The pop version of Algerian raï music of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is well known all over the world. Cheb Khaled's songs “Didi” and “Aicha,” as well as “Desert Rose”—Cheb Mami's collaboration with Sting— became international hits during the rise of widespread interest in Arab ethnic music. However, in Algeria and other Arab countries the perception of this genre has been controversial at almost all the stages of its development due to its social context and some content that many members of Muslim communities have found unacceptable. Songs often address earthly problems and desires, including sexual ones, and raise issues of pain, frustration, and the pursuit of freedom. According to a definitiondefinitionNasser Al-Taee, "Running with the Rebels." Echo magazine, vol.5, issue 1, 2003. given by the musical ethnographer Nasser Al-Taee, by its nature "raï is a musical statement rebelling against political, social, and religious constraints." This discontent is rooted in the colonial past of Algeria and before finally acquiring its contemporary pop music sound, the form of raï had already undergone continuous transformations.

The Mediterranean port of Oran, one of the main centers of musical culture in Algeria and a place often known as “little Paris,” is considered to be the birthplace of the genre. During the French occupation (1830-1963), the west of the country where the port is located was much more densely populated by colonists than any other part of Algeria. Muslims and Jews also made up part of the city’s population and the combination of multiple diasporas, together with passengers from ships entering the port, contributed to a constant circulation of cultures that influenced each other for decades.

Wikimedia Commons

The word raï was used to describe the opinion or advice that people asked for from cheikhs, local poets-musicians in this region of Algeria. The poets expressed their opinions while performing malhun—Bedouin poetry set to music in the Darija language, a Maghreb dialect of Arabic. At that time, malhunmalhunHana Noor Al-Deen, “The Evolution of Raï Music.” Journal of Black Studies #35, 2005. was one of the two most popular genres in the region, along with andalusi—classical Arab music that came to Algeria after the expulsion of the Arabs from Spain in the 13th century. Cheikhs performed at weddings, religious ceremonies, and cafes to the accompaniment of two metal drums (gallal), a wooden flute (gasbah), and clapping hands. Through their songs, they passed knowledge of values, traditions, culture, and even politics, on to younger generations. Many cheikhs (Cheikh Hamada and Cheikh el-Khaldi being the most famous) openly opposed the French occupation, performing their songs exclusively in Arabicwhich landed many of them in prison as a result.

The economic situation in French Algeria was in a state of constant deterioration. By the 1920s one of the only ways for women from particularly vulnerable social strata— (orphans and the lower class) to survive was to make public performances with dances and songs, which was considered unacceptable for Muslim women. This is how cheikhas appeared—female performers who began to adaptbegan to adaptAndy Morgan, "Rai: Music Under Fire", 1999. male cheikhs’ style and songs, using an approach that was a shock to the poetry and music of those days. Female cheikhas performed in bars and brothels in Oran in front of men to the accompaniment of male musicians, sometimes featuring female dancers. Cheikhas were called "women of the cold shoulder" for their manner of dress, unacceptable in "decent" society. On stage, they often hid their faces with a veil and forbade the inclusion of their photos on the covers of records. Their repertoire was considered vulgar, as in their songs they talked about poverty, alienation, sexuality, the joys of alcohol, love, death, and prison. Gradually, these compositions began to be known as raï and were spoken of scornfully by many as a degraded version of malhun. In Algeria, cheikhas themselves were seen as a threat to the moral foundations of traditional society.

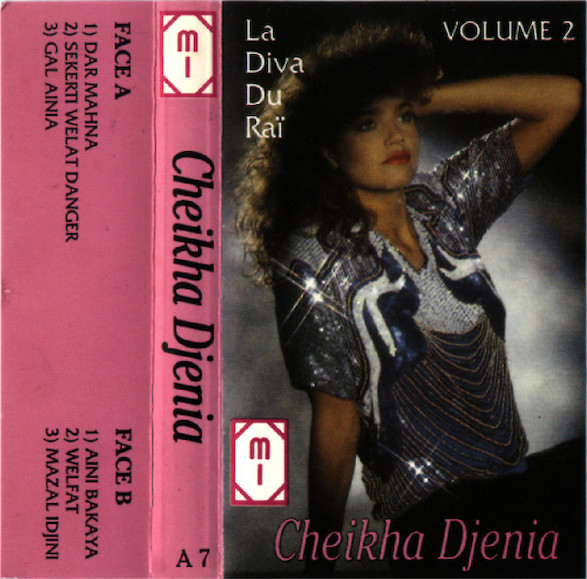

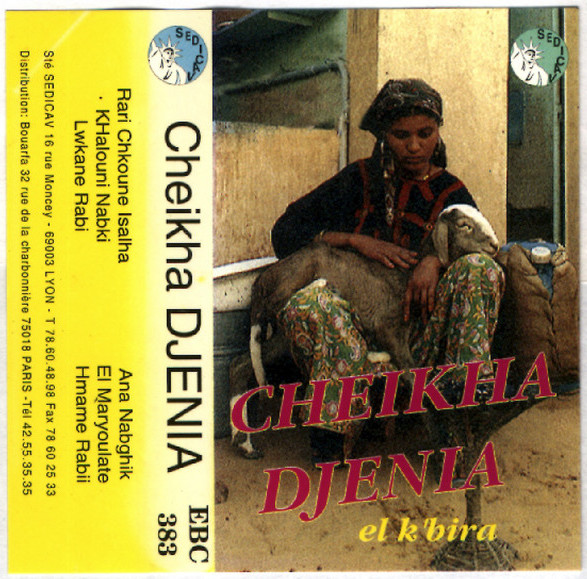

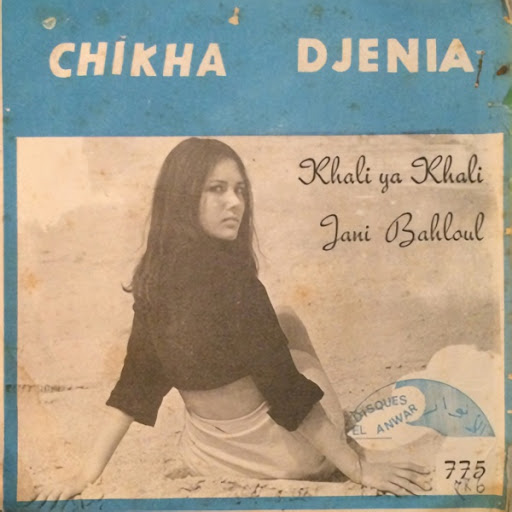

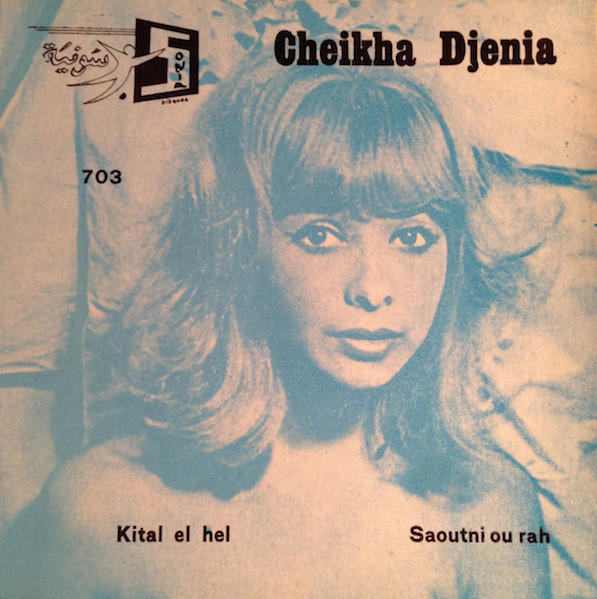

The most famous cheikha was Cheikha Rimitti. Although she was forced into becoming a performer, she is now considered the grandmother of raï music. Cheikha Rimitti was also the most scandalous cheikha, since she was the most direct in addressing taboo topics without hesitating to speak out on political issues. During her long career she recorded more than 200 songs. Other famous cheikhas include Cheikha Rabia and Cheikha Djenia.

discogs.com

In the 1930s-1950s, Oran's musical landscape underwent extensive transformations. Andalusi, malhun, raï, and ughniyaughniyaUghniya (literally “popular song”) is an Egyptian pop genre that reached its peak in the 1970s. Its main representatives are Umm Kulthum, Mohammed Abd-al-Wahab and Abdel Halim Hafez.—the music of Umm Kulthum and other popular Egyptian artists of the time—were mixed and also influenced by jazz and swing introduced by the Americans during World War II. New instruments appeared in the city such as the trumpet, accordion, piano, violin, and banjo. Combining them with regional types of percussion instruments, Oran musicians created a new genre—wahrani (from the Arabic version of the city's name, Wahran), which was closely related to raï music.

At the same time, guided by the similar logic of combining new instruments with traditional ones, male performers started to transform raï which had been previously performed by female cheikhas only. These new performers ordered lyrics from professional wahrani poets, distinguishing them from the cheikhas who usually created their verses on the spot. In other cases, raï performers borrowed from wahrani music, adding their own lyrics to it. Among the most notable musicians of that period are the trumpeter Messaoud Bellemou, who worked with singers Benfissa and Boutaiba Sghir, and Ahmed Zergui and his band “Les Frères Zergui.”

During the struggle for the independence of Algeria, wahrani and raï performers supported the National Liberation Front, singing nationalist songs as male cheikhs did in the early 20th century. This led some of them to flee the country, while others ended up in prison. Cheikha Rimitti also supported the liberation war by performing songs dedicated to the conflict.

Mohand Anemiche / Odysséo

In 1962, Algeria gained independence and music came under strict control by a new government that was implementing Arab cultural reform. Only Egyptian and patriotic songs were played on the radio along with classical andalusi, which became the national music of the new republic. Raï again began to be seen as unacceptable, as it evoked associations with the colonial past and the lifestyle of cheikhas that was still considered immoral. Moreover, raï performers had already begun criticizing the new government and the authorities did not want to put up with it.

Nevertheless, the genre continued evolving, taking on a modern pop form that targeted a younger audience. It became possible to dance to raï music, to which the performers added saxophone, electric guitar, and other modern instruments. Updating the sound, musicians also updated their image. They began to call themselves “cheb” or “chaba” (for males and females, respectively), which meant “young” and actually corresponded to their age and distinguished them from cheikhs and cheikhas (which literally stood for “old”). It also connected them with their target audience, mostly comprised of the unemployed under the age of twenty five. These young people were disappointedwere disappointedTony Langlois, “The Local and the Global in North African Popular Music.” Popular Music 15.3, 1996. with their position and grew very critical of post-colonial regimes. Thus, raï music started to express the new identity of young Algerians. For example, the song “To Flee, but Where to?” (El Harba Wayn?) by Cheb Khaled became a real anthem of the generation, both in Algeria and among the diaspora in France and other countries where Algerian emigrants clashed with local nationalist groups.

Look see the brave have all become cowards

You don't hear anything but “once upon a time”

They cut into the flesh of man

They drink the blood of their brothers

No life no fear […]

To flee but where?

Tell me oh poor soul

Oh I have cried

Oh I have suffered

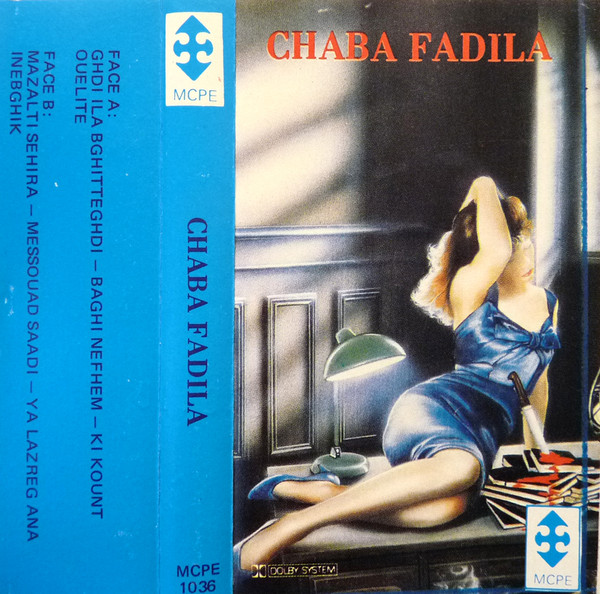

The main stars of the renewed genre were Chaba Fadela and Cheb Khaled, who took turns performing the first real hit of raï pop “Sleep Does Not Become My Face” (Ana Mahlali Noum), after which this music began to move beyond Oran. However, in the early 1970s raï was still bannedwas still bannedDjamel Kelfaoui, Michel Vuillermet "Algérie, Mémoire du Raï", 2001. from the radio and TV in Algeria, remaining underground cabaret music. But after these songs started being broadcast on radio stations in the south of France, it was no longer possible to ignore the influence of raï inside Algeria, forcingforcingMiriam Rosen, "Undertone". Artforum, 1990.

the government to recognize the genre and lift the restrictions.

Bottom: Sheba Khaled's Moule El Kouchi and Fuir, Mais Où? album covers,1980s

discogs.com

In 1985, Oran hosted the first official live state television festival of raï music, during which Cheb Khaled was proclaimed the king of raï. Like Western rock stars, he broke the moral and social norms of his culture: his clothes, videos, lyrics, and music were unacceptable to many Arabs. The public was shockedshockedNasser Al-Taee, "Running with the Rebels." Echo magazine, vol.5, issue 1, 2003. when he appeared on French television with a shopping bag, a tall blonde, or a bottle of wine. In the eyes of traditionalists, he and other raï performers undermined the concept of an ideal Algerian society by addressing social and sexual aspects of everyday life in their songs. The local press often described raï as an imperialist force that was trying to destabilizetrying to destabilizeMarc Schade-Poulsen, “Men and Popular Music in Algeria: The Social Significance of Raï”, 1999.

Algerian society and secularize the second generation of immigrants in France.

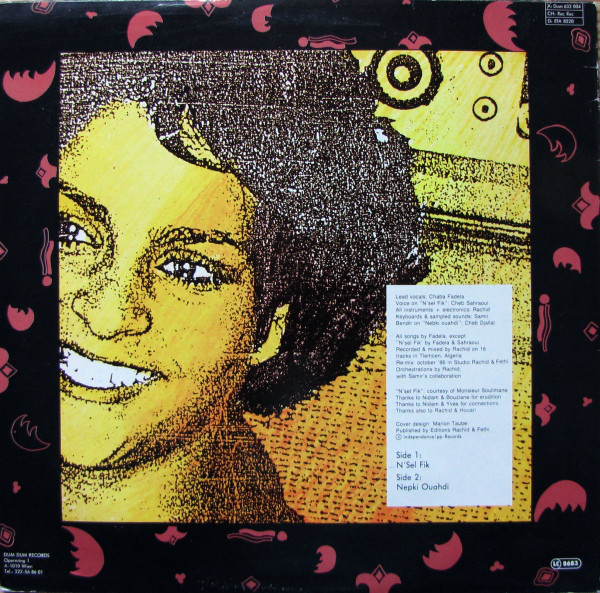

However, back home the raï scene soon had to face a serious blow. After elections held in December 1991, the Islamic Salvation Front won the majority of seats in the Algerian parliament. Its members immediately banned raï again, closed nightclubs, and imposed a penaltyimposed a penaltyRod Skilbeck, “Mixing Pop and Politics: The Role of Raï in Algerian Political Discourse,” 1995. on singers whose lyrics were considered vulgar. Thus, most raï performers had to flee Algeria. In 1994, singer Cheb Hasni who had remained in the country was killed, and in 1995, Rachid Baba Ahmed, a legendary musician and producer who, together with his brother Fethi, had worked with Khaled and other raï stars and made a huge contribution to this genre, was shot in his own record shop in Oran.

Like other raï stars, Cheb Khaled reached international success after moving to France, where in 1992 he released the song “Didi.” It became a mega hit in both France and West Asia, despite being dedicated to unrequited love and its lyrics including a description of his beloved's short skirt. The word “didi” itself did not mean anything in particular, leaving room for interpretations, including indecent ones. This use of words with multiple meanings became a trademark of the genrebecame a trademark of the genreNasser Al-Taee, “Running with the Rebels.” Echo magazine, vol.5, issue 1, 2003., allowing raï performers to bypass censorship.

By the late 1990s, raï had achieved tremendous success in Africa, Asia, and Europe and become one of the largest ethnic music genres in the world. However, the attitude in Algeria remained the same, leading to the launch of the International Festival of Raï Music in the city of Oujda, Morocco which remains the central event for the entire genre to this day. Morocco claimed its rights to raï, appealing to the fact that Oran had once been a part of its territory. In 2013, the king of Morocco granted Khaled Moroccan citizenship, which, however, did not prevent Algeria from applying for the inclusion of raï in the 2016 UNESCO Intangible Heritage List as a genre of uniquely “Algerian Folk Music.”