Olga Kononova and Oleksandr Burlaka employ serious research methods to develop a playful narrative about the eccentric residential architecture of the Ukrainian seaside settlement Zatoka—the materialized dreams of an affordable riviera. This is one of the three winning submissions to our Dream open call.

Very often, people born near the sea would prefer to live closer to the water. The sea can become a big part of childhood memories, along with sunburns, jellyfish lying in the sand, the smell of seaweed from the water, diving in to search for stones or mussels, jumping with a big splash. Consequently, the experience of the sea influences the desire to get closer, the dream to live nearby. For architects, who also appreciate this kind of neighbourship, a great interest lies in the spatial embodiment of a site-specific kind of dreaming.

Ukrainian Zatoka, an urban-type settlement in the Odessa region, is the grounds for the research of human desires. This case study focuses on informal architecture created without professional designers, with naked functional simplicity, hinting that the proximity of the sea is an element worthy of one's investment. Zatoka possesses an undiscovered layer of individual residential projects that are a representation of contemporary vernacular architecture in the Odessa region. Moreover, these projects realize the spatial fulfillment of the residents’ dreams.

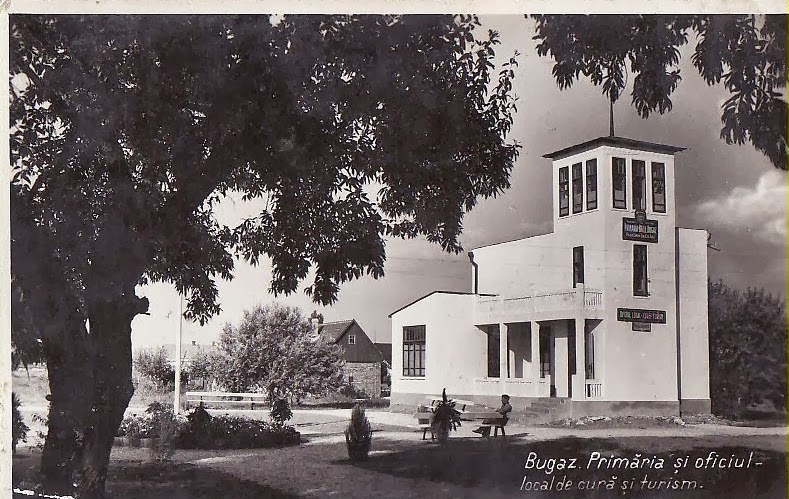

Zatoka is located on the Karolino-Bugaz and Bugaz Spits, between the Dniester Estuary and the Black Sea. It was founded on April 15th, 1838. The first evidence of settlement dates back to 1827, starting with the construction of a lighthouse. The area has a sand beach that is five kilometers long and fifty meters wide; consequently, Bugaz Spit was developed into a resort. Before 1903, Zatoka was a deserted landscape of sandy beaches that was inhabited by fishermen in summer. In 1915 there was an orphanage, sanatorium, and around thirty private summer houses. The unique features of the Bugaz Spit were noted by the League of Nations Health Organization, which financed the construction of the tuberculosis sanatorium, which helped Romania in dealing with the disease. The sanatorium is still functioning. Children with disease of the osteoarticular apparatus, nervous system, and upper respiratory tract are treated there. Zatoka was called Bugaz, which was a part of Bessarabia—the historical region—and its territory had been in union with the Kingdom of Romania since 1918. In the summer of 1940, the Romanian government agreed to submit to the Soviet Union demands proclaimed under the threat of war and to withdraw from Bessarabia, allowing the Red Army to annex the region.

Courtesy Olga Kononova and Oleksandr Burlaka

Today, Zatoka has a population of 1,781 people (according to a state statistical survey dating January 1st, 2019). Three territorial districts number over 180 hotels, guest houses, and recreational centers. Even though the area is packed with a resort infrastructure, there are individuals and families who call Zatoka their home. Judging from the new construction present here and there, people are still interested in having private estates there or in making money by building houses for buyers interested in the region. Zatoka has another distinctive feature— a significant scarcity of areas where construction is permitted, especially close to the seashore. Nevertheless, most of the existing buildings are being squeezed into this space, which forms the residential blocks filled with atmospheric references.

The area of main interest is the densely built and populated residential blocks spread unevenly throughout the Bugaz Spit. These particular blocks resemble many different places in the world. It is possible to encounter the vibe of the low-rise residential part of the Harajuku neighborhood in Tokyo while passing knots and webs of electrical wires, external stairs encircling the structures, clean plain facades, and utility pipes set outwards. Or feel the laid-back atmosphere around the handful of boathouses at Channel street in San Francisco due to the variety of colors, window shapes, and boats parked near the private piers. And, finally, to find yourself inside Venice’s corridor streets, wittily spotted by Giulia Foscari in Elements of Venice. Similar to her observations, narrow streets dividing the houses create the system of an external element that is essential to the place. Purely functional in use, these corridors are physical dividers of private properties and sometimes get as narrow as is possibly allowed. This solution saves scarce and valuable square meters. Site-specifically, these streets also lead you to the “grand finale” of the walking journey—to the sea or waters of the estuary.

It is worth mentioning how residential buildings appeared in Zatoka in the first place and how residential houses differ in orientation. Zatoka is washed by the Black sea waters from the Southeast and is facing Dniester Estuary, which is on the Northwest side of the settlement. The train tracks divide the Spits into two parts: the southern part that faces the sea and northern part that developed towards the estuary. The physical barrier of the tracks influenced the functional division of the settlement. During Soviet times, the northern lands were assigned to “gardening partnerships,” which belonged to research institutes, factories, or plants, and the land plots were divided between the employees. The seashore of the Black sea also had land plots assigned in the same manner, but institutions would formally create “dacha cooperatives” and employees would receive light wooden houses on the beach of the Zatoka.

After the Soviet Union collapsed and the process of privatization took place, each former member of the cooperative or partnership would try to become the owner of the land or the owner of the whole plot, depending on the side of the tracks. Currently, a significant part of the residential houses is located on the shore of the estuary. Most of the seashore is occupied by hotels and recreational centers, based on commercially driven decisions and the sneakiness of the former owners. Despite the competition for the southern side, residential houses also found their way to the beach, finding their spots in cracks of capitalism. Nevertheless, both orientations have appealing features. Dniester Estuary neighbors have the opportunity to fish for a generous variety of species or collect crayfish. On the romantic side, this location has views of the beautiful sunsets. The owners of the houses facing the sea get their salty breezes, get to meet both the dawn and the packs of tourists that congregate on the sand during the summer season. Both sides have the same feature—all balconies and windows face the water. Most of the houses are rectangular in plan and up to three stories high, all with balconies and external staircases. A lot of the houses are light and used seasonally but by virtue of the local climate they provide a cozy hideaway from May until the end of October, having unconditional market value as homes with a sea view.

Oleksandr Burlaka's personal archive

Elements of Zatoka

Following the idea of the 2014 Venice Biennale: Elements of Architecture, residential houses in Zatoka can be deconstructed into a range of elements, some of which are specific to the place.

Water is obviously an essential part of the space and the original reason for most of the construction. Water is a source of calm, fresh salty air, food, and fun. The infinity pool at arm’s length. A symbol of rebirth and purification. Dare to say, that all of the spatial decisions are being made with concern to nature, its benefits, opportunities, and limitations.

Facades are presented in an absolute functional role: as a divider from the whims of the weather, possessing little aesthetic or cultural investment, but mostly organizing the relationship between the private space of the resident and the open space that is focused on seaside activities. Curtains as opposed to curtain walls became a part of the facade, providing privacy and opening quickly when needed.

The window embodies not only an object providing function but a destination, since it gives uninterrupted views of the surrounding which are so rare in the urbanized world. People go to a window to look outside at the sunset or starry sky, to breathe a salty breeze, to hear the sounds of the waves, and splashes of the water, to check the weather and decide on their daily routines—as activities also depend on whether the sea is calm or choppy.

External staircases are used as many times as there are houses in Zatoka. Practically, it saves a lot of space inside the house, so there is more space available for use. The outer stairs allow for private entrances to the rooms on each level, so the owners can rent out the premises without disturbing their own private life. At the same time, external stairs can be seen in historical photos of Zatoka, depicting a few local residential houses from that time. Probably the practice of building houses this way was inherited and can be considered a local typology.

A balcony is present in all of the buildings and has as essential function to the place as external stairs. Both private and public, a balcony—an element with multiple expressions and purposes across architectural typologies and history—here in Zatoka plays the role of a viewing platform, allowing both inland and seaside houses to have a view of the waters surrounding the settlement. If the house is located farther from the shore, the height of the structure is increased to place a balcony that affords an unobscured view towards the horizon. The occasional house that has the misfortune of no view will still have a balcony. The types of balconies are very different and have no visible pattern—from light wooden structures to a stone attachment to the facade, it all depends on the resourcefulness of the resident.

Private piers are a common element of the houses facing Dniester Estuary. The pier defies the use of the space, creating a platform for endless programmatic opportunities, and appears to be the most important part of the house, the place with the highest concentration of activities. Residents fish, sunbath, grill food, depart on the boat, play, read, gossip, and eat there.

Private beach—a substitute for the private pier, nevertheless, gives the glamor of luxury to the owner. Playtime with kids appears more comfortable and safe, beach parties can be organized every day, and a table with chairs can be brought there in no time in order to enjoy dinner outside. Sometimes the beach is shared between two or three houses, therefore becoming a public space and meeting point for the owners. Again, the surface of the sand provides opportunities for different uses and human interactions.

One more site-specific element of the house is the boat garage. Since the main means of transportation are boats, sometimes kayaks and floating mattresses, there is a storage space reserved for these “vehicles” in many of the houses.

Used car tires are largely used to reinforce the bank, as they dampen the shock wave effect. Encounters with this element are so frequent that they have become an integral part of the coastline landscape.

The lifestyle of Zatoka residents is arranged around the water and sea but they no longer depend on natural resources for their survival. On a calm summer day, it is easy to envision the scene from Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth when the characters of Michael Cain and Harvey Keitel are sitting in the pool watching a young lady swimming. Just the same, one has no obstacles to sit and chat near their private pier in the warm water of the Dniester Estuary, which is rumored to possess healing mud. The latest news, sadly, is that the water is polluted by the nearby settlements, dumping their wastewaters into the estuary. This disrespectful practice can be changed, as more people would like to get all the positive experiences possible in Zatoka.

Still, the open sea provides one with endless opportunities for how to spend the day, and a private house ensures the feeling of safety and comfort. The day is divided into two parts: mornings are spent near the sea—most of the residents of the estuary side would cross the island to get there for swimming. The rest of the day would be dedicated to the household and work. Activities are partly arranged around fishing and gathering mussels in the sea—a valuable commodity for the local fast-food vendors and markets. And on the other side, time is partly dedicated to slow living near the water. Sunbathing, swimming, cooking in open kitchens, sitting in chairs facing waters, playing with kids, reading books, taking pictures of the endless sky on top of the sea, gossiping with a neighbor from the adjoining pier, smoking cigarettes, having family gatherings, and drinking strong beverages—day by day living at the resort, without leaving home.

While Zatoka has this curious architectural collection of houses, the whole settlement is diverse, unevenly developed, and inhomogeneous. A significant part is built up with recreational centers, there is extreme competition for the development of vacant space and dishonest schemes for getting permits for them. However, on the side of dreaming and enjoying life, Zatoka is a place of unexpected wonders. A miniature of the city with a variety of private and public spaces, activities, and architectural elements to take on-board. As for the concept of the pier and its multipurpose potential rediscovered by locals, a more thorough case study of it might be good enough to make the foundation for a handbook that every architect designing public seafronts could refer to.

*Editor's note: As of September 2023, the locations mentioned in this text have been destroyed as a result of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.