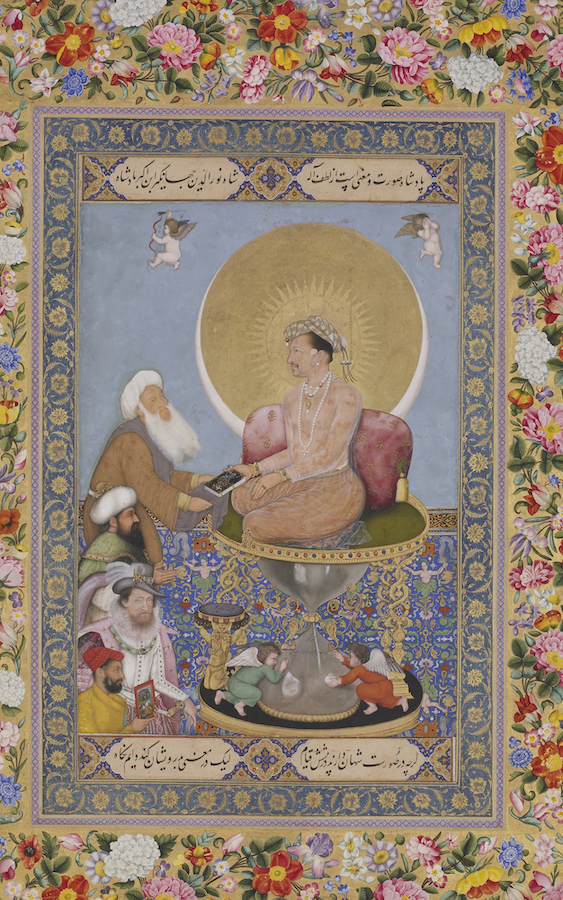

MS.5.2006 / Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

A folio from a Muraqqa album at the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the capital of Qatar, depicts the Mughal Padishah Shah Shuja (1616–1660): a profile similar to that of Roman coins, bright colors, beautiful robes, and a thin strip of golden glow around his head. Like other basic forms in visual arts and architecture, the nimbus (from the Latin nimbus—“cloud”) is found in different cultures. Europeans are familiar with it due to its presence in Christian iconographyiconographyFrom the Greek eikon (“image”) and grapho (“write”)—a system of depicting protagonists or stories characterized by the creation of art forms with a permanent meaning., where it most often indicates holiness (in some cases it was used to emphasize a high position of its owner, for example, a princely or royal status). But you can also come across the nimbus in Islamic art.

Like any generalization, the word combination “Islamic art” is problematic, since in almost every instance representatives of different Muslim cultures have brought something of their own, something local into their arts. Here are just a few examples of the use of the nimbus as a part of this tradition. Islam originated in the 7th century on the territory of Western Arabia and quickly became a state religion of the Caliphate, formed after the death of Muhammad. In the second half of the 7th century, the Arabs conquered the Sasanian Empire (226–651), which existed on the site of modern Iraq and Iran, whose population was mainly Zoroastrian. A new art language cannot arise out of nowhere—Muslim art, for example, was influenced by the Sassanian, Hellenistic, and Christian traditions. It was the Arab-Muslim conquest of Iran that brought different meanings to an old context, which in its turn led to the emergence of a new, synthetic art.

Right: Balchand. Emperor Jahangir prefers the Sufi Shaikh over kings. Circa 1615–1618

F1945.9a, F1942.15a / The St. Petersburg Album / Freer Gallery of Art

According to a popular point of view, there is a taboo in Islam regarding the depiction of people and animals. Actually, this is not true. The Quran does not explicitly prohibit the depiction of people and animals (unless they are idols), although the Quran itself is never illustrated. The art historian Oleg Grabar refered to this special attitude of Islam towards artistic depiction as “aniconism.” Nevertheless, in a number of Muslim cultures images of people and animals can still be found, although human faces in them are covered with a veil—most likely in accordance with the tendencies mentioned above.

There are many speculations about the origins of the nimbus as an art element in the Islamic tradition. According to one version, it initially appeared in Persian art. Some researchers assume it was influenced not by the Christian, but by the Zoroastrian tradition, incorporated into the Islamic visual language under the Sassanids. It was a way to express divine grace, farrah (literally meaning “glory” in Persian). The glowing glory could be emitted both by the sacred figures of prophets and angels and by earthly rulers, who, like in the Christian tradition, were considered God's chosen ones on earth. These ideas were reflected in the Mughal miniature, which owes its development to Persian influence.

The most common forms of nimbi in Islamic art are, firstly, a “fiery halo,” and secondly, a glow around the head. A fiery halo looks like flames and it is important to note that they can surround the entire figure of the hero. It often can be found, for example, in the story about Miraj (Ascension) of the Prophet Muhammad.

In Mughal India, nimbi first appeared in the works of art created at the court of Padishah Akbar: it was then that the Mughal book culture was flourishing. Kitabhane—book workshops where mastersmastersNakkash, or musavvir, is a word for an artist or calligrapher. Likewise, Nakkash, or Musavvir, is the name of Allah in Persian culture. produced and kept manuscripts—became the center of illuminated manuscript production. Akbar’s own library alone contained about 24,000 volumes with Iranian, Indian, and Central Asia immigrant artists known to be working at the Padishah’s court. Bringing together the artistic traditions of numerous nations, they created a unique style of Mughal miniatures and portraits in particular.

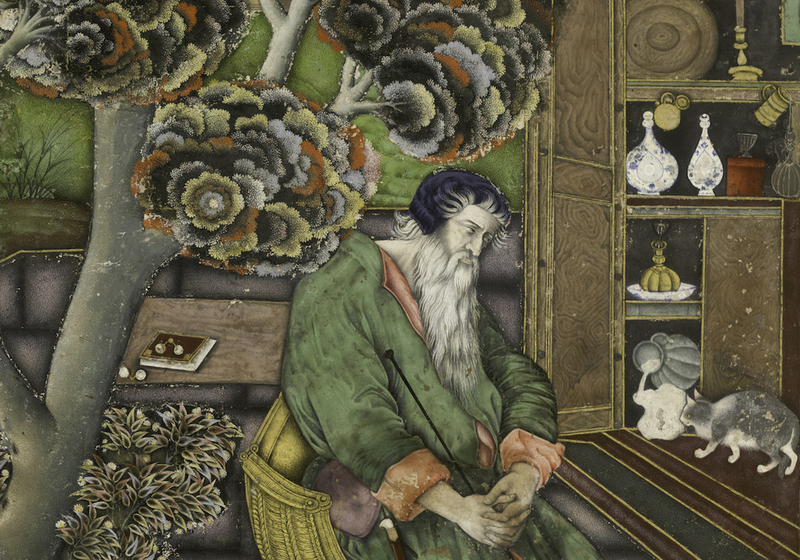

MIA.2014.325 / Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Right: Balchand. Portrait of Emperor Jahangir. Circa 1620s

MS.771.2011.1 / Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

It was under Akbar when the first images of the padishahs surrounded by a golden nimbus actually appeared, and the ritual of worshiping the emperor, known as darshan (from Sanskrit “viewing a saint or deity”), was born. So, that was how the idea of the blessing ruler was spread. Soon, the nimbus became an element that also was a characteristic of the saints: it matched the concept of divine grace Muslims were familiar with—baraka. Mughal book miniature is one of the main genres of artistic expression where anthropomorphic images and, accordingly, nimbi can be observed. But it is difficult to describe it as purely Muslim: Akbar created a syncretic religion that incorporated the main tenets of Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity—Din-i Ilahi (“divine faith”). This doctrine, however, only outlived its creator for a brief period: subsequent padishahs were Muslims and spread both Islam and Muslim art around Mughal India.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich