing me pictures of horses he downloaded from the internet on his phone, and told me about how he will earn enough money and “breed it at home.” Another example of an imaginary and symbolic home would be a case from the research practice of my colleague who met with migrants from the Baltic states in the UK. All family members lived in different places and did not meet more than once per year; that said, they took home to be wherever the family dog was at that point in time. Incredibly, the dog did not just unite the family around itself, but was a symbol of home. It became the anchor which grounds a nomad.

VI

The pandemic and life in self-isolation have undoubtedly become a challenge for everyone. The problem lies not only in the fact that rent becomes an unbearable financial burden when there is no work and not only in the congealed social space of an overpopulated home—guest workers from Central Asia live like this almost the entire time. The contemporary nomad was forced to stop—while a break in movement, real or potential, is for them more difficult than anything—and to make a choice as to where to wait the pandemic out. Specifically, national contexts and scales were made relevant. My informants faced the questions: should they stay in Russia or return to Central Asia? This question is not only and not even primarily that of where it is safer, but rather that of where one is fitting and accepted. Thus, the situation has forced migrants to determine their home. For them, home suddenly ceased to be a place you leave or a place you return to, becoming instead a place where you stop and stay for some time. In the process of forming such a home—a private space—the role of the national government, which protects and controls the individual during a pandemic, became obvious. It is difficult to say what will happen next and how concepts of home will change. Either way, they have turned out to be quite flexible: it can be seen how an apparently stable, even traditional social form like home responds reactively to any external challenges. That said, the lives of contemporary nomads actively problematize and cast doubt on the concept of home, reformatting and multiplying its senses.

Translated from Russian by Diana Khamis