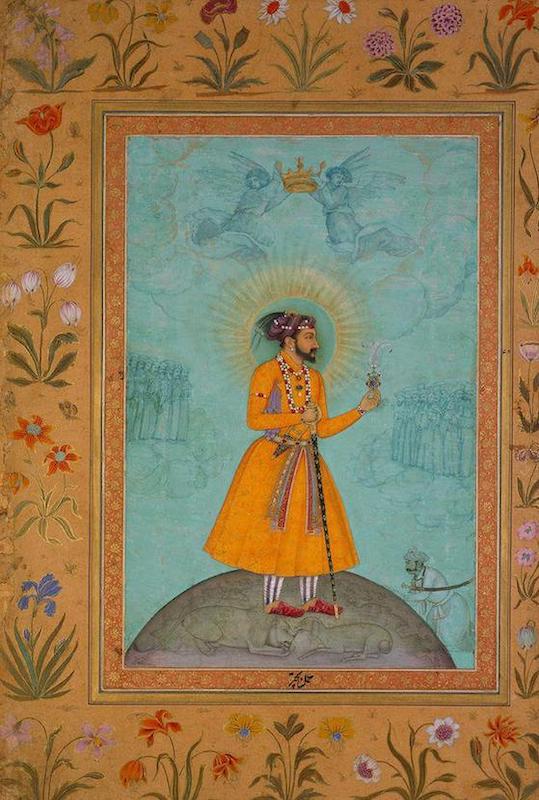

MS.44.2007 / Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

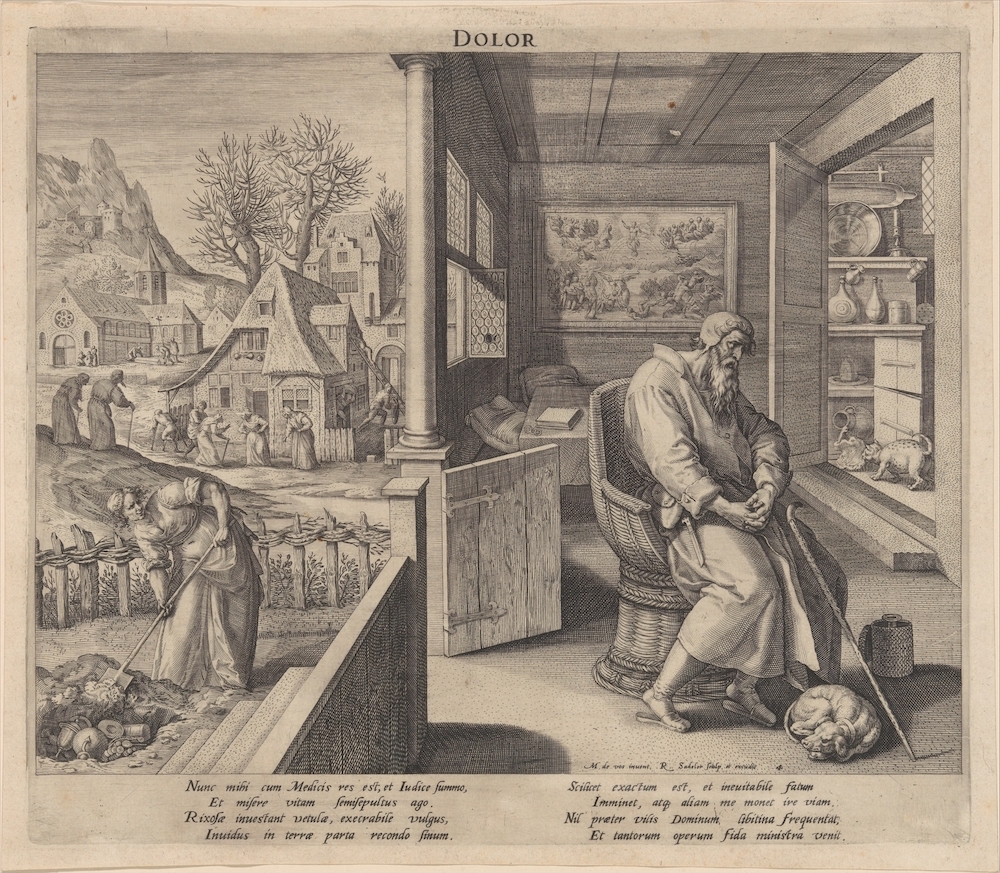

Right (fragment): Raphael Sadeler I. Dolor (Sorrow). Engraving after a drawing by Maerten de Vos. Ca. 1560-1628.

44.62.6 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

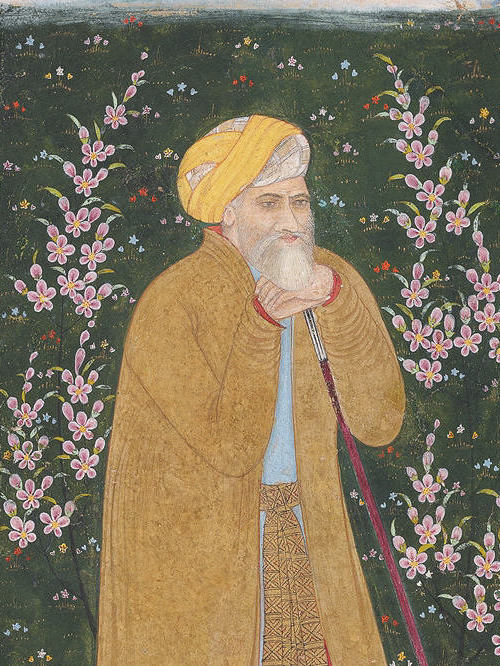

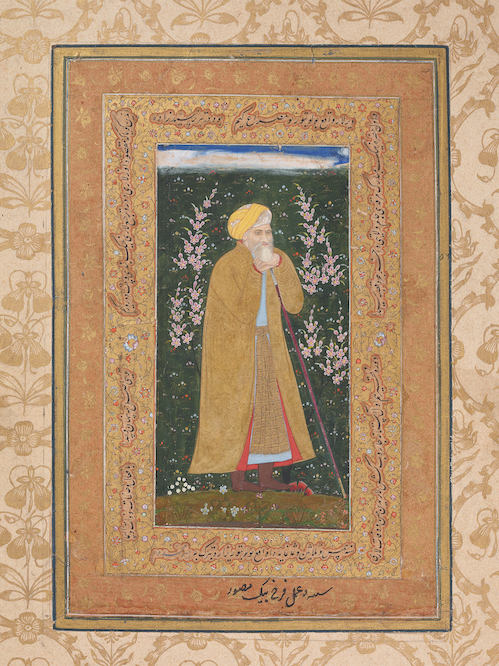

A Sufi sage, bent with age, sits in a wicker chair under a sprawling tree. His eyes are open, but his gaze seems to be turned inward. He is contemplating. A dog has curled up snugly at his feet and two sheep feeding their young lie a little farther behind him. This is the subject of a miniature by Farrukh Beg, a Mughal artist of Persian origin, dated 1615, from the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha.

A man, bent with age, sits in a wicker chair on the porch of his home. His eyes are open, but his gaze seems to be turned inward. He is contemplating. A dog has curled up snugly at his feet and behind him, outdoors, the life of a small Flemish village runs its course. This is the subject of an engraving, Dolor (Sorrow), made by Raphael Sadeler, a member of the largest North European engraver dynasty, made after a drawing by Flemish master Maerten de Vos in 1591.

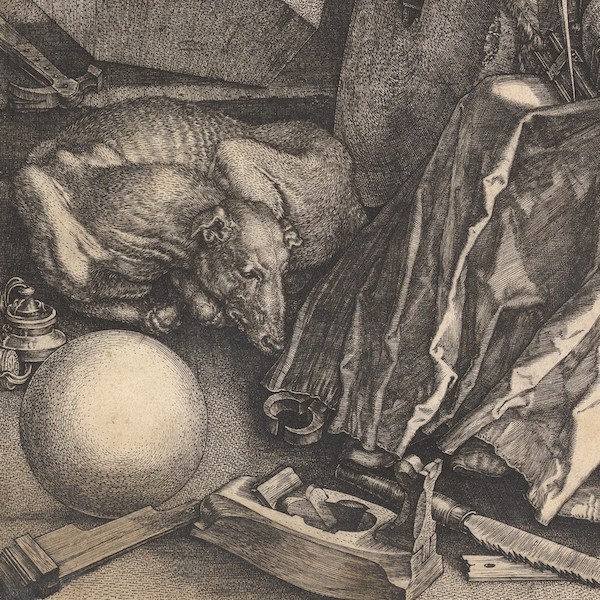

The similarity between those two images is no accident: Sadeler’s engraving served as a model or blueprint for Farrukh Beg’s miniature. The original drawing by de Vos is furthermore inspired by one of the most famous engravings in European history—Albrecht Dürer’s Melancholia. The curled-up dog, symbolizing melancholy, the thoughtful posture of the old man, the thin staff or walking stick on which he leans, and several other objects have all come into the Eastern miniature from Melancholia.

How did a Flemish engraving end up in Agra, at the court of the Mughal EmperorMughal EmperorThe Mughal Empire was a Timurid state, which existed on the territories of contemporary India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and southeast Afghanistan in 1526-1540 and 1555-1858. where Farrukh Beg was working? European art mainly entered India by way of the Dutch East Indian company, which was founded in 1602 and was given monopoly rights to trade with many countries of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Engravings and illuminated manuscriptsilluminated manuscriptsIlluminated manuscripts are medieval manuscripts where the text is accompanied by certain pictorial elements: borders, miniatures, etc. These manuscripts were termed "illuminated" because initially they were decorated with thin gold plates.

were also brought to the region by Jesuit missionaries. Thanks to traders and religious figures, the local masters could get acquainted with Western notions of perspective and realistic painting. The practice of adapting European artistic techniques was widespread among masters at both SafavidSafavidThe Safavid state existed from 1501 to 1722 and encompassed the territories of contemporary Azerbaijan, Iran, Armenia, Georgia, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, eastern Turkey, Kuwait, Bahrein, as well as a parts of Pakistan, southern Uzbekistan, eastern Syria, and southern Russia. In medieval sources it is often called the Qizilbash state.

and Mughal courts, but it is not known what criteria the local artists used to choose the miniatures and how the miniatures would then be copied.

1978.38 / Cleveland Museum of Art

Right: Bichitr. Jujhar Singh Bundela Kneels in Submission to Shah Jahan (detail), 1630–40.

07A.16 / Minto Album, Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library

The intercultural influence was mutual. Mughal and Safavid illuminated manuscripts were brought to Europe, where they changed the depictive techniques of Western painters. Rembrandt, for instance, copied works brought from the Mughal empire. The folio with Farrukh Beg’s miniature was part of a muraqqa, a miniature and calligraphy album meant for close examination, which often ended up in the collections of Eastern aristocrats. The first muraqqas appeared in Persia in the XVI century, and in the beginning of the XVII century they became widespread in the Mughal and Ottoman empires. According to some scholars, albums became popular in Europe as a format because of the muraqqas brought by British colonizers from India. Unfortunately, most muraqqas were lost, broken up, or split apart into separate sheets: this practice made selling them easier and more lucrative.

The aforementioned miniature is the only surviving work of Farrukh Beg for which a European model was used. It is unknown why the master chose to copy that particular sheet from The Four Ages of Man, an album by Maerten de Vos. By 1615 Farrukh Beg had turned seventy. Yet another of his surviving miniatures dates to that very year—a self-portrait. This allows some researchers to associate the old, white-haired Sufi sage in the first image with Farrukh Beg himself.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

It is also remarkable that this miniature retains most of the elements present in Sadeler’s engraving, although they do change their location. The main subject, the Sufi, moves from the house to the outdoors, under a tree. His table, with a book on top, is now also situated outside. The pince-nez, depicted on the engraving, remains part of the miniature but is multiplied: instead of one, Farrukh Beg places two pince-nez on the table. The clothing of the sage is practically the same. The objects of decor inside the house remain almost identical. Even the cat, spilling a jug of milk, moves from the engraving to the space of the miniature. The only change is that Farrukh Beg adapts common European objects to a local context: the jars on the shelves change their shape, reminding one of huqqa—Mughal hookah vases. These were made from metal or beautiful colored or transparent glass, produced in the Mughal empire.

Despite the apparent similarity in composition between the engraving and the miniature, Farrukh Beg ignores the laws of perspective which the Flemish engraving obeys: the miniatures is situated in a completely different, non-three-dimensional, abstract space. Besides that, the Sufi, first of all, is made into the single protagonist of the image (the Flemish village and its people disappear) and, second of all, is transported to a place under a giant sprawling tree. And of course, the miniature, unlike the engraving, is lushly colored, with the surreal combinations of tones characteristic of Farrukh Beg’s style.

44.62.6 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fragments: Farrukh Beg. Miniature with a Sufi Sage, after the European Personification of Melancholia. Folio from an album belonging to Shah Jahan, ruler of the Mughal Empire. Ca. 1615-1616.

MS.44.2007 / Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Fragments: Albrecht Dürer. Melancholia I. 1514.

43.106.1 / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Farrukh Beg was born in Persia around 1516. He is first mentioned as a miniaturist in the 1580’s (then he was known as Farrukh Hussein), while he was working in Kabul for the Shah Mohammad Khodabandeh from the Safavid dynasty. The next mention of the name Farrukh Beg is dated 1585, when he served Akbar, the third Mughal emperor, in India’s Bijapur. It is likely that this ruler granted the artist the honorary title of “beg.” Akbar, as well as his successor, the fourth emperor Jahangir, had a major influence on the development of Mughal handwriting and calligraphy tradition, patronizing masters and opening libraries. In 1609, in his memoirs, Jahangir called Farrukh Beg “unrivaled in his age.” The miniature with the Sufi sage was painted in Agra in North India, where the master died after only four years at the age of seventy four.

Translated from Russian by Diana Khamis